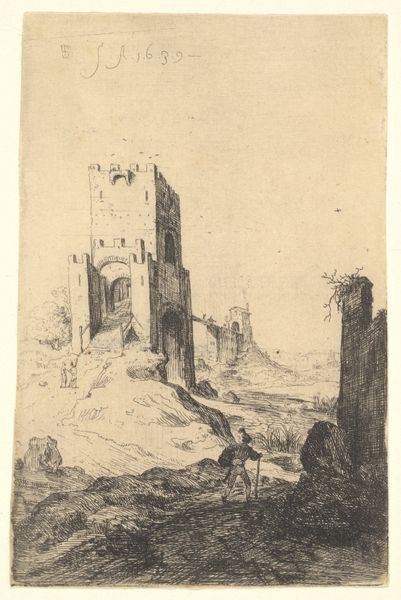

print, etching

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

realism

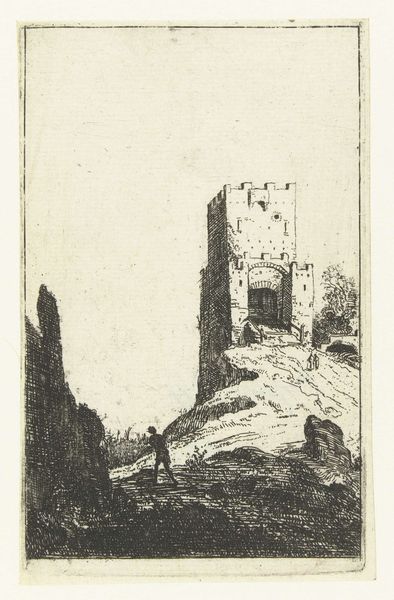

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It’s hard to miss the solemn presence in this etching by Bartholomeus Breenbergh. This is "Ruins of the City Walls of Rome," created around 1639 or 1640. The artist has etched an old ruin, likely a tower, amidst the Roman Campagna. Editor: Immediately I notice how delicately worked the scene is, almost fragile, though its subject matter, a ruined structure, is decidedly about time and its effects. I want to run my fingers over the textured paper; feel the burr of the etched lines. Curator: The ruin dominating the composition becomes almost a symbolic ruin, a witness to the vicissitudes of power, time, and memory. It’s been said that ruins can signify cycles, rebirths even, resonating across cultures. What kind of collective emotions and images does the tower evoke? Editor: It certainly reflects a melancholic gaze, typical for the 17th-century artist depicting Rome as a layered material history of the making, unmaking, and remaking of empire. An etching allows for infinite reproductions to fuel collective consciousness, right? Also, there are some curious dark patches, where one imagines the acid bit deep into the metal. Curator: Absolutely. Breenbergh, working from his base in Amsterdam, wasn't simply documenting architecture. Instead, it almost feels as if he were engaging with the past itself. We can assume the location of the print to have aided in circulation of not only historical document but a symbolic weight that shifted the culture's relation to the Roman empire, and what it symbolized. Editor: One thinks of the labor invested; the artist coating the metal plate, meticulously incising lines, repeatedly submerging the plate in acid, each "bite" demanding precision, a close monitoring. This contrasts so profoundly with the dilapidation suggested within the pictorial space. There's something deeply poignant there. Curator: Looking at this from the 21st century, in what ways might this etching urge viewers toward certain perspectives on our present structures of power, knowledge, or permanence? Editor: Seeing the material processes involved – the degradation of the plate with each etching pass to spread imagery far and wide—has prompted a reconsideration on our understanding of how such images shaped social perception of place and history. The labor of material production tells another important story of its impact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.