print, paper, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

#

ink paper printed

#

parchment

# print

#

light coloured

#

paper

#

geometric

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

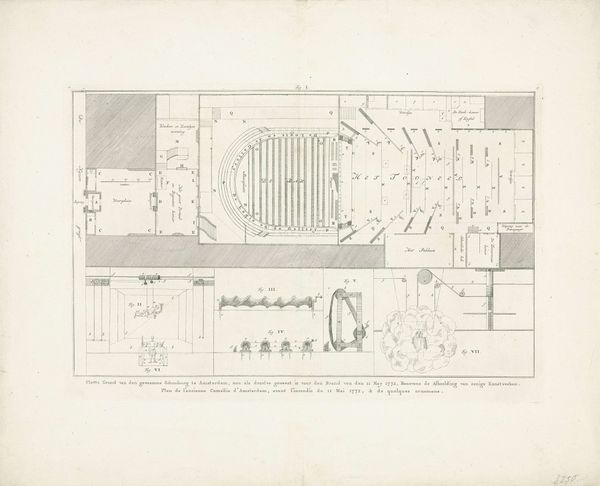

Dimensions: height 486 mm, width 648 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

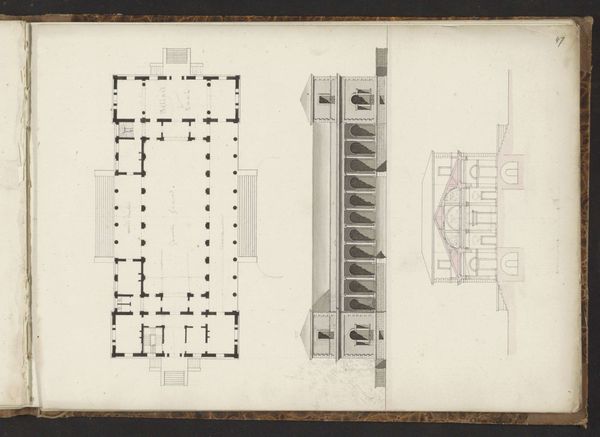

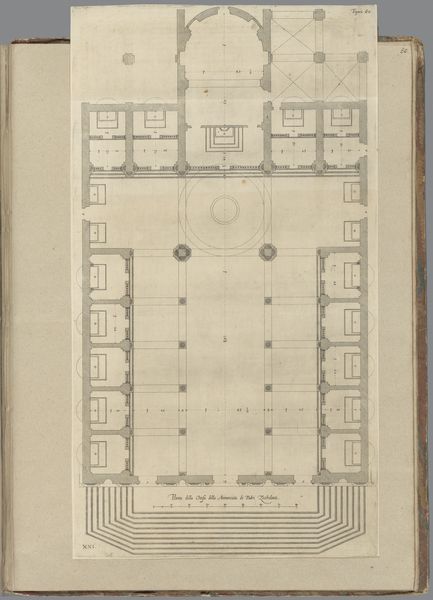

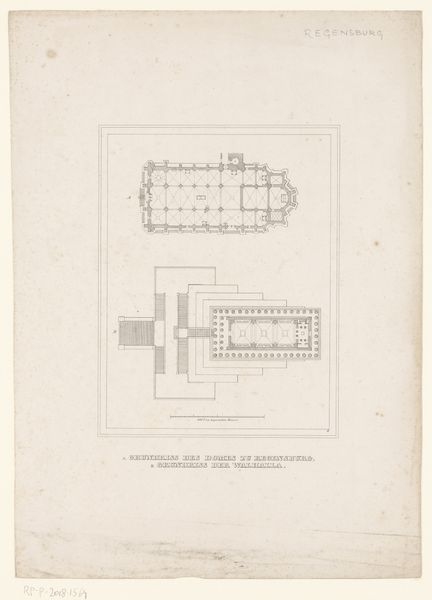

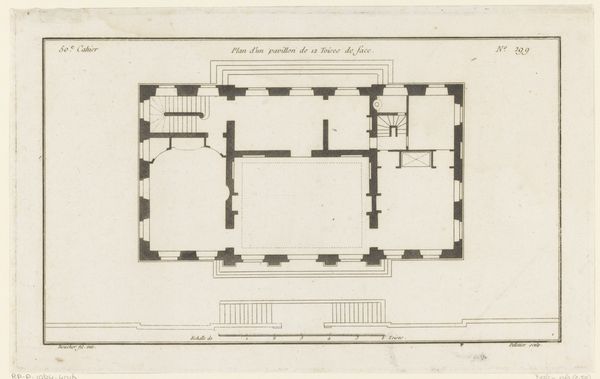

Curator: This intricate print, “Plattegronden van het Britse Hogerhuis en het Lagerhuis,” believed to be from around 1749 and attributed to John Pine, presents floor plans of the British Houses of Parliament. It’s an engraving on paper. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its precision and rigidity. The line work is so exact, creating these very formal and seemingly inflexible spaces. It gives the impression of order, perhaps to a fault. Curator: Indeed, this precision speaks to the Enlightenment ideals of reason and order. The engraving highlights not just the architecture, but also the social hierarchies embedded within these spaces, reflecting the very strict social structures in place at the time. One can argue that the rigidness is there to suggest how immutable the class structures of the time were supposed to be, a reflection of the British socio-political climate. Editor: Absolutely, the stark contrast between the empty spaces for representatives and the very physical throne implies that those rooms are shaped to enable only certain performances of power. You can sense how class relations dictate access to representation, even down to where one is permitted to stand. Are there any records that show that they were accurate? What does this tell us about how architectural and political knowledge were circulated as a printed matter at that time? Curator: Great questions. Printed plans like these were used to visualize and understand the power dynamics at play and also how those houses were planned according to them, thus becoming instruments of social and political reflection. Considering that very few had direct access to these spaces, the very material production and distribution of these kinds of prints highlights the circulation of this specific kind of cultural knowledge in 18th century society. Editor: I see. It all leads back to the structures, doesn't it? From the physical materials of the print itself to the institutional structures it depicts. We could understand it almost like an early form of what we might now call visual policy activism. Curator: That’s insightful. It becomes a material manifestation of those relationships of power, making the political realities and structures physically present for scrutiny, analysis, and even, hopefully, change. Editor: In this, these kinds of prints become a window not only into architecture, but the broader production of 18th-century knowledge about political access. Curator: Exactly, they are potent intersections of artistic representation, political ideology, and societal critique that open discussions on the production of material.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.