drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

Dimensions: Sheet: 22 3/8 × 15 5/8 in. (56.9 × 39.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

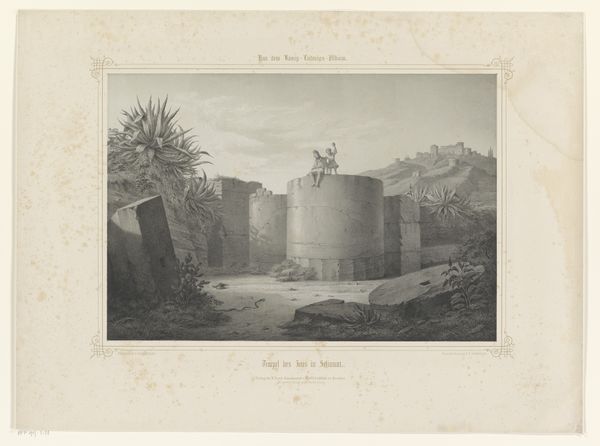

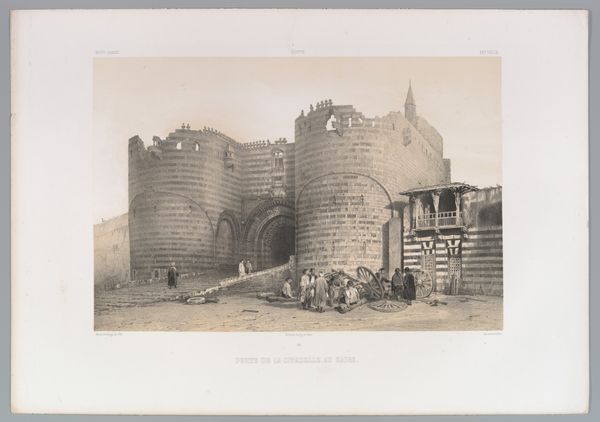

Curator: This is "Château d’Alep" by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, created in 1843. It’s an etching and print on paper. What strikes you about it? Editor: The muted palette creates such a somber atmosphere, almost oppressive. You feel the weight of that structure looming over everything. Curator: De Prangey's Orientalist perspective definitely colors this piece. We must consider the historical context of European fascination with the "East." What does it mean to depict Aleppo through this lens, especially in 1843, during a period of intense colonial interest? Editor: And this printmaking technique, etching, is labor-intensive and demands skill. It wasn’t about mass production, but carefully controlled output and distribution, mostly targeting Europe’s privileged classes interested in acquiring depictions of exotic lands and monuments like these. Curator: Right. Consider how identity and power are intertwined. This wasn’t merely capturing a landscape. It was constructing a narrative, one that often reinforced existing power structures. What does it signify to portray this site? Who is telling the story, and whose stories are left untold? How does this impact our current interpretations? Editor: The very act of translating Aleppo into a consumable object for a European audience is interesting. It turns architecture and social space into merchandise through a matrix of materials and artistic process that requires examination. What kind of papers were utilized and where did those resources come from? What socioeconomic access does this medium afford, both for its producer and consumer? Curator: And furthermore, how does the Romantic style influence this construction? The emphasis on the sublime, the exotic, often romanticized the subject while simultaneously obscuring the lived realities of the people within these landscapes. Editor: Absolutely. You’ve laid bare the sociopolitical mechanisms within Orientalism’s commercial and artistic framework. Thinking about how materials, means of production, and dissemination all contributed in perpetuating a very specific cultural vision. I hadn’t quite conceptualized this intersection so critically. Curator: This etching encourages us to question not just what we see, but also how and why we see it this way. Art like this challenges us to delve into deeper ethical and political considerations. Editor: This exercise reinforces my commitment to critically examine production and reception in the study of cultural heritage. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.