drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain

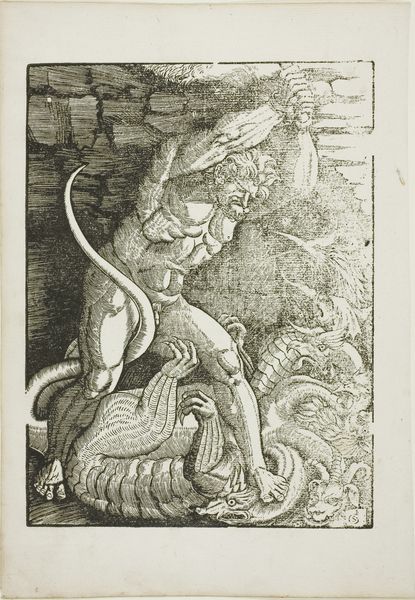

Editor: This is "Trophy," an engraving made by Master FG sometime between 1520 and 1580. It's got this almost eerie, ornamental feel, layering symbols atop a sculpted torso. I'm curious, what’s your take on the layers and material representation in this image? Curator: Let's consider the means of production here. Engraving, a meticulous, labor-intensive process. Each line etched represents hours of skilled labor, reflecting a specific system of production and the engraver's access to materials and training. Notice the details. The artist wasn't simply representing a "trophy," they were *making* a trophy, with lines of ink on paper emulating metallic objects. What's interesting is how the artwork blurs the boundaries between high art and craft through its very method of creation. Editor: That's a good point. I didn’t really consider the blurring between art and craft. What about the combination of imagery—the weapons, the sculpted body, and the mythical creatures above? What are they trying to represent? Curator: Think about the social context and consumption of these images. Prints like this were often part of larger systems of dissemination of ideas and visual motifs. It all points to a circulation of power and status. Each symbol, be it the weaponry or the sculpted body, speaks to this era's focus on classical learning, strength, and artistic mastery. Consider its *function*: likely, it was meant to be circulated, consumed, and possibly emulated. Does understanding its production change your view of its content? Editor: It really does. Looking at the actual work that goes into creating the image makes it less of an image of grandeur, and more like a very labor intensive commentary on grandeur. Thank you! Curator: Indeed, focusing on the process illuminates its deeper meaning, doesn't it? Seeing how these elements are constructed offers a richer appreciation of both art and labor in the Renaissance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.