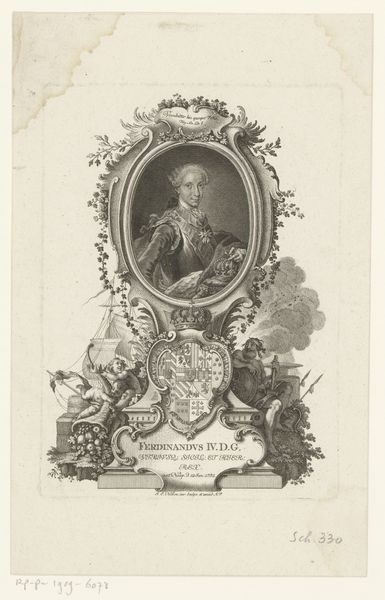

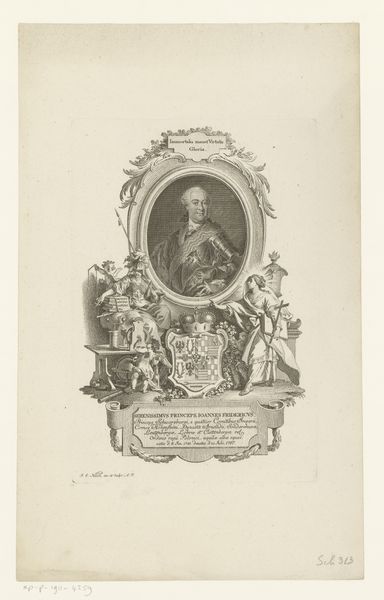

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this is Johann Esaias Nilson's "Portrait of Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress," made sometime between 1740 and 1788. It’s an engraving, so a print. It strikes me as intensely decorative, almost over the top. What stands out to you about it? Curator: What I notice is how the very means of producing this image—the engraving technique—dictates its meaning and accessibility. Consider the labor involved in creating such detailed ornamentation and portraiture. This wasn't just about representation; it was a calculated performance of power through accessible imagery. Editor: A performance of power? How so? Curator: Think about printmaking's role in disseminating images. This engraving allowed Maria Theresa’s likeness and the visual trappings of her power to circulate widely, far beyond the court. The *material* itself became a tool of political projection, a carefully managed brand, if you will. Consider how it would have been distributed. Was it primarily consumed by the aristocracy or could common people obtain it as well? Editor: That makes a lot of sense. I hadn't really thought about it in terms of mass production, even then. So, by focusing on the 'stuff' of the artwork - the engraving, the paper - we understand more about how power was visualized and consumed. Curator: Precisely. And this also challenges a purely aesthetic reading, forcing us to consider how the artistic labor itself and access to it shapes our understanding of the subject, Maria Theresa. Editor: That's a completely different way of looking at it for me. Thanks, I will never look at prints the same way. Curator: Indeed, sometimes focusing on production, materiality and its circulation provides very revealing and challenging insights into artistic practice.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.