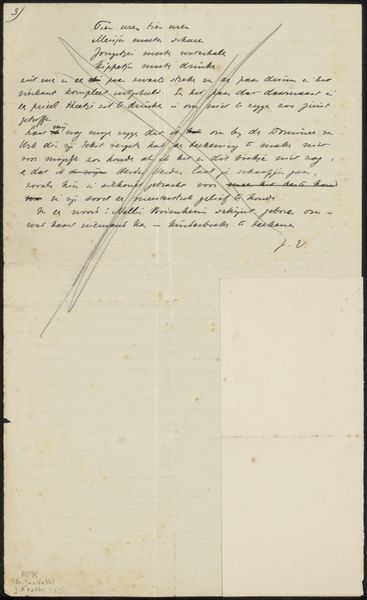

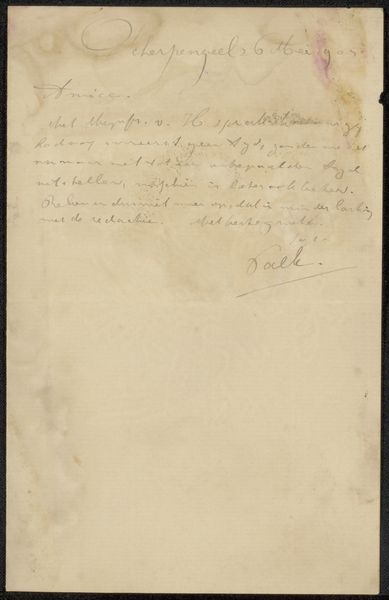

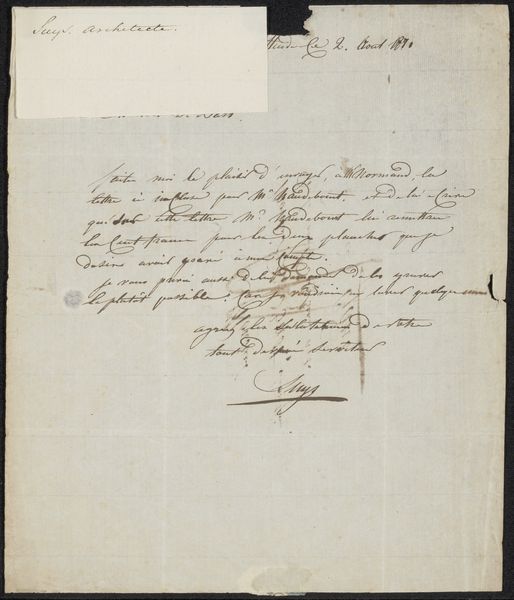

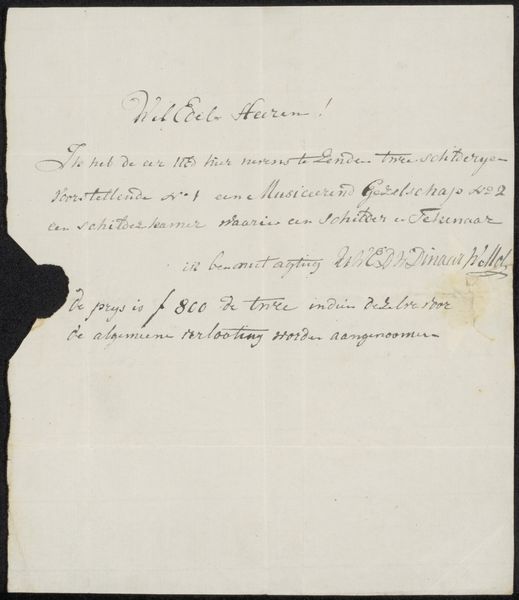

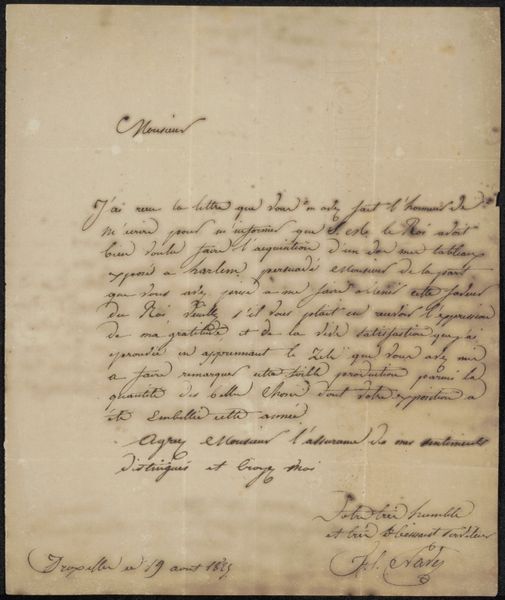

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

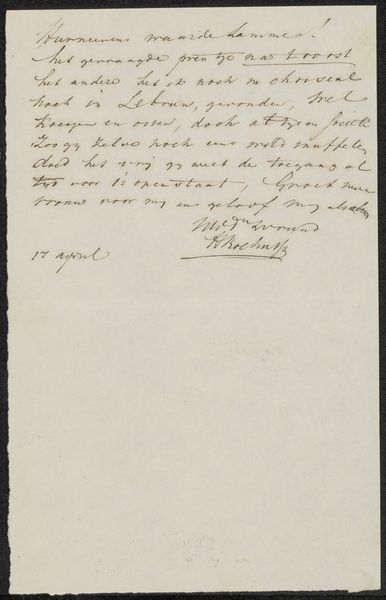

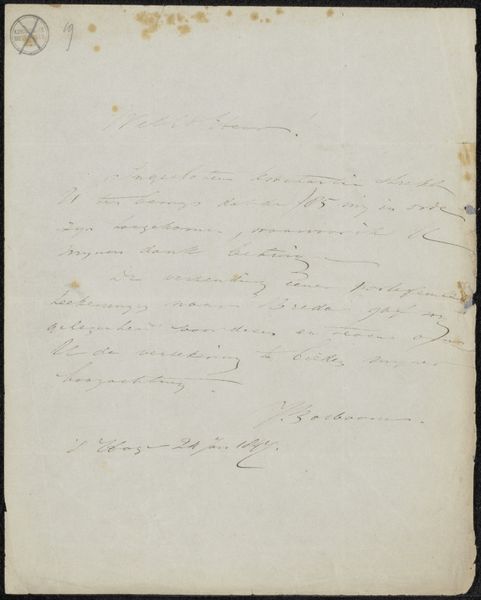

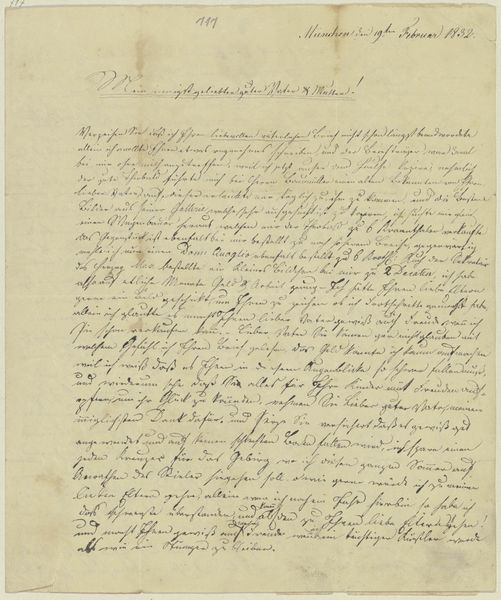

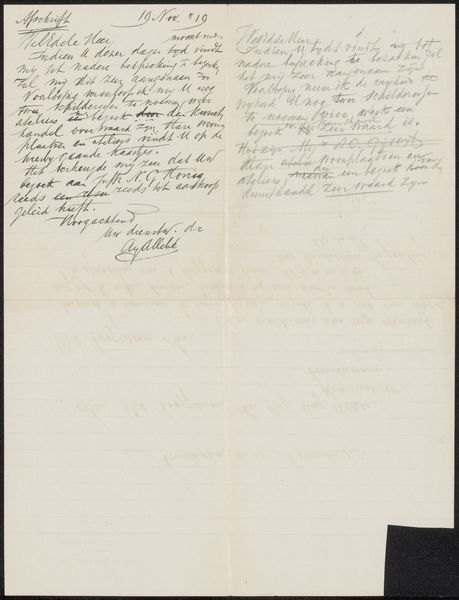

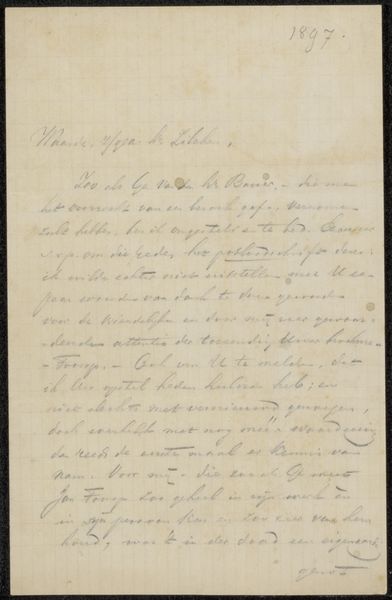

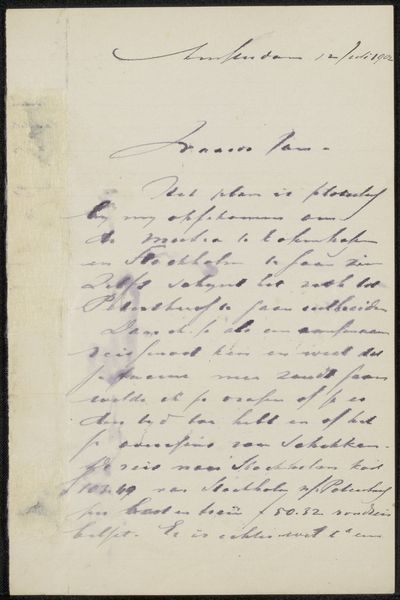

Curator: Here we have a letter entitled "Brief aan Fried. Gontard" by H.L. von Wintzigrode, thought to have been penned sometime between 1841 and 1843. It’s executed in ink on paper, a fine example of Romantic-era communication. What strikes you initially? Editor: It looks fragile, almost ghostly. The thin paper, the faded ink... It really evokes a sense of transience. The handwriting is beautiful though, very