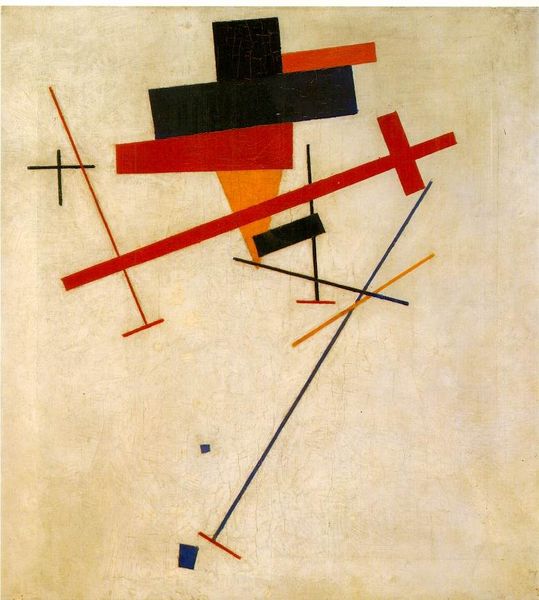

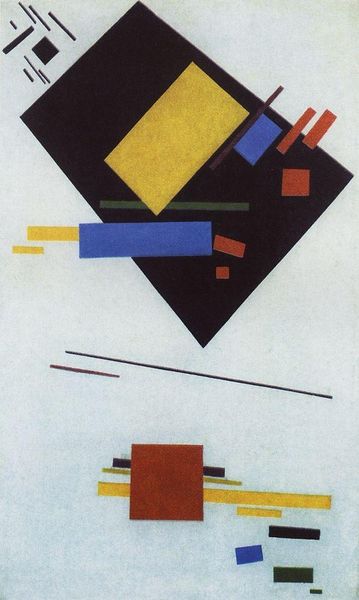

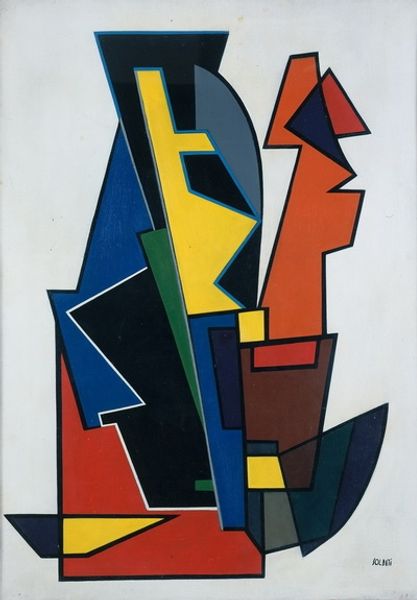

Dimensions: 44.5 x 35 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: We’re looking at Kazimir Malevich's "Suprematism," painted in 1915. It’s striking how such simple shapes—squares, rectangles, lines—create such a dynamic, almost chaotic energy on the canvas. What's your take on this piece? Curator: It's important to remember the Russia of 1915, teetering on the edge of revolution. Malevich wasn’t just arranging shapes; he was attempting to create a new visual language, one that broke free from the baggage of the past. It was a radical, even utopian, project. These basic geometric forms—the foundation of all things, according to him—are liberated from representation. They weren't trying to depict objects or people anymore. Editor: So, it’s like he's creating a visual tabula rasa? But did the public receive this “new language” well? Curator: That’s a great way to put it. But understandably, public and critical reaction was mixed. Many people didn't understand it. To them it looked like meaningless, even childish daubs of paint. But others saw it as a radical, groundbreaking statement, a rejection of the old order, and a bold step into an unknown future. How do you think institutions, then and now, play a role in validating art like this? Editor: That’s something to think about – without the backing of museums and galleries, would Suprematism have ever become so influential? Thanks, I’m looking at this very differently now. Curator: Absolutely! And think about the political implications, the desire for radical change echoed both in art and the streets of Petrograd. These shapes were potent symbols within a very specific cultural and historical context. A painting like this demonstrates that abstraction isn't separate from society; it's deeply intertwined.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.