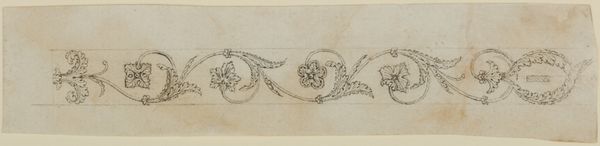

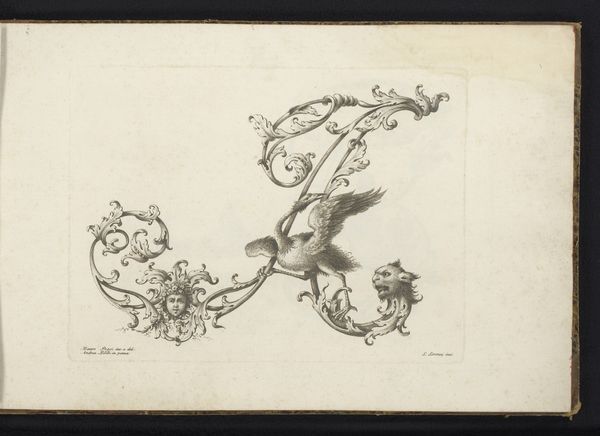

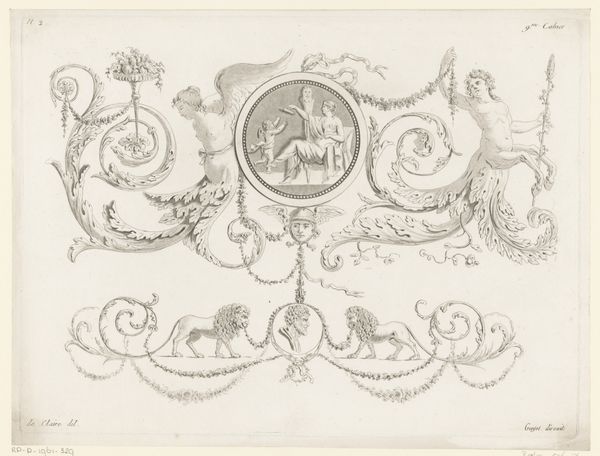

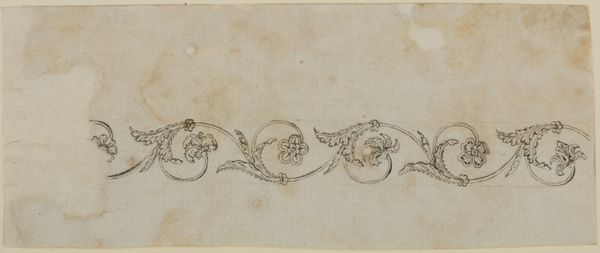

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

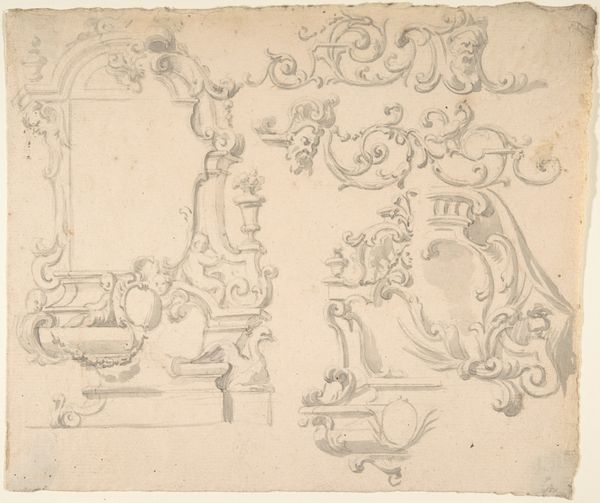

drawing

#

allegory

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

symbolism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 418 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intricately rendered work, crafted around 1866 by Michel Liénard, presents what is titled "Bladrank met gevleugeld monster met vogelkop"—or, translated, "Leaf scroll with winged monster with bird's head." Executed in ink, colored pencil, and engraving on paper, it promises a dive into fantastical realms. Editor: Immediately, I see the blend of the grotesque and the graceful. It feels like a page torn from a medieval bestiary, a space where sacred geometry meets dark humor. How would this have been perceived, socially and artistically, in its own time? Curator: The piece really exemplifies the rise of Symbolism during that era. Liénard skillfully interweaves these somewhat unsettling figures—winged monsters, demons, and that peculiar bird-headed creature—within swirling vegetal motifs, hinting at the veiled symbolism and the hidden worlds popular at the time. The use of these hybrid creatures touches upon a much older tradition, linking back to ancient mythologies and the medieval grotesque, embodying societal fears and desires through such strange yet oddly familiar symbols. Editor: Precisely! Those historical threads make the work so compelling. The arrangement, confined within the neat border, strikes me as an act of containment. Society's attempt, perhaps, to order these unruly aspects of human experience or folklore. I wonder what social forces drove that impulse towards control, or classification? Curator: You highlight a vital point about social ordering. And think about it - winged creatures were also associated with transcendence and the divine! The infant figure incorporated into the vine brings Christian allegories into play, creating complex emotional tension. Liénard does not just show the fearful. There's a deep cultural memory and, quite frankly, visual humor on display. Editor: Yes, visual humor absolutely. But was that the common reading in the 1860s? What galleries or public spaces displayed such art then? Because its placement really dictated its function and social reception, right? Curator: A challenging question, really! While Symbolist art wasn't confined solely to established galleries, it certainly sparked discourse and challenged conventions through exhibitions in smaller salons or through publications, gradually finding its niche in a society undergoing dramatic transformations and realignments in power and aesthetic values. Editor: This piece is like a curious key unlocking dialogues about visual language, belief, social tension, and artistic evolution. I could get lost for hours thinking about where it came from, and where it might lead. Curator: I couldn't agree more. Exploring that dialogue—that conversation with the past—is precisely where art like Liénard's finds renewed significance, reminding us of the cultural threads that persist across time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.