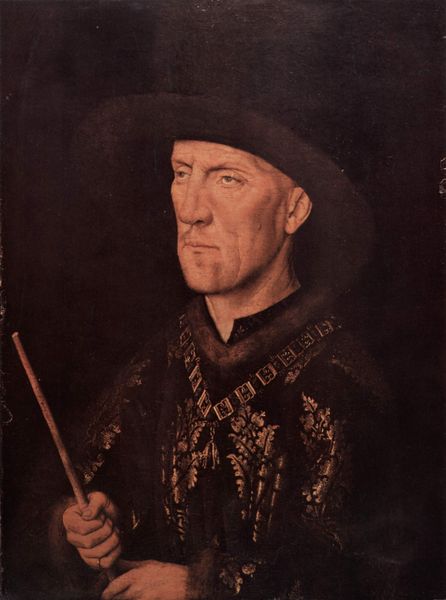

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

flemish

#

academic-art

#

early-renaissance

Dimensions: Overall 12 x 8 1/2 in. (30.5 x 21.6 cm); painted surface 11 5/8 x 8 1/8 in. (29.5 x 20.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Dieric Bouts’ "Portrait of a Man," dating from around 1465 to 1475, greets us with a study in restrained power. It’s currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the smoothness of the surface, almost like enamel. There’s an arresting calmness here, but I find it a little cold, a little… distant. Curator: That sense of distance might stem from the meticulous detail – observe how each plane of his face seems carefully constructed. There’s a feeling that we're seeing an idealized, almost symbolic, representation of the individual, not necessarily a completely naturalistic portrayal. His hands clasped together symbolize piety, or perhaps humility. The man's gaze averted may symbolize discretion. Editor: I see that too. The material qualities – the way the oil paint is layered so precisely - speak to the increasing status of painting at this time. It’s not just about religious icons anymore, it’s about capturing and conveying wealth, status, and skill. Look at the crisp lines defining that hat, it wasn't about expressing emotion, more about display of craftsmanship, isn't it? Curator: Partly, yes. But I would also argue that even this level of meticulousness conveys a specific meaning. Consider the Early Renaissance focus on capturing likeness as a virtue; it demonstrates respect and attention. Bouts carefully captures not just what he sees, but also an essence, which links him to the Northern Renaissance ideals of portraying both outer and inner truth. Editor: I'm drawn to what his clothing would have represented at the time; the finery suggests merchant class prosperity beginning to grow. I also wonder about the social impact on how Bouts even learned these methods and secured commissions; patronage during that period enabled artists like Bouts to dedicate a lifetime honing technique. The act of painting itself reflects a shift towards material comforts. Curator: Yes, patronage was undeniably pivotal. To that end, understanding the symbols woven within adds to its lasting appeal; the subject's averted gaze, coupled with the prayerful hands, signals virtuous contemplation for viewers then, while raising unanswered questions about the subject's personal story for us now. Editor: In the end, analyzing both its physical qualities, and what resources, wealth, and power was needed for the artwork's existence is really the best path to insight. The details are incredible here, showing the beginning of consumerism displayed in the craft, and the craft itself becoming something of status and high regard. Curator: Perhaps, we find then an equilibrium—a convergence of artistry, symbolism and society revealing much more than just an individual portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.