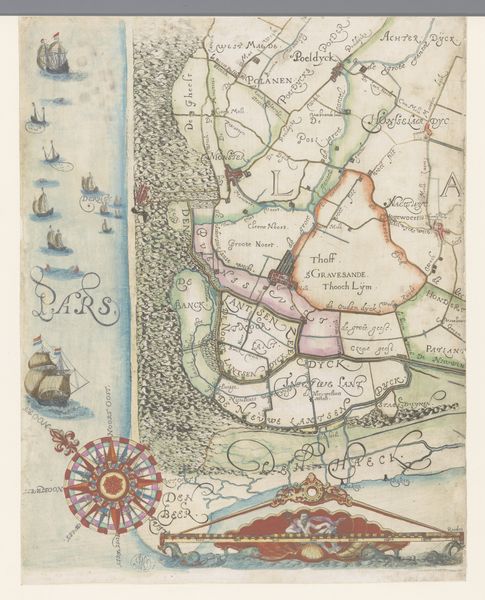

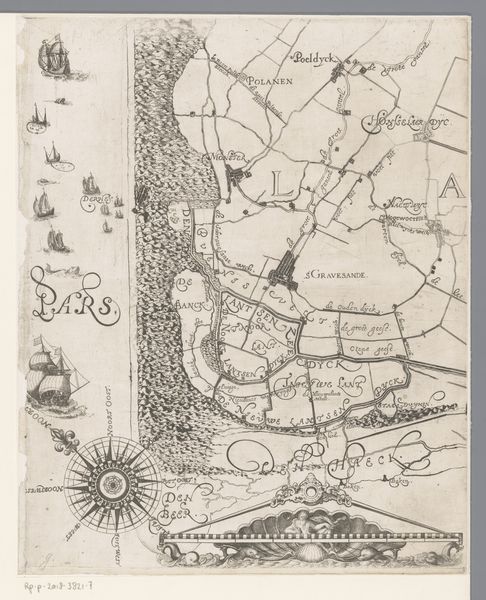

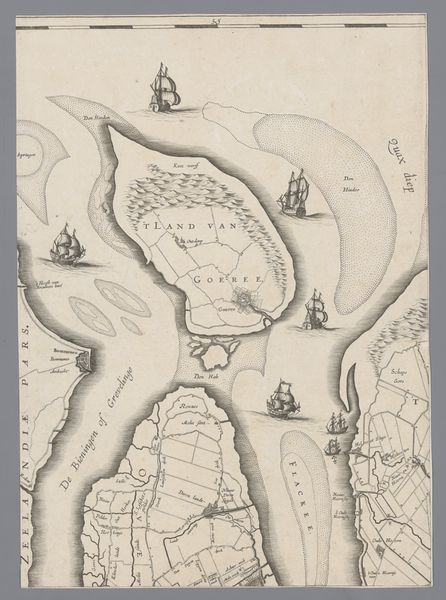

Deel van een kaart van het Hoogheemraadschap van Rijnland, met Huis te Boekhorst 1615

0:00

0:00

florisbalthasarszvanberckenrode

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

early-renaissance

Dimensions: height 363 mm, width 285 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

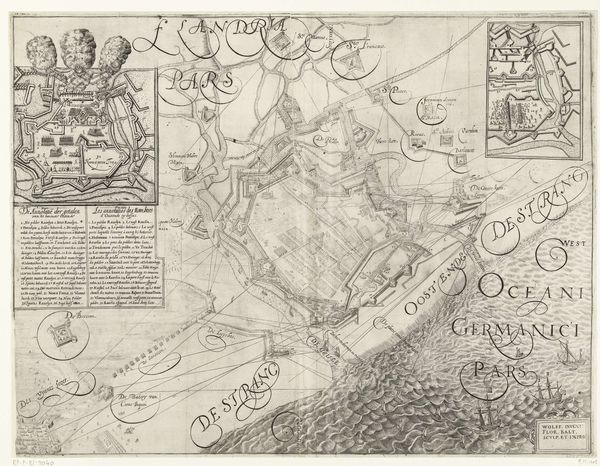

Curator: This intriguing piece is entitled "Deel van een kaart van het Hoogheemraadschap van Rijnland, met Huis te Boekhorst," or "Part of a map of the High Water Authority of Rhineland, with Huis te Boekhorst." Created around 1615 by Floris Balthasarsz van Berckenrode, it is rendered in drawing, watercolor and coloured pencil on paper. Editor: There’s something dreamlike about the cartography here. The two fantastic sea monsters lend the rendering a certain mythical weight, especially juxtaposed against the compass rose and rendered bodies of water. It's a navigational tool that transcends pure utility, reaching something evocative. Curator: Yes, there’s an overt blending of the functional and the symbolic. Berckenrode meticulously captures the region’s topography but integrates this with the emblems of Dutch maritime power. Consider how the deployment of watercolor emphasizes both the watery terrain itself but also implies the influence this landscape has on societal formation and expansion. Editor: Absolutely, the work invites us to consider how early modern Dutch society leveraged a landscape. Its watery qualities appear both bountiful and menacing, creating the demand and rationale for something like the High Water Authority of Rhineland. It raises questions about reclamation projects as inherently social, not strictly infrastructural undertakings. How were materials sourced? What labor forces built these structures? What communities benefited from the Huis te Boekhorst depicted? Curator: Precisely, this rendering provides fertile ground for semiotic analysis. Observe how the Huis te Boekhorst is positioned within the pictorial field; its placement acts as a locus for socio-political interpretation. The house becomes a visual signifier, directing our attention toward the interplay of power and property within the Rhineland region. The landscape itself becomes a codified space. Editor: It is almost diagrammatic, an idealized snapshot removed from the complicated manual processes of landscape alteration and urban development it implies. The almost jewel-like, highly crafted qualities here feel quite divergent from the messy reality of a Dutch landscape at the height of its mercantile activity. Curator: A telling friction, indeed. Perhaps through this, we can re-imagine how this era saw itself by carefully studying their materials, forms and intended meaning. Editor: Or perhaps reimagine how that self-representation, as mediated by the physical world and rendered labor, helped produce lasting societal structures we continue to engage with today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.