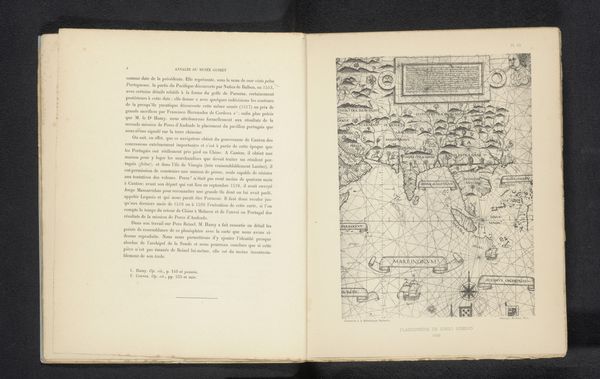

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 385 mm, width 530 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

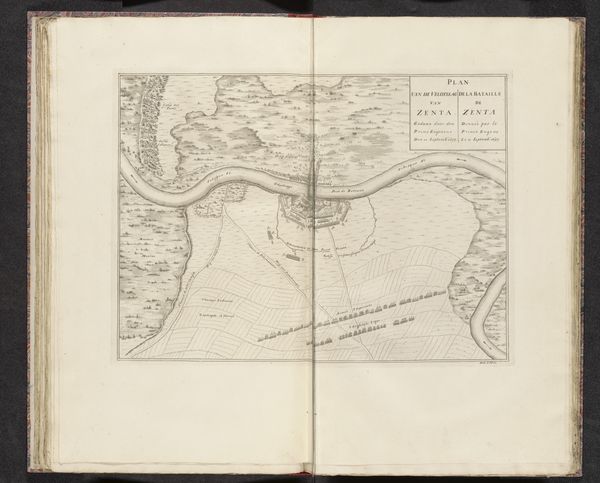

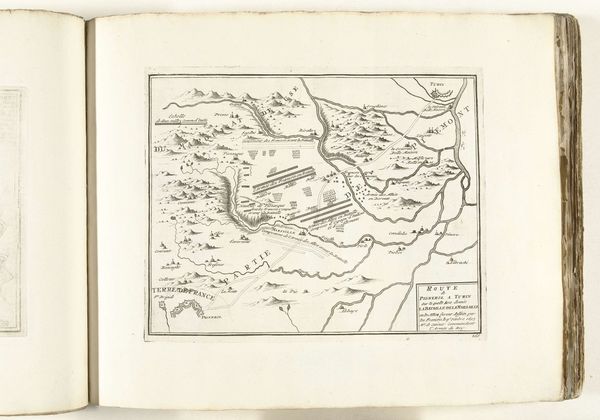

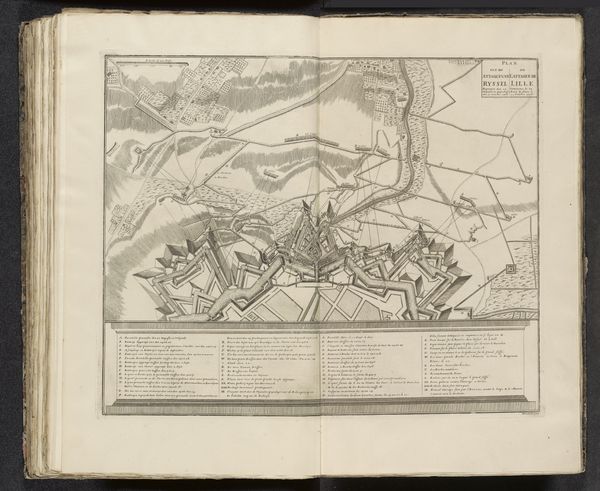

Curator: This engraving, dating from between 1693 and 1729, depicts a “Kaart van de slag bij Marsaglia, 1693” - or a Map of the Battle of Marsaglia. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: At first glance, it feels quite sterile, doesn't it? All these lines and carefully placed symbols... almost like an architect's plan rather than a scene of conflict. Curator: That's a fascinating point. Consider how war was represented then, versus now. The “battle map” evolved into a way to lay claim to political territory. It was a means of documenting conquest, but it was equally deployed to consolidate classist, heteronormative assumptions that justified this conquering. Editor: So, it’s not just a factual account, but an instrument of power? Thinking about these topographic maps from an iconographic perspective, there’s this sense of laying claim. Borders dictate who is in, who is out. What are the enduring symbols you see here? Curator: I think it hinges on the notion of controlled perspective. Every element seems meticulously placed, but each decision is loaded, reflecting a worldview rooted in dominance and the assertion of control. I'd question the very assumption of neutrality within its design. Editor: Exactly! There are these recurring triangular shapes to suggest mountain ranges—timeless symbols of challenge or obstacles—yet neatly ordered on the page. There’s a conscious desire to translate chaotic, complex human struggles into manageable visuals that enforce a supposed “rational” order. Curator: And it extends beyond simple geographical representation. Each troop movement, marked fort—it all coalesces into a visualized social structure… a military class system etched onto the landscape itself, with real impact on gender and racial hierarchies of the time. It speaks to our current landscape of late capitalism and its inherent biases that perpetuate injustice and exclusion, doesn’t it? Editor: You're right, it’s striking how these supposedly objective records have always encoded certain biases. Even seemingly mundane marks of terrain were invested with culturally specific associations of that time period that are worth unpacking. Curator: Indeed. Thinking about it in our contemporary terms, perhaps seeing the ways in which biases have been historically institutionalized enables us to re-evaluate present ones, or to better fight them. Editor: Absolutely. It serves as a potent reminder that maps, like all images, carry cultural memory and that visual elements evolve to become instruments for larger systems of belief.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.