drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 15/16 × 11 13/16 in. (25.2 × 30 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

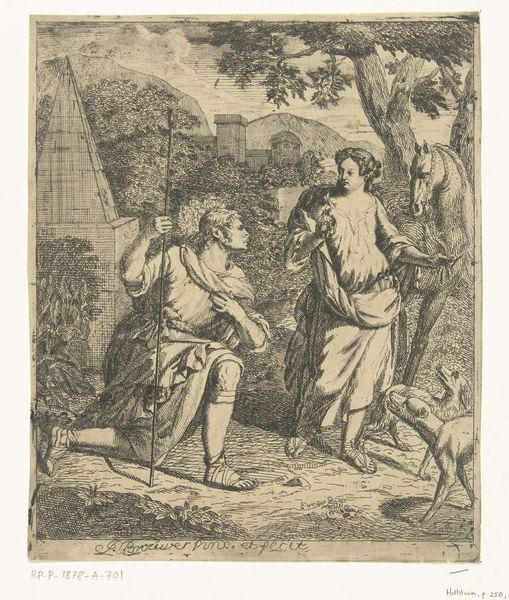

Editor: Here we have Simone Cantarini's "Mercury and Argus", made between 1625 and 1635 using etching, engraving, and drypoint. The figures have such interesting definition for prints, they feel almost sculptural. How would you approach looking at this work? Curator: Considering its materiality, I'm immediately drawn to the labour involved in its production. Look closely at the lines; the varying thickness achievable through etching and engraving suggests a nuanced control of the burin and acid. Do you see how this intricate detail highlights the engraver’s skill, almost as a performance of technical virtuosity, while illustrating a classical narrative? Editor: Yes, it’s clear the artist had significant control of their tools. Given that prints would often be reproduced, does this mean Cantarini was perhaps thinking about the value of production or the consumption of images during his time? Curator: Precisely! The multiple processes --etching, engraving, drypoint-- speak to experimentation within printmaking at the time. Think about the intended audience. Were these images for wealthy collectors, aspiring artists who wanted to copy them, or circulated more broadly, thereby democratizing access to classical narratives, perhaps for pedagogical reasons? This impacts how we understand Cantarini's choices regarding style and technique. How do these techniques inform its narrative elements? Editor: The linear quality almost flattens the image, and feels more about line than tonal range. Mercury’s deception, told through his flute music lulling Argus to sleep before killing him, almost takes a back seat. Cantarini prioritizes displaying his skill as a printmaker above pure storytelling? Curator: That's insightful. Rather than solely focusing on the mythological content, we see Cantarini engaging with and mastering his craft, highlighting the material transformation from concept to printed image and its circulation in seventeenth-century society. Editor: I see. The tools and techniques themselves become the message! Thank you for pointing that out; it gives a new meaning to what I originally thought of as just a striking image. Curator: Indeed! Approaching art through the lens of production reveals hidden layers of meaning that traditional art historical analysis might overlook.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.