Dimensions: height 435 mm, width 590 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

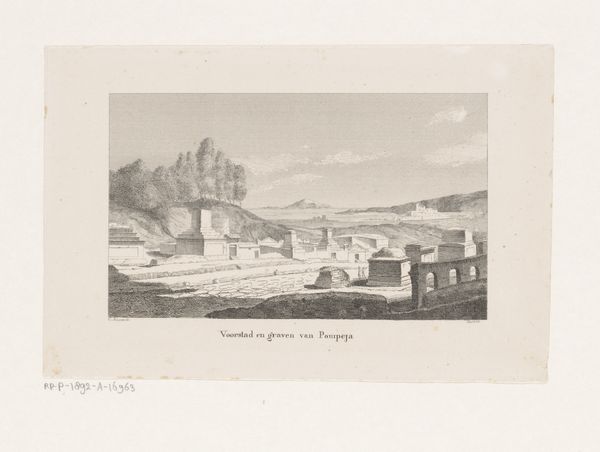

Editor: This print, "Ruins of a Temple at Selinunte," dates from the 1850s and is by Gustav Seeberger. It's an engraving...The detail is amazing, especially considering it’s a print. What really strikes me is how small the figures on the ruin appear compared to the overall structure. What do you see in this piece? Curator: It's fascinating to consider the socio-economic context in which this print was created. Engravings like these were often made to disseminate knowledge about classical architecture and history, catering to a growing bourgeois class interested in self-improvement and cultural capital. The production of such prints involved skilled laborers – engravers, printers – whose work was often unacknowledged, hidden behind the artist’s name. Think about the materiality of this print too – the paper, the ink, the metal plate used for engraving. Each element speaks to a network of production and consumption. Do you think Seeberger visited the ruins himself? Editor: That's a great question; I'm not sure. I was so caught up in the artistry I hadn't thought about all the labor involved! But now that you mention it, how does this compare to, say, the work of a stonemason back when the temple was originally built? Are we meant to view these two as equal creative contributions in their own way? Curator: Precisely! It invites us to reconsider our definition of "art" and the hierarchies we often impose. Both are acts of skilled labor shaped by particular tools, materials, and socio-economic conditions. The stonemason, however, might have had a deeper cultural connection, fulfilling a specific purpose in their community. Seeberger, on the other hand, produced a commodity for a market, fueling a colonial gaze. What do you make of the way he romanticizes this image? Editor: I never thought of landscape prints as commodities before. That changes my perspective entirely! Thanks so much! Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about the labor, materiality, and historical context truly opens up a deeper understanding of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.