painting, oil-paint

#

allegory

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

roman-mythology

#

mythology

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

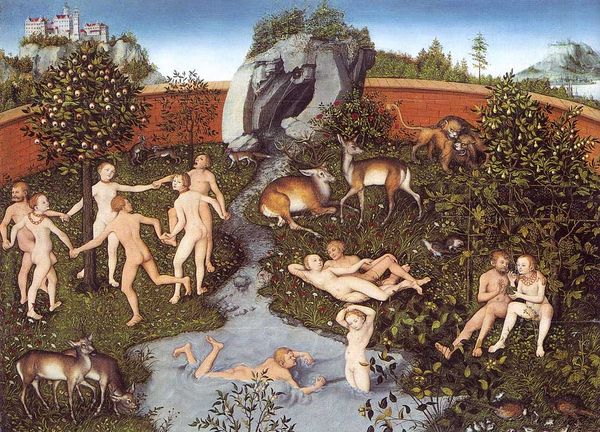

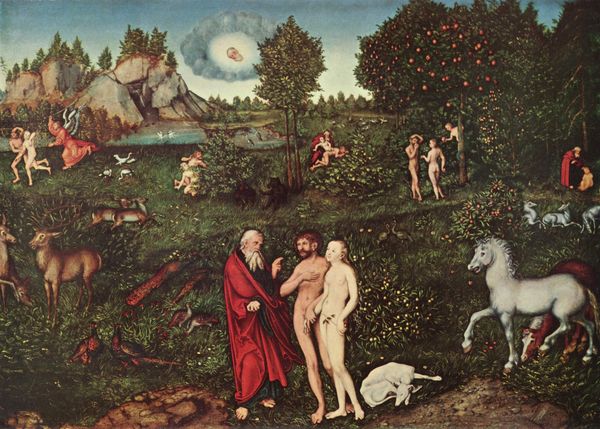

Dimensions: 73.5 x 105.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

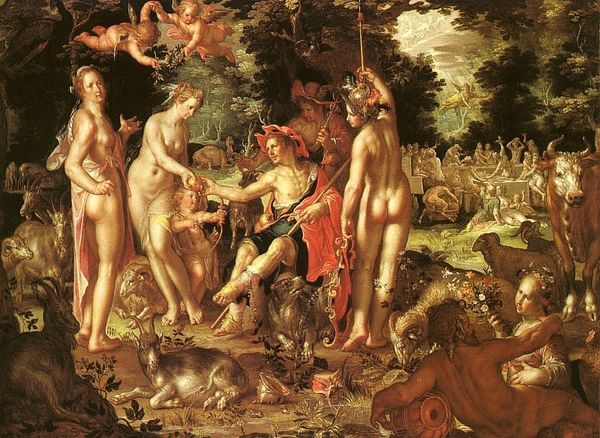

Curator: Immediately, what strikes me is this strange sense of serenity, but it’s tinged with something…unsettling. All these nude figures cavorting in a garden that feels both idyllic and strangely confined. Editor: Let’s unpack that. What we’re looking at here is “The Golden Age” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, painted in 1530. Cranach was a master of the Northern Renaissance, and this piece, currently residing in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, exemplifies his blend of classical mythology and Northern European landscape traditions. Curator: Yes, and that tension is palpable. There's a dreamlike quality – those pale figures almost glow against the deep greens and browns. It’s like a stage set, almost too perfect, too balanced. Makes me feel as if something’s about to go awry. Editor: It’s important to remember the socio-political context. Cranach was painting during the Reformation. This “Golden Age” is a clear nod to classical ideas of peace and prosperity, pre-civilization, pre-law. But these scenes also served a very didactic purpose for wealthy patrons. The idealized bodies—and idealized state—demonstrate complex politics about religion and virtue that prevailed throughout the era. Curator: That explains, in part, that odd, almost childlike innocence. Their bodies are strangely sexless, more like mannequins posed in a living tableau. But where does the “golden” part come in? To me it appears slightly melancholic rather than golden. Editor: Ah, that's the real complexity of the image, and the title. The Golden Age, as described by classical writers like Hesiod, was a time before hardship, before work, before societal rules. The figures’ nakedness reflects their perceived innocence, unburdened by shame. And it suggests that society may lead only to corrupt outcomes and behaviours. Curator: It all feels terribly loaded. A painted ideal, drenched in myth, to promote very earthly power relations. I mean, is there any real freedom being offered in a depiction such as this? Is that the "dream" it alludes to, only there for wealthy patrons of the time? It is certainly a provocative scene for thought. Editor: Exactly. These paintings present utopias—social orders, often gendered—but always as an allegory that justifies real-world inequities and power structures. As an activist I ask myself and others: What narratives continue from Cranach's time through to now, as it relates to ideas about our own virtues, shame, and who we think we are today as "innocent," when looking at artworks such as this. Curator: You’ve definitely shifted my perspective. It started as a scene of dreamlike figures in an eerie and artificial setting and now I see that is what it meant to portray! The painting invites a kind of critical look at our ideals. I almost wish it wasn't real! Editor: Ultimately, by acknowledging these tensions and contradictions, we can better understand not only Cranach's painting but also our own complex relationships with the past and what this can all possibly mean to the future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.