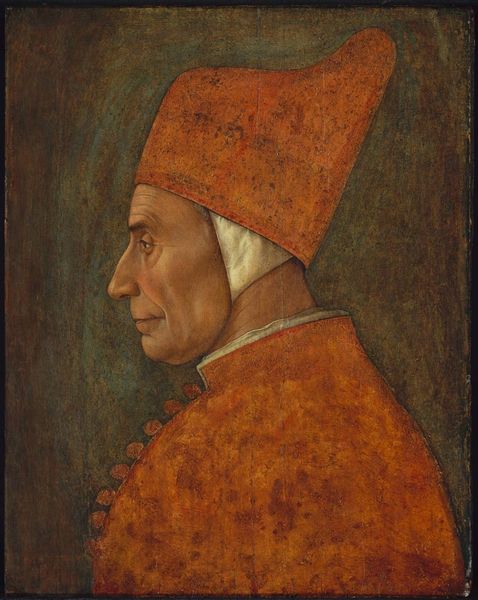

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

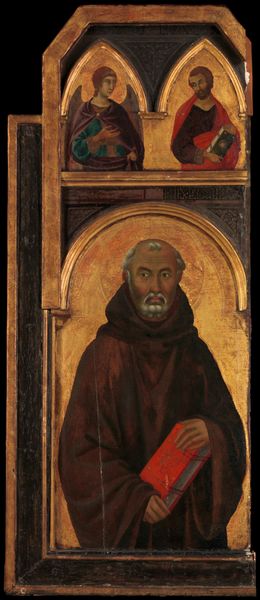

painting

#

oil-paint

#

history-painting

#

early-renaissance

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: Overall 9 7/8 x 7 3/8 in. (25.1 x 18.7 cm), with added strip of 3/4 in. (1.9 cm) at right

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is Hugo van der Goes’s “A Benedictine Monk,” likely completed between 1480 and 1483. The work is rendered in oil paint. Editor: Instantly, there’s such a contemplative sadness in his downturned gaze. He seems weighted, not by the earth, but by something intangible, something felt. Curator: The painting exemplifies the Early Renaissance style with its move toward realism, especially in rendering the human form, with light and shadow playing to model three-dimensionality, while hearkening back to a monochromatic presentation style, using oil for saturation rather than varied hue. Consider how this realism would have played against expectations and production standards of its era, what kinds of labor supported the realization of his image? Editor: Oh, totally. He isn't idealized—you can see the wrinkles, the weariness. But this makes him approachable in a strange way. I find myself wondering about the actual monk: Was he this serious? Did van der Goes exaggerate this melancholy, imbue the figure with a sense of pathos perhaps representative of broader societal tensions of the time? Curator: Exactly! Early Renaissance painters often walked this tightrope. And it's crucial to remember how the social conditions dictated what could be painted and how. Someone commissioned this, likely with very specific ideas about its function and reception. Van der Goes may have innovated with his technique and representational skills, but that experimentation happened within certain constraints, always impacted by those patrons and the institutions that gave meaning to works. The artist both pushed against those restrictions and needed their labor to succeed. Editor: I can imagine him now. Did the Monk's stoicism betray some world-weariness that the painter could immediately discern in the human figure. His skill brought their stories together for the eye to see across so much time. I love how portraits like this feel like tiny time machines! Curator: They certainly offer us insight into the social, economic, and religious values attached to representing people, but often, a patron with disposable wealth wanted a monument made in their honor. These paintings had specific intended audiences, from other elite citizens to, maybe, future generations of religious dependents. Editor: In looking into the future by reflecting upon an intimate present. Food for thought indeed. Curator: Agreed. Every painting is like a set of contracts negotiating aesthetics and cultural power, which ultimately determine how such a work lands here, now, for our considerations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.