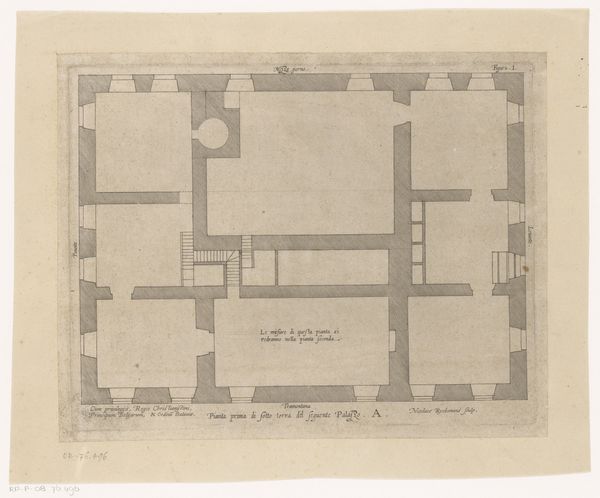

Dimensions: height 234 mm, width 356 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

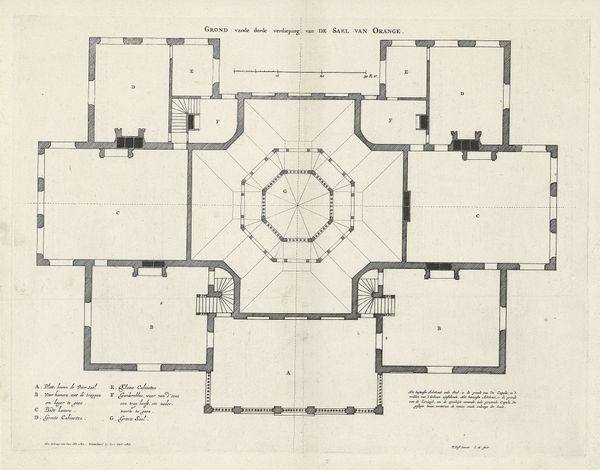

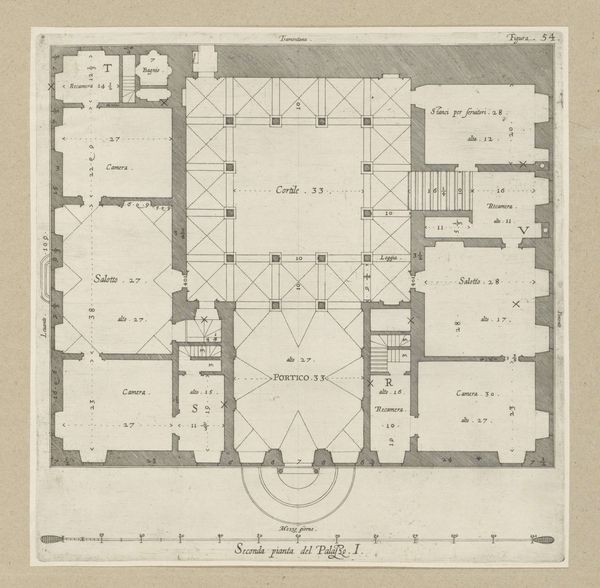

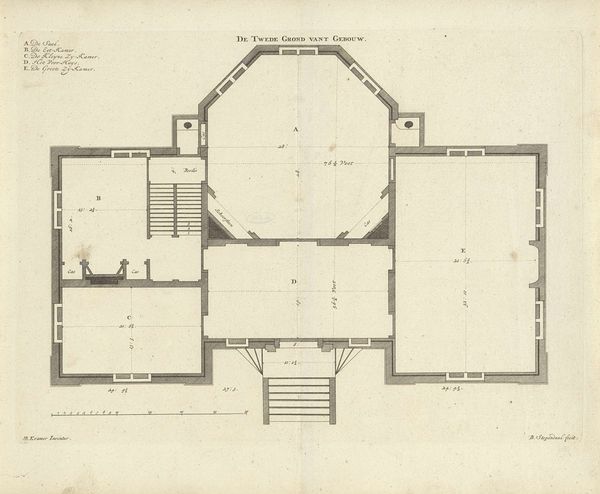

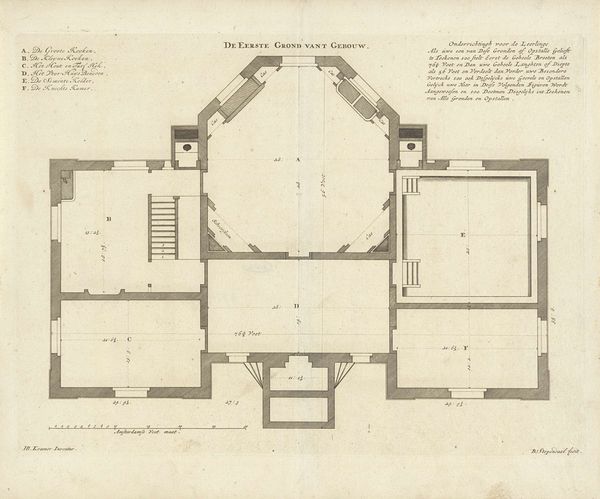

Editor: Here we have Carl Albert von Lespilliez’s “Plattegrond van kelder,” or “Ground plan of a cellar,” from 1745. It's an engraving, a drawing of geometric forms outlining an architectural space. What immediately strikes me is its functional aspect; it's less a piece of art and more a set of instructions, yet it’s undeniably beautiful in its precision. What do you see in it? Curator: I see a map of social relations embedded in the very stones of this cellar. The engraving, the lines themselves, represent not just architecture, but the meticulous planning and labor required to construct such a space. Consider the materials sourced, the tools used, the division of labor—from quarrymen to draftsmen—all contributing to this "functional" aesthetic you mentioned. Editor: That’s interesting. So you're saying it's more than just a plan, it's a record of the labor that created it? Curator: Precisely. Look at the clear, almost obsessive, rendering of space. This isn't just about storing wine or food. This is about projecting power, control over resources. The materials themselves—stone, presumably—speak of permanence and wealth. Think about who had access to these cellars, who built them, and who benefited from their existence. Editor: It does make you wonder about the hands that shaped this space. Was this a common practice, to create such detailed plans? Curator: Architectural drawings like this reflect a shift in how spaces were conceived and constructed, towards rationalization and control, aligning perfectly with emerging capitalist modes of production. The engraving itself facilitated the mass distribution of such designs, influencing building practices on a wider scale. Editor: I never considered that a simple blueprint could be so deeply connected to labor and societal power dynamics. Curator: It's a reminder that even the most seemingly practical objects are products of specific social and economic forces. Looking at the material processes, and thinking of it more broadly, can reshape our entire understanding of art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.