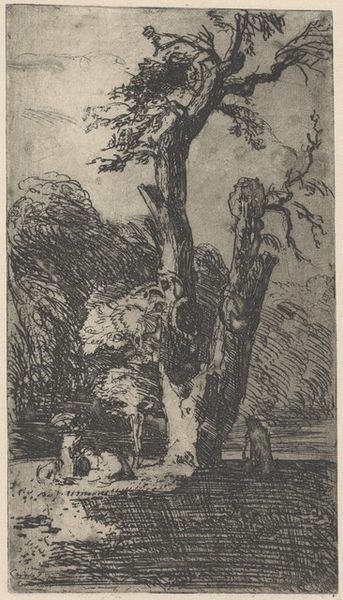

drawing, etching, paper, ink, frottage

#

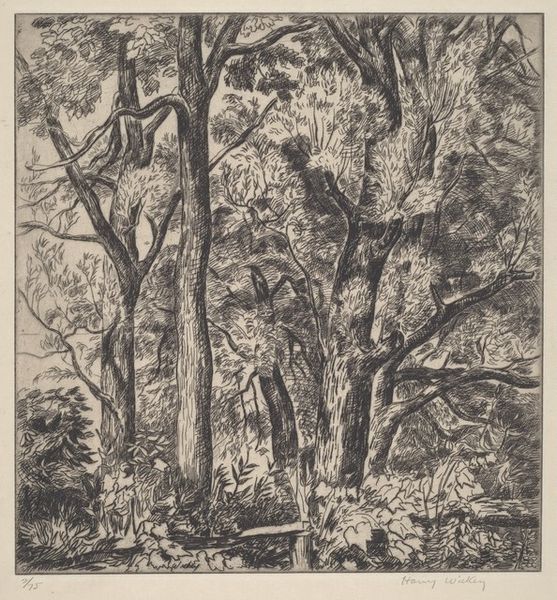

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

frottage

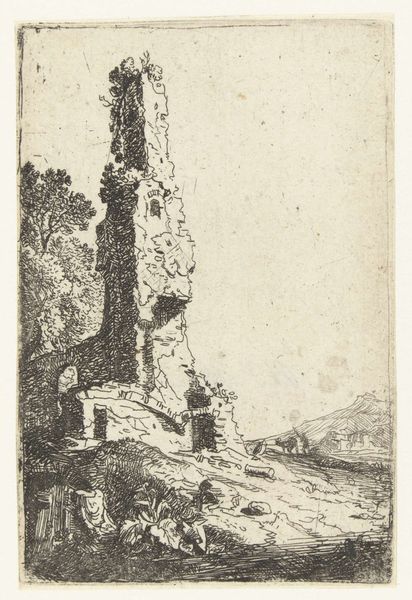

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right, let's talk about this etching by Bartholomeus Breenbergh, titled "Ruins of San Lorenzo Vecchio near Bolsena," created around 1639-1640. It's a rather evocative scene rendered with ink on paper. Editor: Ah, yes, it whispers of time, doesn't it? Makes me feel like I'm stumbling upon some forgotten dream. I love the immediacy of the line work, all those hurried scratches and flicks...it’s so textural. Curator: Indeed. Breenbergh, a key figure in the Dutch Italianate landscape painting tradition, used etching here to capture not just a physical space but also a certain mood linked to the Roman Campagna. The print medium meant the image could circulate widely, influencing tastes for certain kinds of scenery. Editor: You know, it feels almost rebellious, letting the wild foliage reclaim the stone. Those crumbling walls, overtaken by nature, they hint at the impermanence of human endeavors. What was the role of the antique for viewers back then, I wonder? Was it simply an exercise of historical curiosity, or something more pointed? Curator: That’s a critical point. Certainly, part of its appeal was linked to the Grand Tour and the classical revival. But it's also important to consider how prints like these catered to, and even shaped, ideas about Dutch identity, their relationship to the past, and notions of civic virtue tied to their own built environment in the Netherlands. There was almost a comparative exercise involved, a statement about what endured. Editor: So almost an allegory about legacy, viewed from a comfortable, and culturally specific, distance? This Breenbergh almost lets us write our own ending on this bygone monument. I love it! Curator: Exactly. Through distribution and access, the image itself becomes a tool. What begins as artistic creation morphs into a mirror reflecting viewers' beliefs, power and ideals. The afterlife of an image indeed! Editor: It gives the etching more complexity knowing Breenbergh might be making us think about what his viewers thought about permanence, and what exactly they sought in their visions of an evocative vista. The dialogue created between the viewer, the vista and the history involved transforms the whole viewing experience. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.