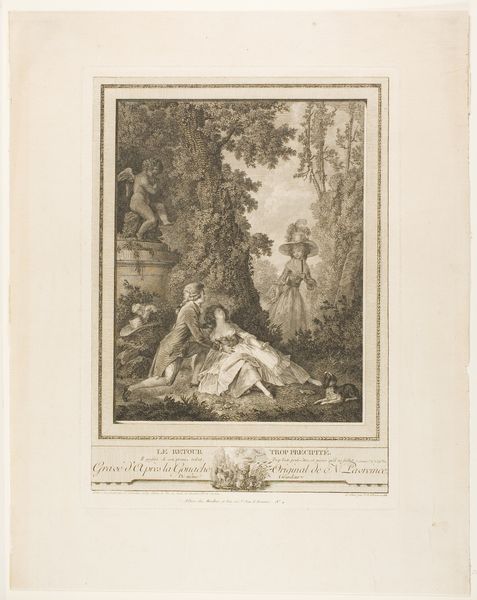

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

lithograph

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 182 × 146 mm (image); 355 × 260 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This lithograph is titled "Une Lecture", dating from 1822, created by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon. It's currently housed here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It strikes me immediately as melancholic, almost fragile. The monochromatic tones emphasize a stillness, a private moment caught in time. Curator: That fragility is interesting in relation to its wider reception, and Romanticism. It really plays on ideas about women being quiet muses to the artist in a domestic and therefore public context. The imagery would reflect sentimental tropes back to Prud'hon's wealthy patron base. Editor: Precisely, the dove—a classical symbol, of course, of love and peace but I feel, too, it signifies the soul. See how the woman leans into the bird, inviting a kind of spiritual communion through nature. Notice also the subtle emphasis, typical in Romantic work of this era, of blurring the lines of demarcation: where does woman end, and animal begin? The dove is her familiar. Curator: What's always fascinated me about works such as these, within the larger framework of museum collecting, is to wonder how something so intimate transitions from private to public consumption. Prud'hon created this print so it could be dispersed. Where were copies like these hung, and why? This image also has an overtly French aesthetic, how has it impacted US collecting tastes since then? Editor: And the flowers! These would have been potent signifiers for Prud'hon's viewers. I think of innocence, of budding youth…of fragility of life, again! The vase almost looks to have weeping angels, and has clearly seen better days. But they could have many alternative, now dormant meanings depending on species: a botanical rhetoric lost to us. The print asks us to consider this gentle woman in her interior world, the world in which she holds meaning in tension to nature and symbolism. Curator: It shows that this simple domestic image is carefully constructed in an arena where gender roles and artistic ambition are constantly shifting, a visual power-play between patron and producer that we can't ever fully know. I wonder how different an interpretation a contemporary woman would feel now versus someone who looked at the artwork during that period? Editor: It truly underscores the fascinating multiplicity of visual interpretation that these sorts of discussions evoke! We see it as intimate because it has made it across history. But it must have meant something very different indeed in situ.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.