print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 79 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

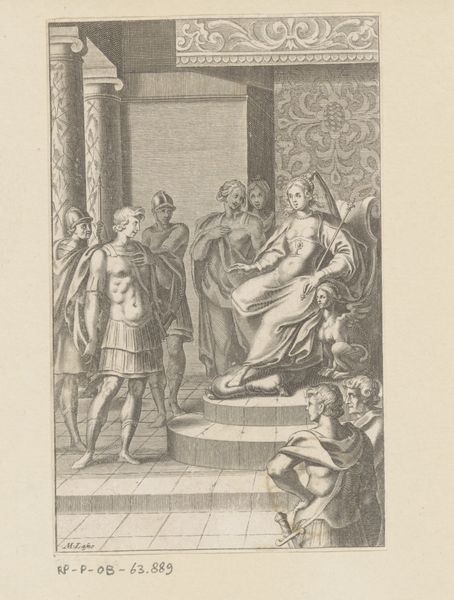

Curator: Today we are looking at “Weldaad”, an engraving by Enea Vico, created sometime between 1533 and 1567. It’s currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The texture is remarkable! Looking closely, I am drawn to the detailed rendering of fabric and chain links, a palpable sense of material weight conveyed through line and shadow. Curator: Vico masterfully uses engraving to represent the social hierarchy of the time. The central figure, enthroned and adorned with elaborate clothing, literally looks down on the kneeling man. Chains bind him. It begs questions of agency, of class struggle, and who benefits, really, from supposed 'charity'. Editor: Absolutely. Consider the physical labor involved in both creating the print and being enslaved. The engraver painstakingly creates a matrix from which multiples can be made and circulated; likewise, the enslaved exist only to fulfill someone else's objectives through manual labor. And consider also the economic relationships embedded within that hierarchy—who benefits materially from the subject's subservience? Curator: Indeed. This image can serve as a potent critique of power dynamics that are always at play, a meditation on intersectional domination. I’m struck by how it can be linked to modern discourse surrounding systemic injustices. Editor: Exactly. And in Vico’s process of production – a matrix being impressed on paper -- what are we to make of its seeming disposability, as print becomes the substrate for something else to be done? It seems analogous to this captured individual, no? Both reduced and primed only to satisfy the intentions of another. Curator: Perhaps. And on a symbolic level, even the dog at the throne looks to be looking downward, as if reinforcing societal structures are not merely about force but compliance. How far are these structures internalised, by the privileged but equally by the downtrodden? What implications might it carry for future, radical transformation? Editor: Such layered reflections show this is more than a mere display of an older world order, but a pointed meditation on the social construction of "weldaad" itself, which continues to bear relevance. Curator: It encourages us to question the inherent power dynamics within benefaction itself, reminding us of its lasting implications in contemporary social exchanges. Editor: A superb example, therefore, of how printmaking is never really only printmaking; here it seems the substrate itself to social formation and thought, still ripe with challenge today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.