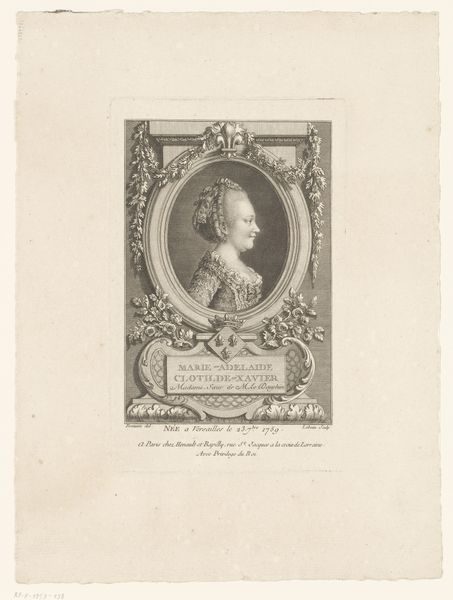

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, yes, here we have Johann Esaias Nilson’s 1771 engraving, “Portret van Marie Antoinette als dauphine,” which, as you know, is Dutch for "Portrait of Marie Antoinette as Dauphine." It's part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: It's quite striking, in a very mannered way. The young Marie Antoinette seems almost encased in this elaborate frame, a bit like a doll. I notice the line work immediately—so delicate yet precise. What was the typical printmaking process back then? Curator: The engraving is a dance of symbolism, as you can see. The cherubs, the floral garlands, the architectural details—they all contribute to the visual language of power and grace. The oval frame itself reinforces the idea of her as an object of beauty, set apart. Editor: Objectification is key, isn’t it? Considering it’s an engraving, made through a painstaking process of carving into a metal plate, it points to labor but also control of image dissemination. How were these prints usually distributed—were they widely accessible? Curator: Relatively speaking, yes. Prints like these were a crucial way to disseminate images of the royal family, shaping public perception. They served almost as proto-publicity shots, reinforcing the monarchy’s image through visual repetition and strategic deployment of symbolic elements. Editor: And what about the intended audience? Did they have access to images of her before, or would they mainly hear word-of-mouth about her reputation? The details would almost create the perception that Marie Antoinette embodies luxury... Curator: Very perceptive. Most people in the population wouldn't have ever encountered royalty firsthand. They depended on imagery and secondhand storytelling. The engraving idealizes Marie Antoinette, of course, portraying her not just as royalty, but as an icon, reinforcing a perception, perhaps even an aspirational model. Editor: Looking closer at the material itself gives it such interesting connotations, as a relatively mass-producible portrait created so painstakingly. A contrast to its own inherent symbolism, creating a dialogue about how power is consumed, even from the working class who made them. Curator: Yes, indeed. In this context, it's both an aesthetic object and a tool for cementing a royal persona. A visual artifact speaking to us about ambition and aspiration but also to consumption in 1771, no less. Editor: Absolutely. Makes you consider how meticulously planned these historical images must have been. A tiny keyhole through which we see larger ideas!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.