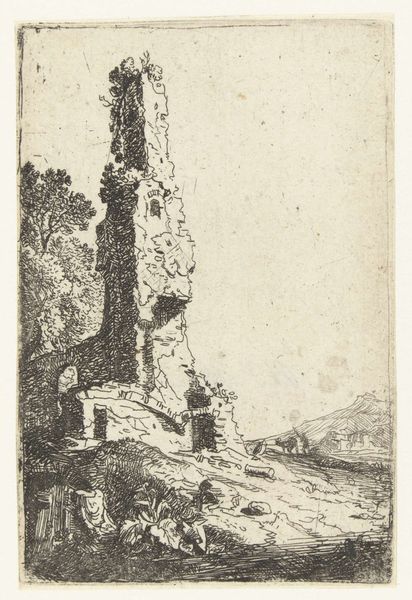

Plate 2: Calidarium at the Baths of Diocletian, with a man striding toward the right foreground, from the series 'The Ruins of Rome' 1640

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

romanesque

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: sheet: 3 7/16 x 4 3/4 in. (8.8 x 12.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s "Plate 2: Calidarium at the Baths of Diocletian, with a man striding toward the right foreground, from the series 'The Ruins of Rome,'" created in 1640. It's an etching. What strikes you most when you look at it? Editor: It's overwhelmingly melancholic. That figure walking away from us, almost disappearing into the overgrown ruins… It speaks to loss, to empires crumbling. There’s a strong contrast between the stark details in the foreground and the blurred landscape further away. Curator: Exactly. The Romanesque style, particularly this fascination with ruins, emerged alongside specific social conditions, class relations, and evolving imperial ambitions. We're seeing not just the documentation of a place, but a commentary on power and transience. Editor: Yes! The series’ title says it all: ruins. I keep thinking about who gets to write history. Consider how often perspectives like those of enslaved peoples who maintained those baths are sidelined when we glorify Roman architectural prowess and social organization. Curator: Breenbergh's work exists within a complex network of social and political forces. The Catholic Church, powerful families and individuals like the Borghese, Barberini, and Pamphili families were its primary sponsors, actively promoting interpretations that reinforced their own ideologies and control. The public function of the image was vital for political display, especially during the Counter-Reformation. Editor: The contrast of darkness and light in the print heightens its inherent tension; I’m drawn to the small group of people emerging from the gateway. One can imagine these survivors forging new paths within decaying structures. Are they reclaiming these ruins in some way, creating new spaces out of the old? Curator: It raises important questions about the cyclical nature of power and resistance. Breenbergh prompts us to look beyond aesthetics and ponder these ruins' role in larger historical narratives. Editor: This makes me think of queer spaces carved from places of oppression and/or abandon: subverting old norms, rebuilding. It’s a reminder that even from what appears destroyed, something new can flourish. Thanks for adding further insight to this etching. Curator: My pleasure; I think these conversations push us beyond a simple appreciation of skill. It is powerful to reconsider how art serves dominant powers and allows space for challenging such dominance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.