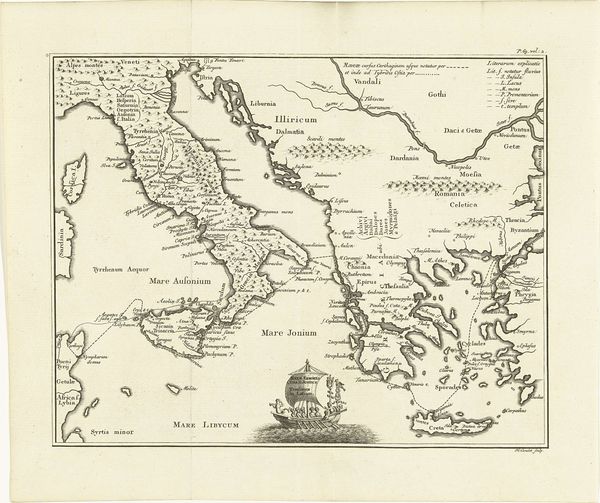

Dimensions: height 496 mm, width 629 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

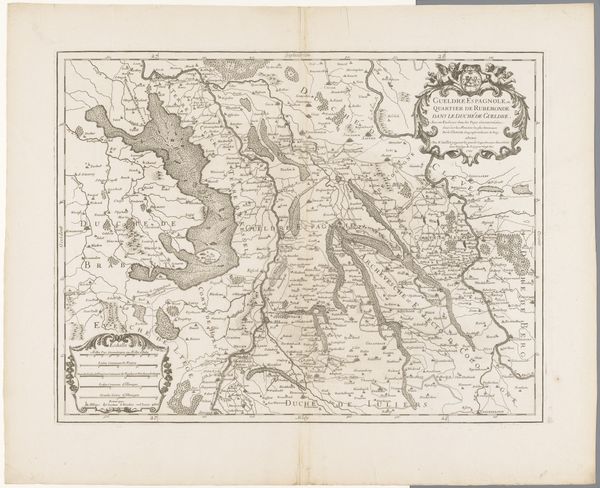

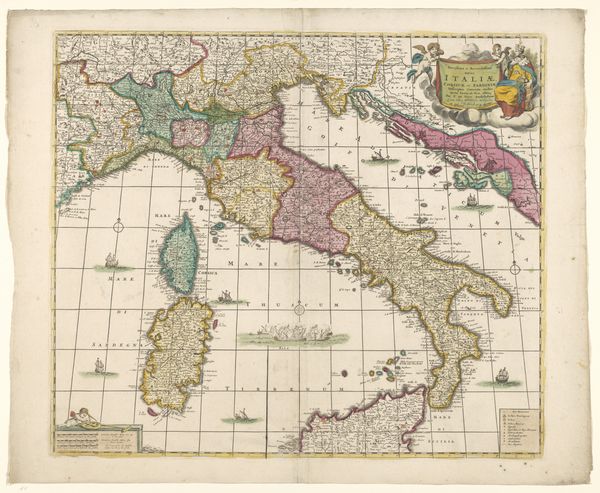

Curator: Let's turn our attention now to a detailed etching entitled "Kaart van Italië in de Romeinse tijd," or "Map of Italy in Roman Times." It's attributed to Johannes Condet, created sometime between 1721 and 1774. Editor: My first impression is how intricately patterned the composition appears. A close look shows endless topographic information meticulously drawn on an apparently untouched sheet of paper. A world depicted with such intentional design invites decoding. Curator: Precisely. Consider how cartography in this period intertwines political agendas with burgeoning scientific accuracy. Italy, depicted here in its Roman iteration, is being mapped both geographically and ideologically. What's shown—and what’s omitted—tells a complex story. How does this affect our understanding of place and territory today? Editor: The way this rendering presents “Italy” raises many critical questions, namely around notions of Italian national identity which, of course, didn't exist as such during Roman times. In effect, cartographers from the Dutch Golden Age and early Enlightenment retroactively imposed a unifying, almost idealized, vision onto a period defined by constant territorial negotiation and violent expansion. Doesn't this contribute to shaping how we engage with this historical subject matter? Curator: That’s very insightful. The stark contrasts and sharp delineations, aesthetically pleasing as they might be, function to categorize and compartmentalize a space with inherently porous, evolving borders. Think of the conceptual framework behind it. Italy isn't simply a geographic area. The artist emphasizes specific locales, possibly to invoke historical or symbolic value of power. It’s visual rhetoric designed to legitimize certain viewpoints and reinforce dominance. Editor: Agreed. What about the impact on us now? This etching, viewed from a modern vantage point, reflects an inherited tendency to streamline or reduce complex histories for seemingly rational or aesthetic effect, a concept worthy of reflection. Curator: Yes. To see an early version of political boundaries presented in artistic and cartographic terms raises crucial concerns. We gain much when critically questioning how lines and territories were constructed then and still persist now. Editor: Thanks to this analytical journey through Condet's visualization, perhaps our visitors feel empowered to critically question visual representations of places and communities and what they do to establish, or dismantle, cultural perceptions of identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.