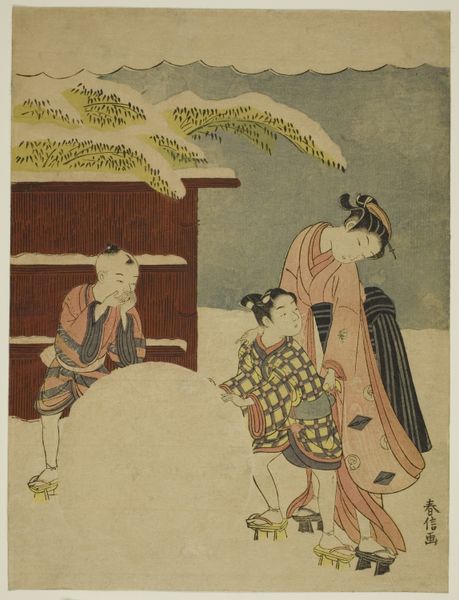

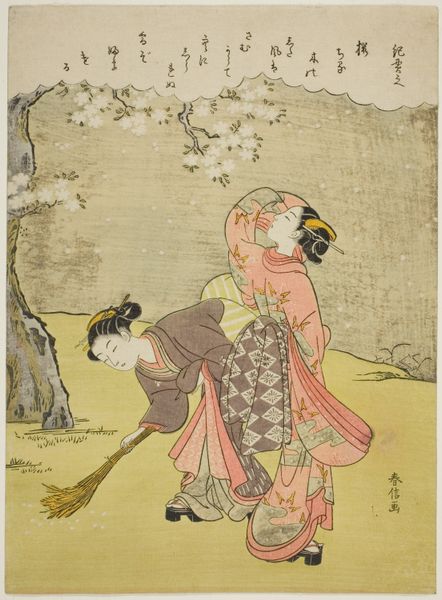

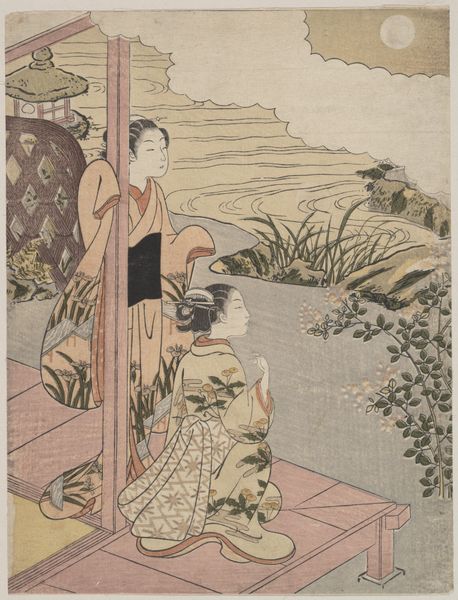

Parody of the Legend of Kyoyu and Sofu 1764 - 1772

0:00

0:00

painting, print, watercolor

#

water colours

#

ink painting

#

painting

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

watercolor

Dimensions: H. 10 3/4 in. (27.3 cm); W. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: At first glance, there’s something very calming about the tonality of this print. A figure sitting serenely before a waterfall. Editor: That's a wonderful initial response. What we're looking at is Suzuki Harunobu's "Parody of the Legend of Kyoyu and Sofu," created sometime between 1764 and 1772. It is currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curator: Parody, you say? Well that shifts things. Can you tell me about that? Is it an actual painting, or a print reproduction of something? The Met identifies this work as a color woodblock print, specifically an *azuma nishiki-e*. Editor: The legend is a Chinese story about an aristocratic hermit who refused to serve the emperor and washed his ears in a stream to cleanse them from the emperor's offer, while another hermit refused him access to the clean water upstream. Harunobu’s parody replaces those hermits with a young woman. As a *nishiki-e* or "brocade print," this uses multiple blocks to achieve its layered colors. Look at how different colours have been expertly printed in perfect registration to build up layers of the image. Curator: Absolutely, the surface treatment, that precise carving of the blocks and layering of ink and watercolor creates such a complex, yet controlled image. I notice her elaborate garments--and I suspect these patterns printed on her clothing hold cultural significance, too. Editor: Good point. The luxurious patterns on her kimono and the overall elegance suggests a commentary on contemporary life. The woman's presence near the waterfall—an element of classical narratives—might critique the elite class, positioning their leisurely existence in contrast to more austere, traditional values. We should think about how images circulate within the urban centers, not only how it represents those groups but how they understand its message. Curator: So, the context, its placement within both printmaking and the social hierarchy is crucial. Fascinating how the artist used accessible, mass-produced imagery like Ukiyo-e, in turn commenting on political elitism. And how the material of the print—the wood, the inks, the paper—itself democratizes the artwork. Editor: Exactly, thinking about art in terms of access, politics, labor is what really brings works like these into relevance, as the work also challenges long held beliefs. Curator: Indeed. I see now that what I thought was a serene landscape has complex commentary below the surface. Editor: Absolutely. It's those subtle contradictions which allows us to read historical narratives in relationship to material practices.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.