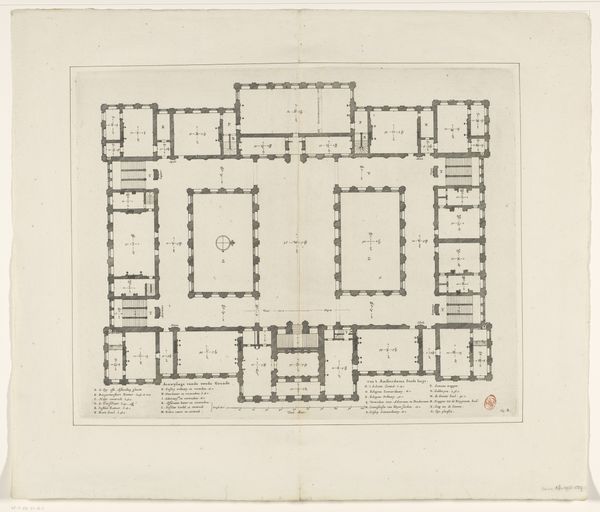

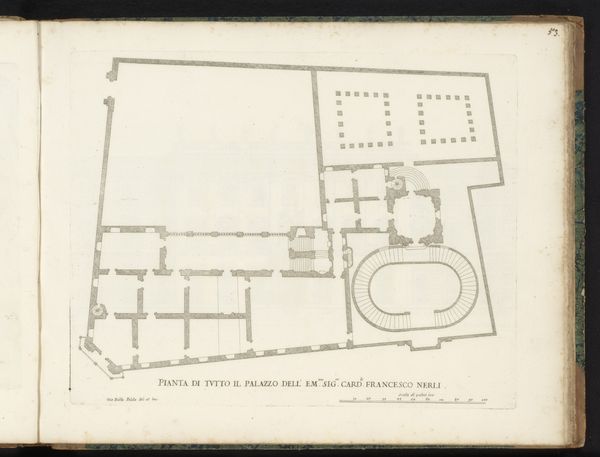

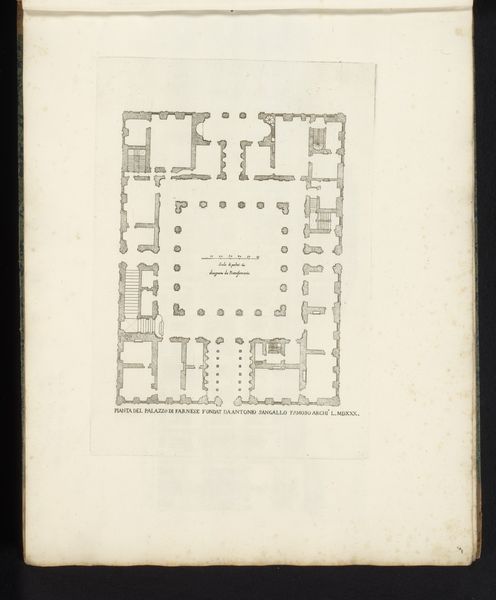

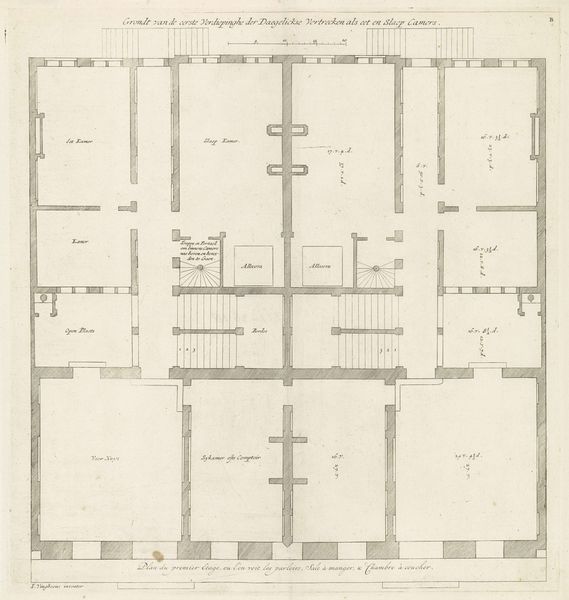

Plattegrond van de begane grond ('eerste of onderste Grondt') van het Stadhuis op de Dam 1661