elegant, though at least one corner of the letter is unfortunately tattered. Curator: Indeed. The use of ink provides stark contrasts and tonal variation, all held together by the grid-like composition imposed by the writing itself. The text becomes texture, if you will, organized and considered on the rectangular picture plane. We should address, too, that there are more significant portions of the letter now lost. Editor: I'm thinking about what kind of ink they used back then, what that meant for its availability and cost, what quill was used, who this Wintzigrode might have been, and Fried. Gontard for that matter! A glimpse of Romanticism, sure, but also, a reminder of labor. Writing that neatly takes serious practice. Not just anyone could write a letter that reads like artwork itself. Curator: Precisely. The act of writing itself transforms a mundane object into one imbued with aesthetic significance. Observe the formal script, a kind of calligraphy, and consider how such mastery speaks to a broader visual culture. It’s about more than communication; it’s presentation, the art of the message itself, elevated by form. Editor: I’m more drawn to the social exchange here, this communication. Think of the paper being handmade, likely pulped rags by hand, treated, cut... Each touch mattered. It suggests a slowness, a deliberation we've mostly lost today, as much the act of making than just communicating. What does that suggest? Curator: That there are inherent visual components intertwined with functionality, of course! Both, in this example, converge within its materiality. The object itself, even fragmented as it now is, embodies aesthetic purpose. Editor: Maybe it embodies a social purpose first and foremost that then, only indirectly, provides aesthetic engagement, but each provides some food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.