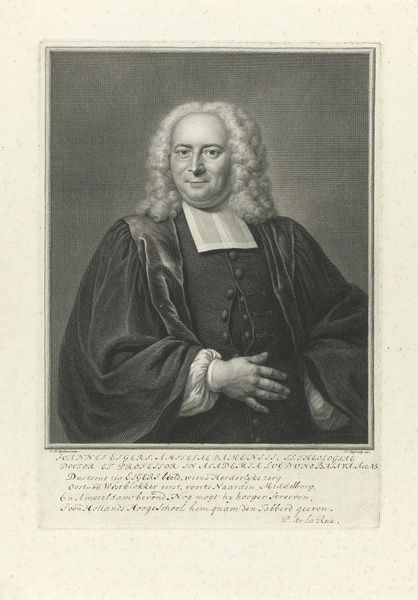

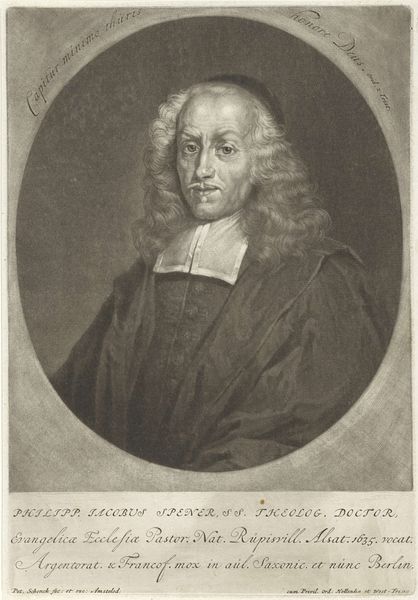

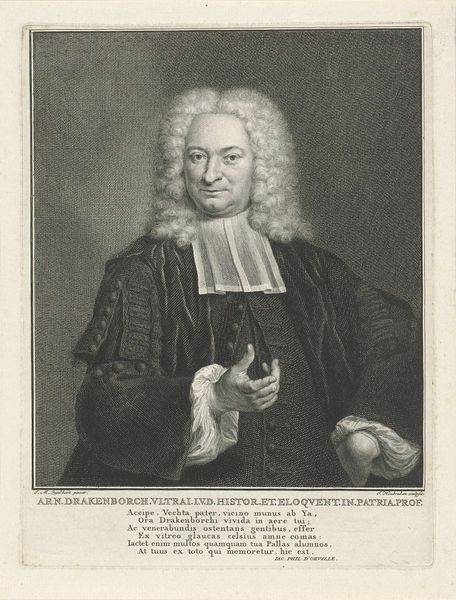

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 168 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

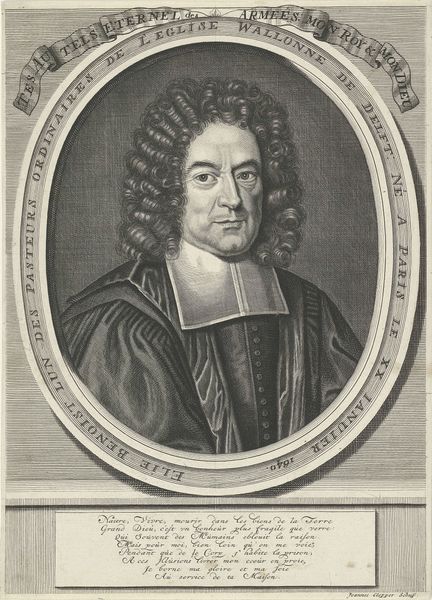

Curator: This is "Portrait of Augustus Johannes Buxtorfius" by Jacob Houbraken, created in 1745. The artwork, an engraving, is part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: The subject exudes such confident ease, and the texture in that cloak looks unbelievably rich and tactile for an engraving. Curator: It is striking, isn't it? As we situate this portrait in its historical moment, the Dutch Republic was undergoing a period of complex socio-political shifts. Portraiture became a powerful tool to express identity, class, and profession. Here, we see Pastor Buxtorfius presented with symbolic weight—his very image reinforces a social hierarchy of its time. Editor: I immediately wonder about Houbraken’s technique here. The engraving process—the cutting into the metal plate, the inking, the pressing—demands a skilled laborer. Look at the lines creating that cascading wig and the fabric’s sheen; they speak to the engraver’s material expertise. Was he celebrated as an artisan, or viewed as simply a reproducer of images for a wealthy elite? Curator: Houbraken was celebrated. He developed an international reputation based on engravings of portraits, many of which came from paintings. These allowed ideas from the enlightenment to spread, but often they were accessible to specific classes and further propagated systems of hierarchy. Note the detail—how Houbraken uses the limited tonal range of engraving to convey both texture and social status, emphasizing Buxtorfius’s position. Editor: The social implication behind the access of art is a topic for longer discussion, certainly, but coming back to that textural element of the image. This detail makes me want to analyze not just who is represented, but how the materials shaped the representation itself. What does it mean to portray wealth, status, through the relatively reproducible medium of engraving? It complicates the relationship between art, craft, and the societal structures they inhabit. Curator: This has given me fresh ideas, considering not just how Houbraken rendered Buxtorfius's image, but also how that very rendering comments on social identity and its distribution in 18th-century Dutch society. Editor: And I'm thinking about the physical act, the skilled labour needed to produce it, making the viewer aware of the labour necessary for cultural preservation. A lasting reminder, then, of what labor makes and unmakes in any portrait’s representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.