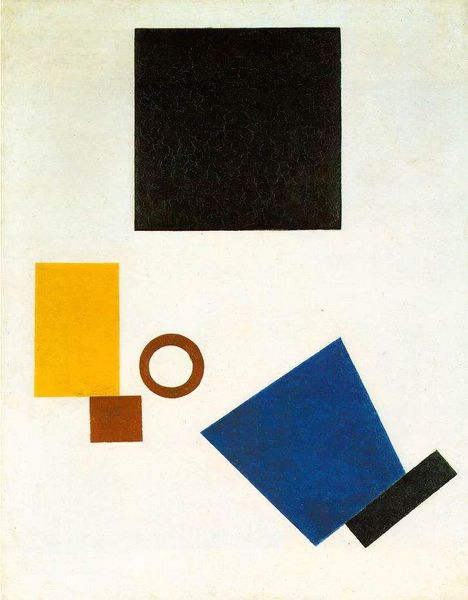

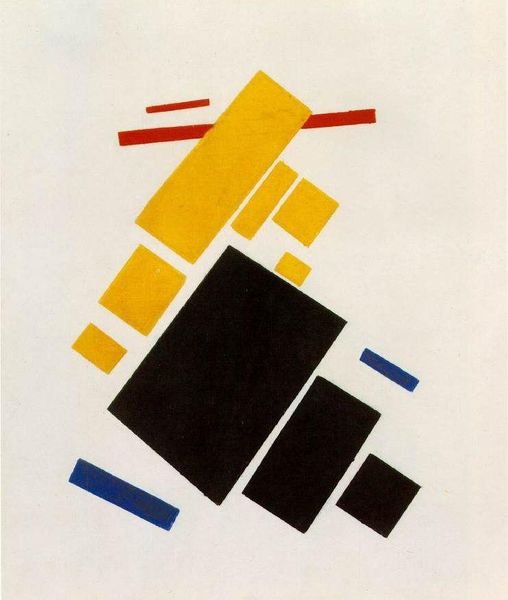

Copyright: Public domain

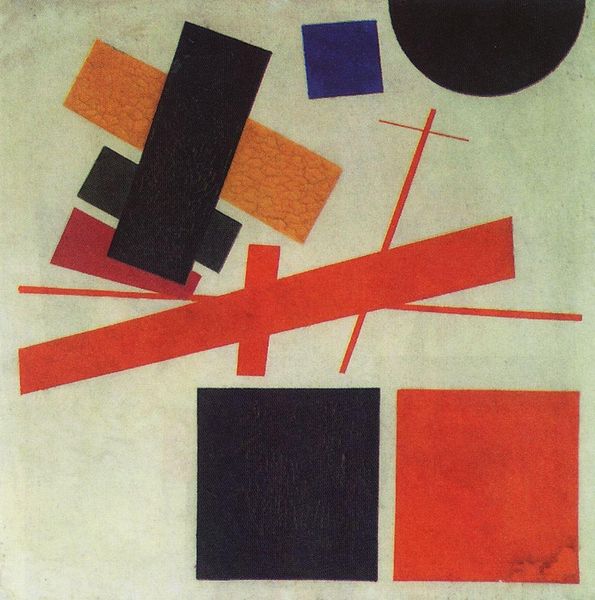

Curator: Gazing upon Kazimir Malevich’s “Suprematism,” painted in 1915, now residing at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, I’m immediately struck by its radical simplicity. Just geometric shapes adrift on a white field. Editor: Yes, there is something serene yet unsettling about its lack of any clear focal point. It feels weightless, almost as if the shapes are floating in a vacuum. What was Malevich trying to achieve with this language of pure abstraction? Curator: Malevich sought to transcend representation. He developed Suprematism as a system to express, through pure geometric forms, what he felt was the supreme reality – a reality beyond objective vision. This painting, made with tempera, is one of his key expressions of those sentiments. Editor: So, it's a complete break from depicting the external world and towards a purely spiritual and intellectual exercise. Yet, I wonder about the societal context. The Russian avant-garde was deeply involved in revolutionary fervor. Was this abstraction itself a kind of political act? Curator: Precisely! The rejection of figurative art can be seen as mirroring the revolutionary spirit, breaking from the old order. Art should reject everything, be pure, and free in the new modern age. And consider the politics of display itself, and how Malevich pushed for access to new art spaces as spaces for collective and democratic access, away from elite patronage. Editor: Interesting. The monochrome palette adds to that sense of detachment, doesn't it? Restricting colour allows to be interpreted freely within social or philosophical frameworks, depending on how it’s viewed, as the world is itself diverse and colorful. Curator: Absolutely. "Suprematism" is far more than simple geometric forms; it is a revolutionary statement that radically shifted the direction of art, its goals, its aims, and who it should benefit, and, through time, transformed the direction and impact of art across society. Editor: Seeing it within that framework offers a powerful new reading. This painting, with its stark aesthetic, speaks volumes about its historical moment and asks questions about the function of artistic creation. Curator: Indeed. Understanding “Suprematism” through the lens of revolutionary theory opens the discourse about who gets to create art and what purpose it serves. Editor: Well, this brief contemplation definitely ignited some ideas, and inspires one to question those boundaries and functions more. Curator: It certainly does for me as well, it provides some insights that resonate beyond the aesthetic domain.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.