0:00

0:00

danckerdanckerts

Rijksmuseum

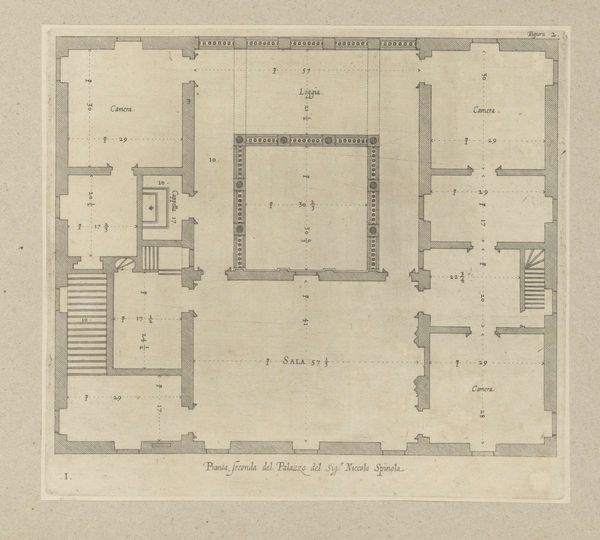

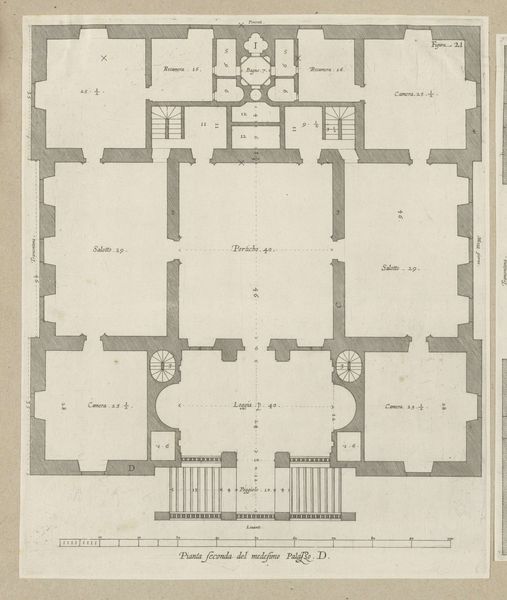

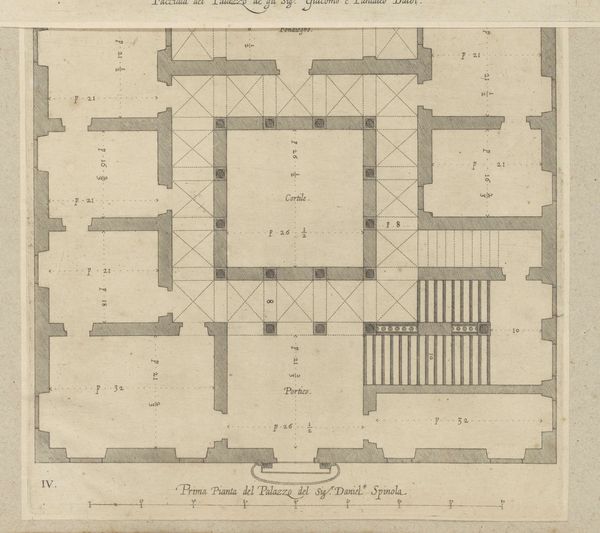

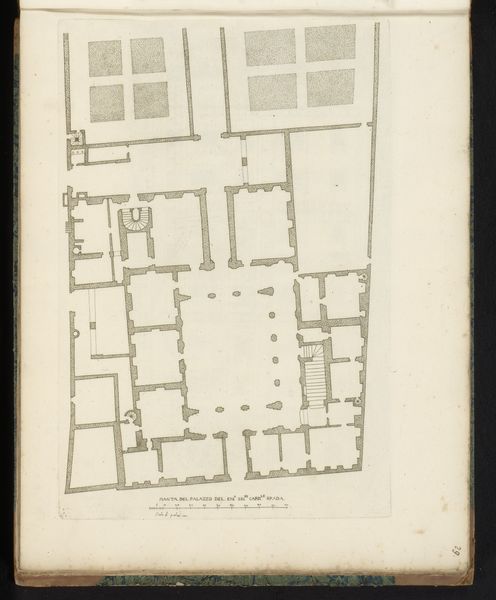

drawing, architecture

#

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

baroque

#

architectural plan

#

geometric

#

elevation plan

#

architectural section drawing

#

architectural drawing

#

warm-toned

#

line

#

architecture drawing

#

architectural proposal

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 401 mm, width 520 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Dancker Danckerts' "Plattegrond van de begane grond" from 1661, a drawing depicting the floor plan of what I believe is a city hall. The level of detail is quite remarkable; you can practically trace the routes of people moving through the space. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This drawing, rendered on what looks to be handmade paper, invites us to consider the labor involved in its creation, and furthermore, the labor it represents. Look closely; what purpose did this elaborate design serve? Was it purely functional, or did the detailed representation itself hold value? Editor: I suppose the very act of meticulously mapping out a space reflects an ambition for control over it, maybe even a projection of power. Curator: Precisely! And how might the materiality—the ink, the paper, the drawing tools—relate to the social status of those commissioning and creating such a detailed plan? Consider the accessibility of these materials during that time. Were they readily available to everyone? Editor: Certainly not. The materials alone would signify wealth and status. So, creating something like this was both a practical exercise and a display of resources. The building materials themselves are absent here, but implicated through this very architectural projection. Curator: Yes, and thinking about the intended audience adds another layer. Was this plan meant for public consumption, perhaps influencing civic pride? Or was it a restricted document, circulated among a select elite who had direct economic ties to this municipal structure? Editor: That's a fascinating point. I hadn't considered the drawing's circulation as part of its meaning. So it’s less about just *what* it depicts, and more about *who* had access to this depiction and *how* they might have used it. Curator: Exactly. Examining the process, materials, and the social context of both its making and reception opens up avenues beyond simply admiring its aesthetic qualities. I wonder, does viewing the built form from this perspective challenge how you appreciate it now? Editor: Definitely. I'll now look at architectural drawings with fresh eyes. Thinking about access and resources complicates a seemingly straightforward depiction. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.