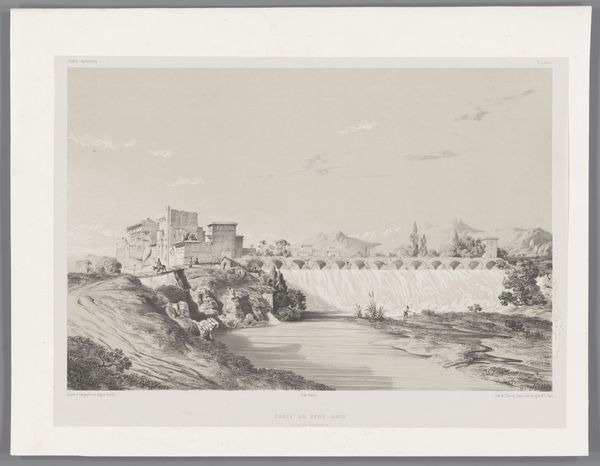

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

orientalism

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 434 mm, width 588 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

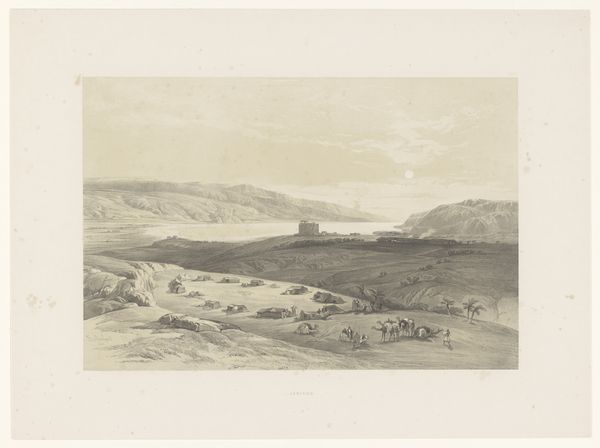

Curator: This print is titled "Mamasani toren," crafted between 1843 and 1854 by Eugène Flandin, and preserved here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is its incredible sense of scale. The landscape sprawls, but the delicate lines of the engraving keep it incredibly detailed and precise. It has a very formal, almost documentarian feel. Curator: That formality stems from its purpose, I think. Flandin was part of a French diplomatic mission to Persia. His engravings were intended to document the architecture, landscapes, and people he encountered, contributing to the Western understanding, or perhaps *misunderstanding*, of the region. Editor: I'm intrigued by the choice of engraving as a medium for this kind of visual reporting. The process is so labor-intensive. The subtle gradations of light and shadow must have taken hours to render onto the metal plate. Think about the manual skill, the careful control over each line… Curator: Precisely, and it underscores a specific power dynamic, doesn’t it? A European artist deploying a painstaking technique to capture, and therefore, in a way, possess, this "Oriental" landscape for a European audience. There's a certain ethnographic lens at play, fueled by colonial desires. Editor: Yet, that "possessive" act also preserved aspects of Mamasani life we might not otherwise know so well. The textures of the buildings, the clothing of the figures, the vastness of the mountains—the materials of a place carefully represented and transformed into an exportable artifact. There is the immediate political context and also the lasting, intricate material record. Curator: It certainly raises complex questions about representation and artistic agency. The level of detail invites us to examine how the artist both documented and interpreted his subject, within the larger framework of orientalism, which really cemented existing biases at the time through popularized imagery. Editor: I agree. Seeing the world meticulously carved into metal pushes us to remember the hand and the culture of the artist making it. That adds another layer to how we interpret that represented world now. Curator: I think that understanding its place in the visual and political landscape of the time allows us a richer, more informed reading of it today. Editor: A delicate tension, seeing it, and seeing it within the network of labor and context it both sprung from and then further shaped.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.