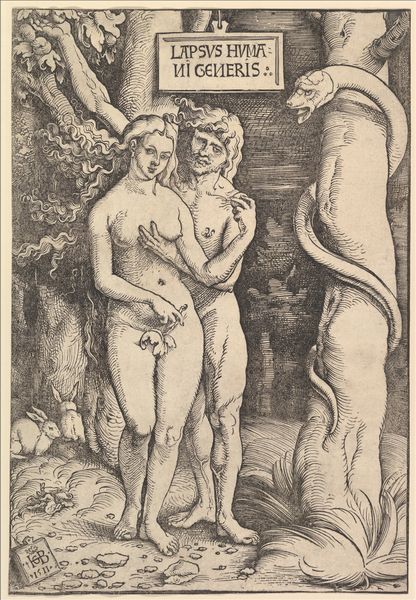

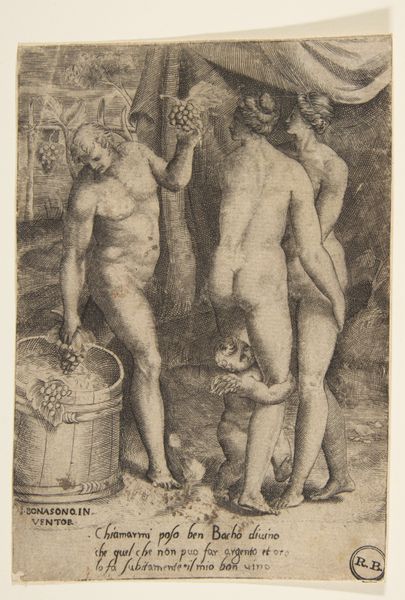

Jongeman beschermd door vrouw met globe en offerschaal als personificatie van Fortuin (Fortuna) 1506 - 1507

0:00

0:00

marcantonioraimondi

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

form

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 89 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Marcantonio Raimondi's engraving from 1506-1507, titled "Young Man Protected by a Woman with Globe and Offering Bowl as Personification of Fortune (Fortuna)." I'm struck by the somewhat precarious balance of the figures. What's your interpretation of this piece, especially considering the social context of its creation? Curator: This engraving is fascinating because it reveals so much about the societal roles artists and their patrons played during the Italian Renaissance. Raimondi was not just creating an aesthetically pleasing image; he was participating in a dialogue about fortune, protection, and perhaps, anxieties of the era. Look at how the male figure is dependent on Fortuna; how might this image speak to the patronage system of the time, where artists themselves were dependent on the "fortune" of finding wealthy sponsors? Editor: That’s an interesting point about patronage. So, is the young man’s reliance on Fortuna a commentary on the artist’s own dependence? It seems to normalize male dependence on powerful, even divine, women. Curator: Precisely. And beyond the individual artist’s circumstances, consider the broader political landscape. Images of Fortuna were often associated with the volatile nature of power and political alliances. This print, circulated amongst the elite, could have served as a reminder of the ever-shifting sands of fortune and the need for protection – both literal and symbolic. Notice the inclusion of the landscape; does it reinforce this idea? Editor: I see what you mean. The dense, almost overwhelming landscape seems to mirror the unpredictability of life itself. What do you make of the rather bold nudity? Curator: Ah, the nudity! It was not simply for aesthetic reasons, but a direct engagement with classical antiquity. The use of nude figures harkened back to a supposed golden age, but at the same time such nudity made this image available, as accessible erotica for an elite educated and well-off audience. Editor: This print, now viewed in the rather calm setting of the Rijksmuseum, clearly spoke volumes within its original cultural and political moment. I see how crucial it is to look at the function of art in Renaissance society and how its images can be read through its historical reception. Curator: Absolutely. It’s about uncovering how the artwork participated in the conversations, anxieties, and power structures of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.