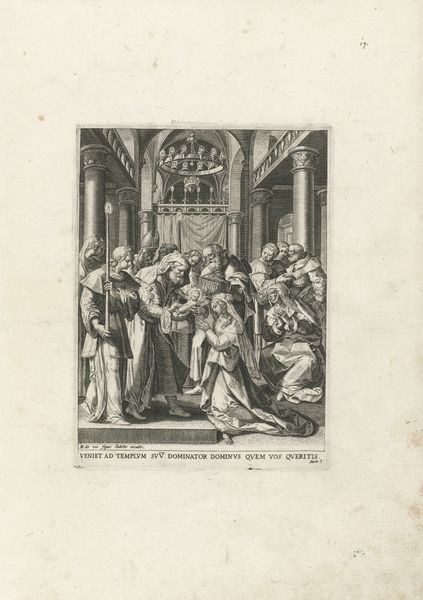

print, etching, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 205 mm, width 250 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this detailed print, "Elia wedijvert met de Baälpriesters," produced after 1567 by Philips Galle, my eye is immediately drawn to the chaos. It feels crowded, theatrical. Editor: The density of figures really heightens the drama, doesn't it? The engraving technique used here gives incredible detail. And how those lines are deployed to suggest shadow—remarkable. Tell me more about the history this piece illustrates. Curator: This work captures the biblical narrative of Elijah challenging the priests of Baal. Galle positions Elijah here at the forefront. Behind him, a tense, densely packed crowd hints at the social upheaval at play in the story. Editor: And you see that contrast sharply even formally. Look at the positioning: Elijah, almost pleading, framed against that statue atop the plinth, so cold and rigidly posed. Curator: Indeed! It’s a visual reinforcement of the power dynamics. This scene isn't just about faith; it’s about competing for societal dominance and theological supremacy during a turbulent period of religious reformation across Europe. Editor: It's interesting to consider the impact of the Mannerist style in this religious context. The elongated figures, the almost claustrophobic composition - it heightens the sense of unease and instability. It’s not just about portraying a historical event, it's about provoking an emotional response. Curator: Exactly. Galle understands that the power of an image lies in its ability to stir its audience. The exaggerated gestures, those anxious faces within the throng - it all builds to a crescendo of both visual and ideological tension, intended to rally support. Editor: The material itself adds a layer too—printmaking democratized imagery, making it far more accessible. Religious imagery took on new meanings when it became widely distributed and consumed, right? Curator: Absolutely. Prints like this were vital tools. They carried powerful religious and political messages far beyond the elite circles of the church or the wealthy patrons. Editor: Reflecting on the technique and the narrative, the power of a print lies in the balance of aesthetic quality and cultural relevance. It makes us question what it meant for Galle, as an artist in that particular historical period, to represent religious and societal conflicts through print. Curator: A pertinent question, and one that this engraving so vividly provokes. It gives us so much to consider about both faith and art’s powerful place in society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.