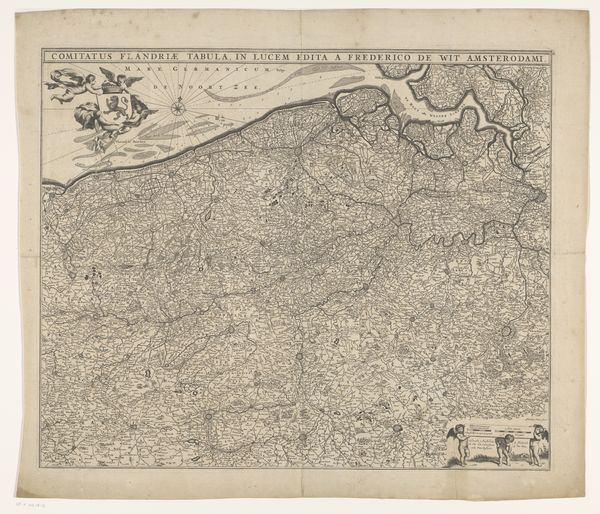

print, etching

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 509 mm, width 603 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

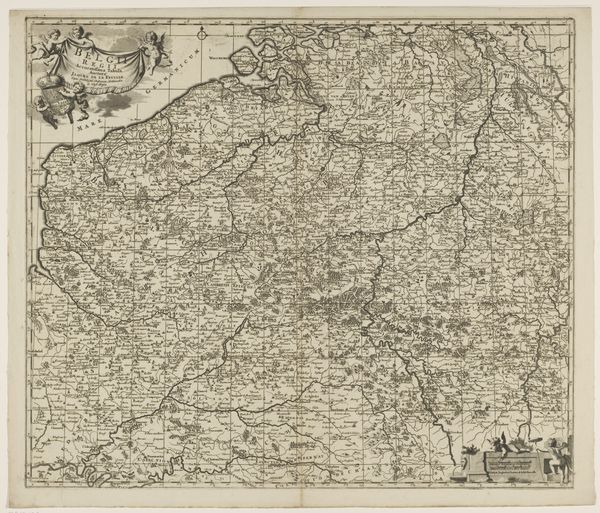

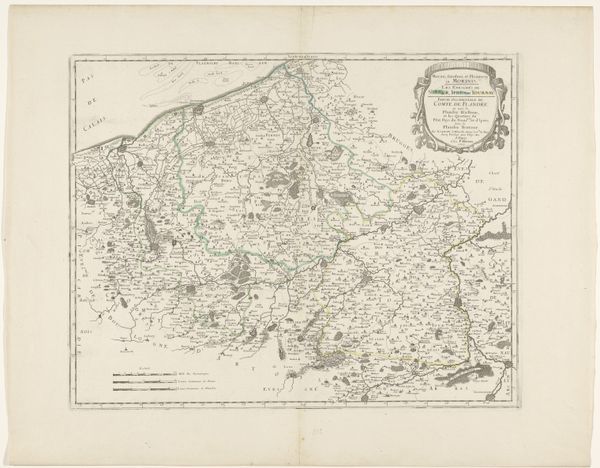

Curator: At first glance, it looks like an intricate spiderweb; a dense and detailed network meticulously drawn. There's something almost overwhelming in the sheer amount of information packed onto this single sheet. Editor: Indeed. What you are observing is an early 18th-century print, sometime between 1707 and 1719, of a map— "Kaart van het graafschap Vlaanderen", or "Map of the County of Flanders." This anonymous work is an etching currently held in the Rijksmuseum. The baroque style is evident. Curator: The visual language of the baroque certainly amplifies its power. And I appreciate that the etching is a reproduction of something existing—a literal attempt to dominate a portion of our known world via this detailed survey. Who gets to decide how space is defined or whose story gets inscribed onto such a public document? The figures in the corner—the reclining goddess, I presume?—what is she meant to convey? Editor: Mapping, in the 18th century, was deeply intertwined with power—military, economic, and political power. Detailed, accurate maps allowed for better navigation, resource exploitation, and military strategy. This is not a neutral representation; the inclusion of those figures aims to evoke a sense of classical authority and legitimacy of the County of Flanders and its rulers. They signify abundance and prosperity – likely used to promote its image to other political powers. Curator: So the landscape, rendered in such exquisite detail, becomes not just terrain, but also a stage upon which power dynamics are enacted, a visual manifestation of colonialism itself. Every city marked, every border defined, representing specific sociopolitical values projected upon land and populace. Editor: Precisely. Maps also served an important symbolic purpose—reinforcing a sense of shared identity and territorial unity within Flanders. Viewing this now allows us insight into 18th-century power structures as cartography intersected with governance. The meticulous detail elevates a survey document to political propaganda. Curator: Absolutely. Today, it offers space to analyze and dismantle the ideological forces at play through its creation, dissemination, and eventual archiving in spaces such as the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The complexities ingrained in an etching meant to serve practical and symbolic purposes—intriguing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.