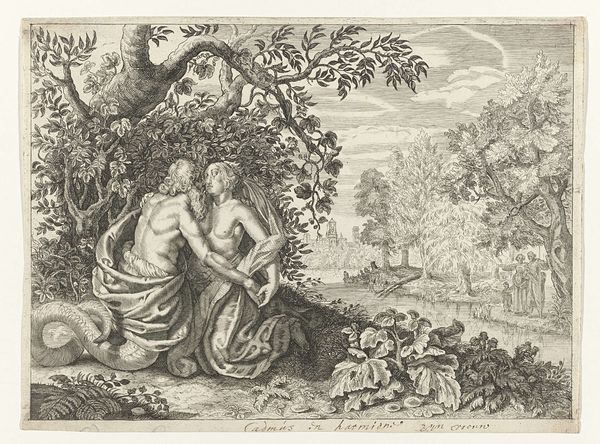

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 224 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This detailed engraving by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger, likely created between 1636 and 1670, depicts Nessus carrying Deianira across the river. The work is titled "Nessus zet Deïanira de rivier over", now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is how unsettling the scene feels. The frantic energy of Nessus contrasted with the stoic, almost resigned, expression on Deianira's face. And the detail is just astounding. Curator: Absolutely. The line work really emphasizes the drama, wouldn't you agree? The way van de Passe captures the textures - the Centaur's fur, the smooth skin of Deianira – it almost feels tactile. But this piece holds darker undertones when we consider the broader mythos of toxic masculinity and violation within this narrative. Nessus wasn't simply helping Deianira cross the river; he attempted to kidnap her, which resulted in his death by her husband Heracles, yet his final vengeful act against the hero would prove fatal to him. Editor: Precisely. There’s this uncomfortable tension, like a loaded spring waiting to be released. Thinking about the female form portrayed, how are we as a modern audience supposed to engage? The male gaze here, but also an incredibly tragic, iconic symbol of betrayed trust. Curator: A betrayal deeply rooted in societal power dynamics, making Deianira a figure through whom to address how patriarchal narratives historically shaped female victimhood, where they rarely enjoyed personal agency or justice. How much is intentional here, versus convention? Is van de Passe consciously critiquing or simply reiterating these stories? Editor: A knotty question for sure! Either way, revisiting these myths, particularly in light of our current understanding of consent and power, really makes us look critically at their origins and continued presence in our art. It's never *just* a historical piece, is it? It's also always a commentary on now. Curator: I think so too, in many ways it encourages critical engagement and contemplation through narrative reinterpretations, shedding new light on ingrained norms to envision potentially subversive approaches moving forward. Editor: Exactly, turning an antiquated image into a living dialogue is probably art's best magic trick of all.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.