Copyright: Public domain

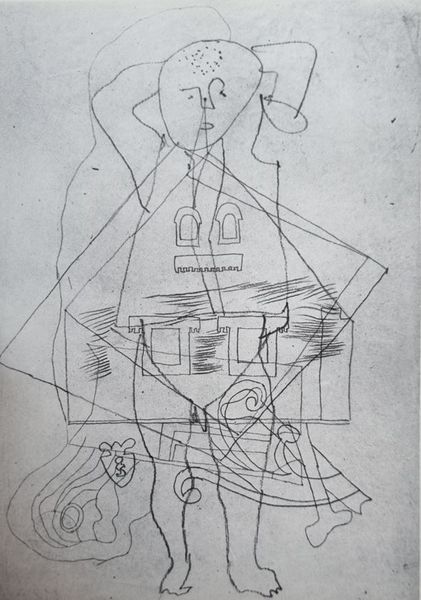

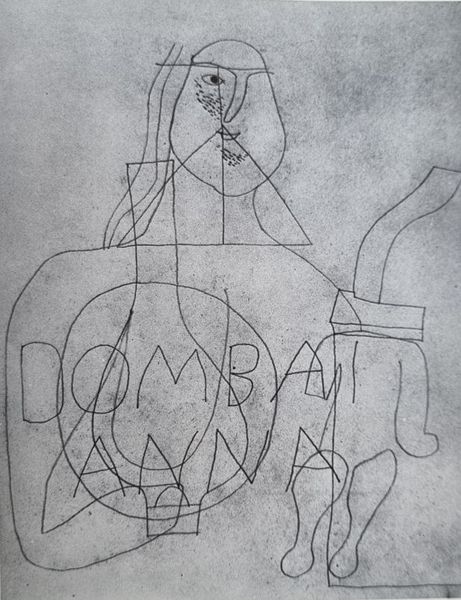

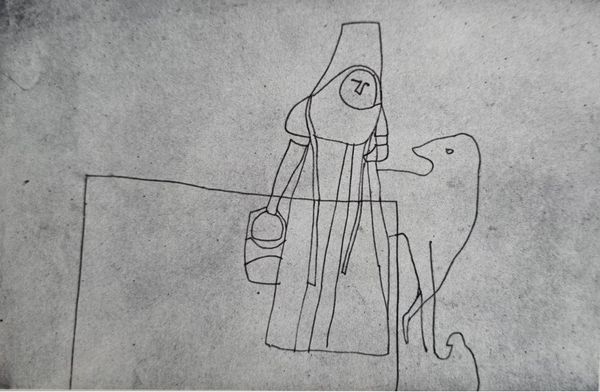

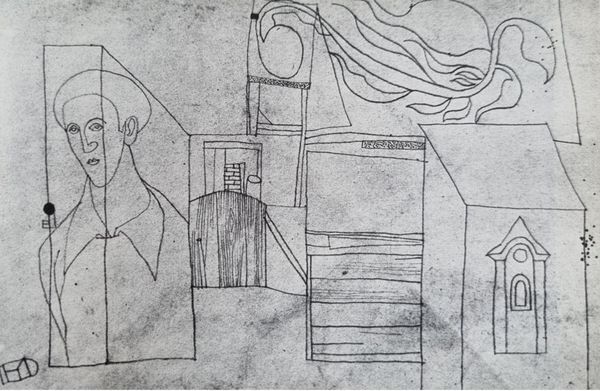

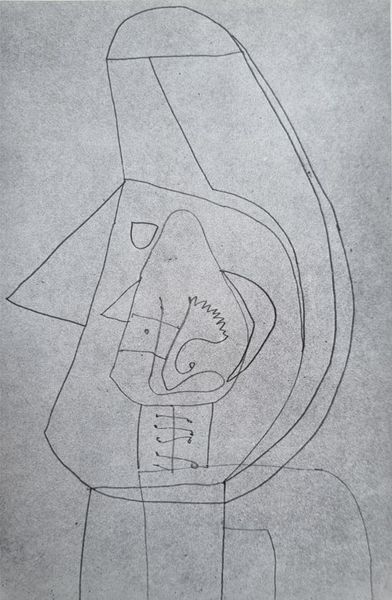

Editor: Here we have Lajos Vajda’s “Madonna above the Gate,” created in ink on paper in 1937. It feels like a ghostly blueprint, layered with religious symbolism. What do you see in this piece, considering its historical context? Curator: I see a fascinating interplay between religious iconography and modernist aesthetics, shaped by the socio-political turbulence of the 1930s. Vajda, positioned in interwar Hungary, presents a fractured Madonna, literally drawn over an architectural space. Considering that artists were often pressured by institutions, do you think he might be trying to say something about the Church’s position in society, or perhaps its relationship to architecture, to the very idea of building? Editor: That's a thought-provoking point. It's as if the spiritual is superimposed, maybe even struggling, against the physical structures. Could this suggest a critique of institutional religion versus personal faith, in a period ripe with societal anxieties? Curator: Precisely. The layering and the fragility of the ink drawing suggest a sense of precariousness. Look at the lettering as well – almost obscured, as if to suggest historical text being forcibly rewritten. What implications could such cultural modifications provoke in terms of public response? Editor: I never noticed the way those cultural layers obscure the spiritual figures, now I see how charged that must have felt to its original audience. I guess even a simple drawing like this holds within it entire social struggles. Curator: Yes, indeed. Even through its modest materials and intimate scale, this artwork echoes the larger societal shifts and contestations of its time. Editor: I've learned a lot about seeing artworks as evidence of their specific histories. Thank you. Curator: My pleasure. It’s important to remember art doesn't exist in a vacuum; it is always in dialogue with its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.