painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

byzantine-art

#

medieval

#

painting

#

book

#

oil-paint

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

men

#

history-painting

#

portrait art

#

statue

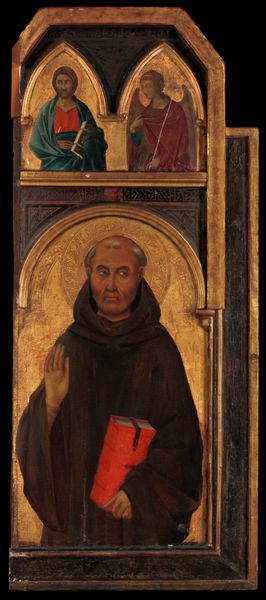

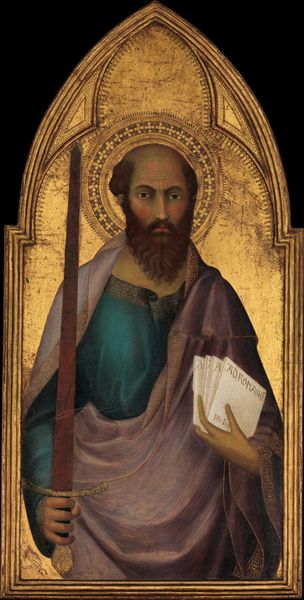

Dimensions: Overall, with framing elements, 49 x 20 7/8 in. (124.5 x 53 cm); Saint Benedict, painted surface 27 7/8 x 16 in. (70.8 x 40.6 cm); pinnacle, painted surface 10 1/4 x 15 3/8 in. (26 x 39.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This panel, depicting Saint Benedict, was created in the 1320s by Segna di Buonaventura, an Italian painter working in the Sienese tradition. You can find it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your initial take? Editor: Hmm, immediately I’m struck by how…grounded he feels, despite the gold leaf background. Almost earthy, with that deep brown robe against the shiny, celestial gold. Makes me think he’s a saint for the everyday person, somehow. Curator: Precisely! Benedictine monasticism, even then, emphasized practical living, labor, and learning. Consider the period: fourteenth-century Italy, rife with political and social unrest, but also a flowering of religious fervor. How might Benedict’s representation here respond to those anxieties? Editor: Well, that bright red book certainly stands out! Is it his to-do list? Seriously though, it is the Rule of Saint Benedict, right? Maybe it’s a reminder that even amidst chaos, there’s a structured path to find some meaning. Curator: The book certainly signifies his authorship of the Rule. But notice also his direct gaze. Segna presents him as a figure of authority, not in the sense of worldly power, but spiritual strength rooted in his teachings, challenging existing hierarchies. The placement of other holy figures also reinforces a cosmic connection. Editor: I hadn’t noticed the angel and what looks like another saint at the top! They seem tucked away, almost like celestial footnotes. But the way Saint Benedict holds that book, with those rough hands…he seems completely present, focused. Like, “Yeah, divinity’s great, but let’s get to work.” Curator: The physicality you describe reflects an artistic tension prevalent in the Sienese school. On one hand, a continued adherence to Byzantine conventions—the gold ground, hieratic representation—while on the other, an emerging naturalism and humanism, giving us access to his psychological dimension. Editor: It's like a visual conversation, isn't it? The artist pulling from both heaven and earth to paint Saint Benedict. So, this monk holding this shiny red book manages to bridge some kind of gap between divine order and the messy human experience. That’s pretty powerful. Curator: Indeed. This image of Saint Benedict provides a powerful intersection of spiritual aspiration and practical wisdom for the medieval viewer, but it provides for the modern viewer a window into this same dichotomy and intersection, one which still haunts us today. Editor: A reminder that we can find guidance in a good book and perhaps within ourselves? I like it! Time well spent.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.