I Saw it, plate 44 from The Disasters of War Possibly 1810 - 1863

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, intaglio, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

intaglio

#

war

#

figuration

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 124 × 195 mm (image); 157 × 233 mm (plate); 240 × 340 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

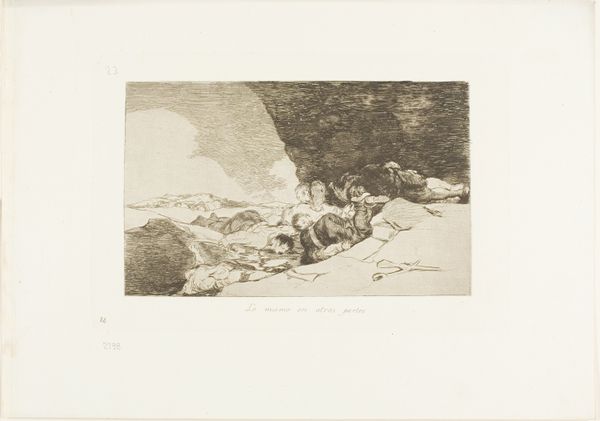

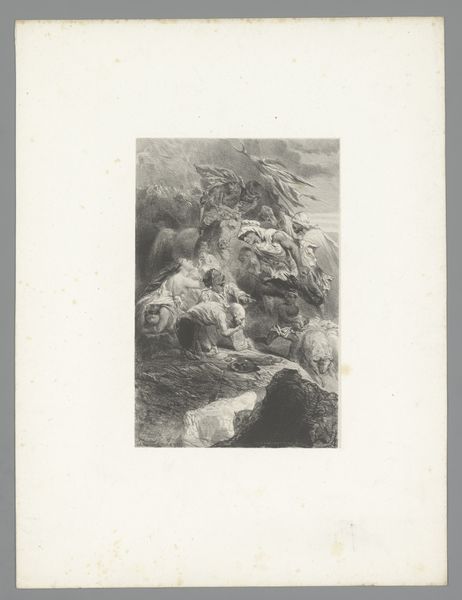

Curator: Francisco de Goya’s print, "I Saw it," plate 44 from *The Disasters of War*, made with etching and drypoint, likely between 1810 and 1863. I understand this piece resides at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: An immediate sense of stark brutality leaps from the page, doesn’t it? The way Goya manipulates shadow amplifies the distress and disquiet. Curator: Indeed. Notice the composition: the figures are thrust forward, creating a claustrophobic feel. Goya's deliberate use of line—thin, scratchy marks that coalesce to form figures caught in mid-flight— contributes significantly. There's a strategic distribution of light and dark. Editor: Light is granted to the victims here, no? The figures in shadow bearing down on them clearly wear the dark apparel of soldiers. The terrified woman clutches a child; the entire narrative speaks to universal horrors of war inflicted on civilians, a common image even today. We immediately know who represents ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Curator: Precisely. This is not just a depiction of violence but an appeal to our sense of morality. Semiotically speaking, consider what Goya is doing. These weren’t mass produced propaganda images to encourage more war, they represent individual acts of cruelty. Editor: The iconography feels deliberate. Goya witnessed the Peninsular War firsthand, and there's speculation if "I Saw it" indicates personal witness, underscoring its raw emotional power. What does it mean to show what you have seen? Curator: That adds another layer, certainly. Looking purely at its formal qualities, you observe a tension established through contrasting textures. Notice how he achieves depth despite limited tonal range? The blankness behind these individuals suggests emptiness, the end of the world itself, no place to run, nowhere to go. Editor: He gives no safe ground for the eye; everywhere, we see distress. Thinking historically, it transcends the specific conflict and morphs into a timeless statement against human cruelty. It serves as a memorial—not to heroism but to human suffering. Curator: And formally speaking, that emphasis on line rather than form directs the viewers gaze across every figure’s agonized expression in sequence. Editor: Absolutely, and on a personal level, knowing this image carries so many readings encourages continued introspection long after we’ve moved away from it. It asks a difficult, yet necessary question: how should the modern artist respond to violence and atrocities?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.