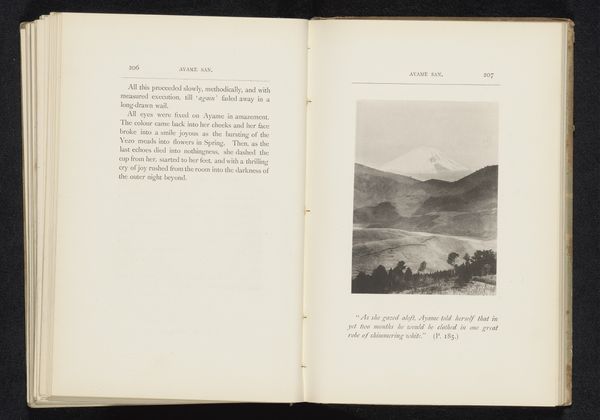

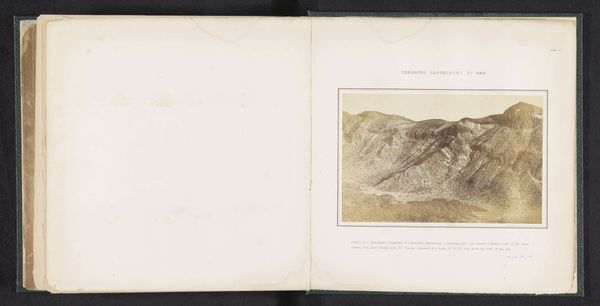

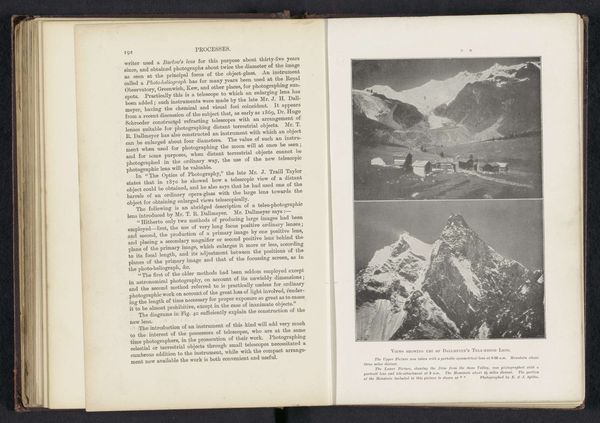

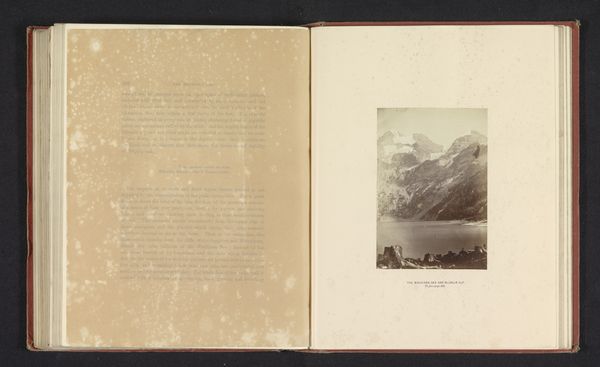

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

mountain

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, captured before 1895 by Dwight Lathrop Elmendorf, is titled "Castor and Pollux," and presents us with a serene yet imposing mountainous landscape. Editor: My initial reaction is awe mixed with a slight chill. The monochromatic palette heightens the starkness of the mountains. They appear almost otherworldly. Is it just me, or does the lack of human presence contribute to a feeling of isolation? Curator: That sense of isolation is interesting. Landscape photography in this era, late 19th century, often reflected the anxieties of industrialization. There's a prevailing narrative of nature as sublime, untouched, and a refuge from the rapidly changing world. The title referencing Greek mythology further elevates the scene beyond the earthly, inviting allegorical interpretations of the human condition in relationship to nature. Editor: Ah, the twin brothers! One mortal, one immortal, eternally linked... does the framing or composition suggest that duality, that tension between the finite and the infinite? Maybe that’s reaching. What exactly can you tell me about that “untouched” narrative you mention, and whose narrative exactly *is* that, I wonder. Curator: Well, photography, especially as it gained popularity, was closely tied to ideas of progress, but it also fostered a romantic vision of wilderness as the ultimate counterpoint to civilization. "Castor and Pollux" plays into this, presenting the mountains as formidable, majestic entities almost challenging human control or intervention. At the time these sorts of expeditions also functioned to underscore white and Western conceptions of "mastery," of seeing, documenting, and possessing a kind of cultural capital by displaying these lands. Editor: It’s funny that it can do both: participate in that narrative and reveal how damaging it is. I look at this now and wonder what the local inhabitants might have called these places, what stories or histories predated our seeing, knowing, documenting, and renaming them for our Western mythologies. The image still stirs a sense of longing for vast, untouched spaces but now also makes me very aware of what that desire papers over. Curator: Exactly. This photograph encapsulates the complex relationship between humanity and nature, progress and tradition, documentation and control. Editor: The tension of seeing beauty, appreciating technical skill, while recognizing that what we are really viewing is a symbol of complex power dynamics and, really, environmental vulnerability. I think, regardless of Elmendorf’s original intention, his photograph prompts urgent conversations for today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.