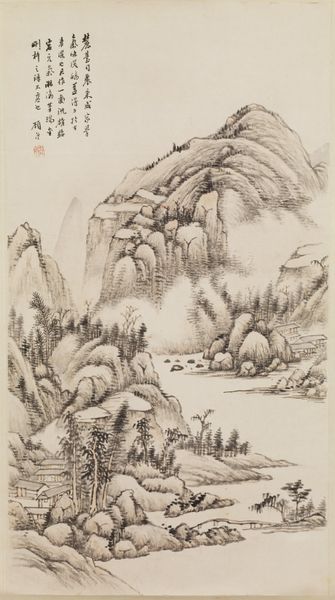

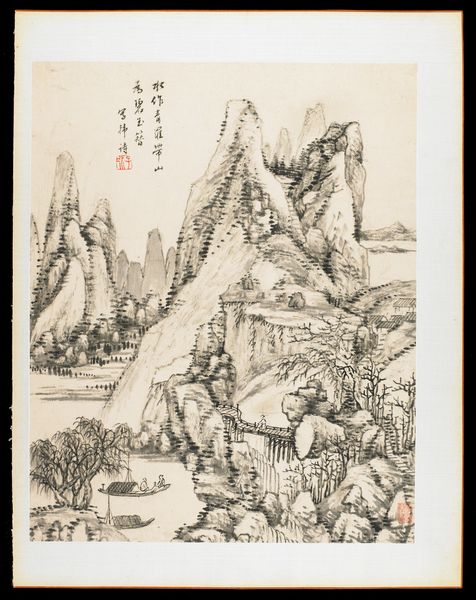

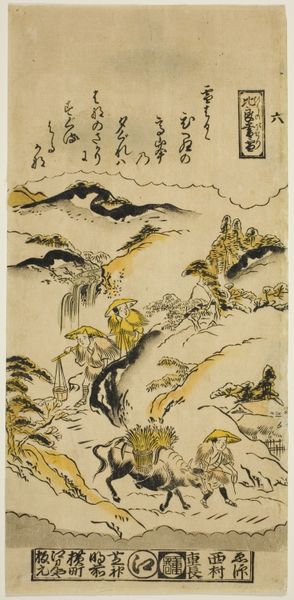

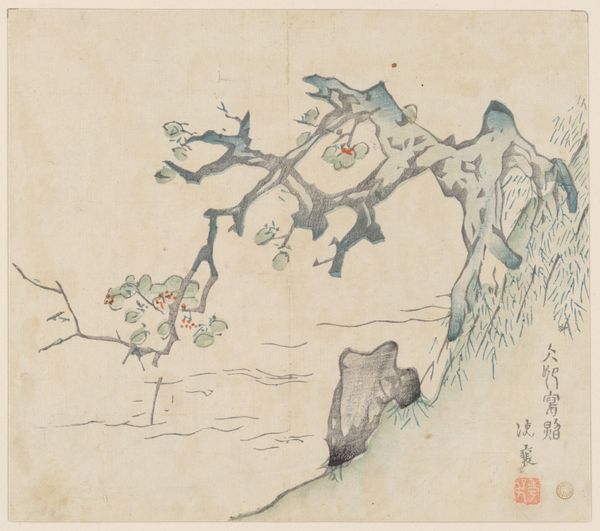

drawing, tempera, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

ink painting

#

tempera

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphy

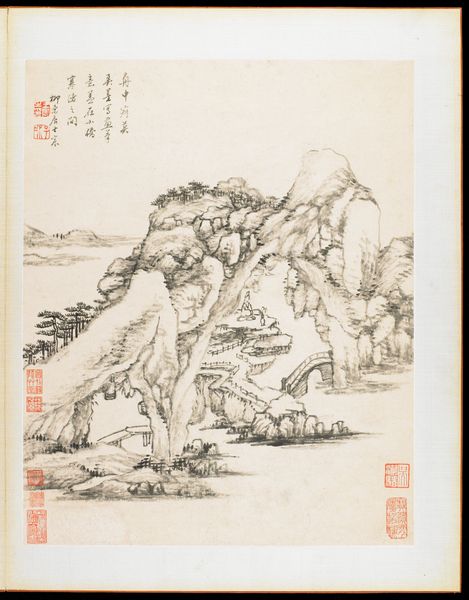

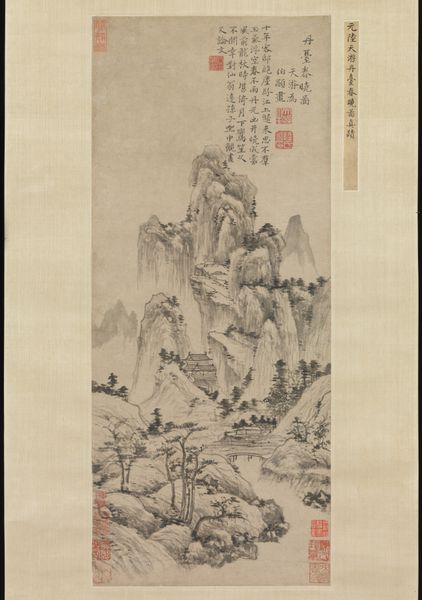

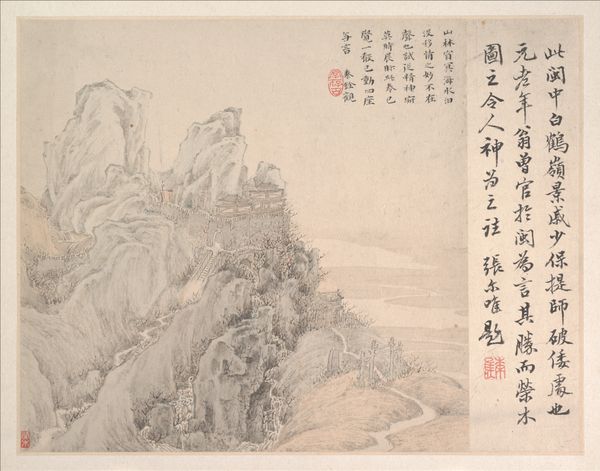

Dimensions: 16 7/16 x 13 3/16 in. (41.75 x 33.5 cm) (image)19 3/4 x 15 5/16 in. (50.17 x 38.89 cm) (leaf, overall)19 15/16 x 15 15/16 x 1 1/4 in. (50.6 x 40.5 x 3.2 cm) (entire album, overall, closed)

Copyright: Public Domain

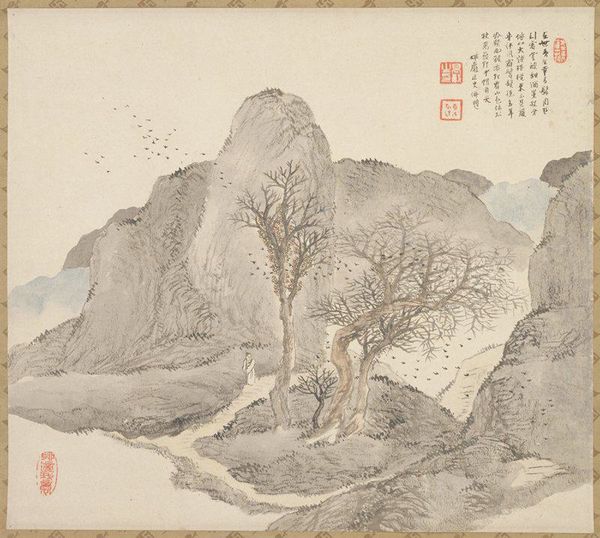

Curator: Editor: Here we have Wang Chen's "Album Leaf," created in 1774, using ink and tempera on paper. The landscape depicted has a dreamlike quality. What aspects of its creation strike you most? Curator: Looking at this, I'm immediately drawn to the labor embedded in both the creation of the paper itself and the application of ink. Consider the material conditions necessary for Wang Chen to even conceive of this work – the forestry, the processing, the distribution networks that put the paper in his hand. Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn't really thought about the socio-economic systems that enabled it. How does that lens change our view? Curator: It invites us to question traditional hierarchies. We often elevate the "artist" as a singular genius, but this piece is the product of collective labor. What does this say about value, authorship, and even the definition of 'art' itself? Are the unseen hands that prepared the materials not also artists? Editor: That's a great point. Seeing it as a product of collective labour makes it even richer. The textures, too, created using ink with what I'm assuming are a mix of techniques: the sharp strokes of the calligraphy against the softer washes of the mountain. Curator: Exactly. How does that contrast in textures mirror the social stratification we just discussed? Could it represent a visual tension between intellectual and manual labor? Editor: It certainly feels intentional. This deeper consideration of the material and social factors at play makes the image so much more engaging than just seeing the peaceful mountain scenery at first glance. Curator: Precisely. By examining the means of production, we dismantle the notion of art existing in a vacuum, revealing it as a product deeply embedded in its historical and social context. Editor: Thank you. Considering the making enriches the work! I am going to carry these thoughts with me.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

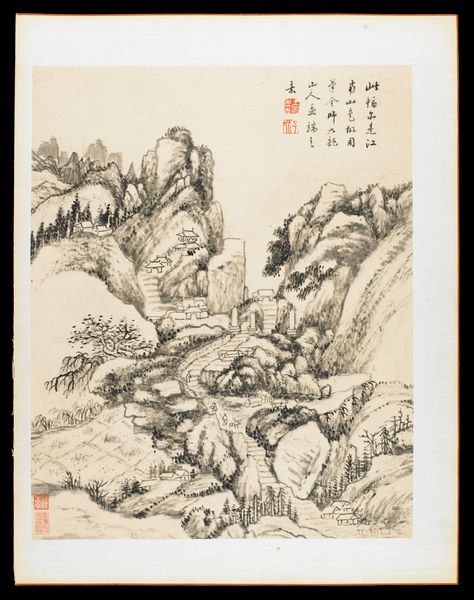

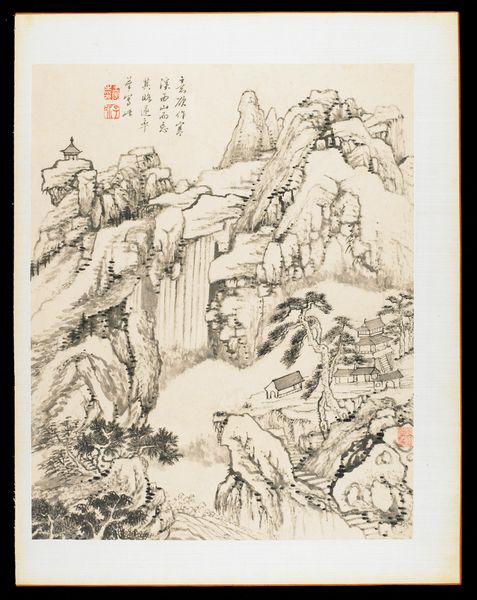

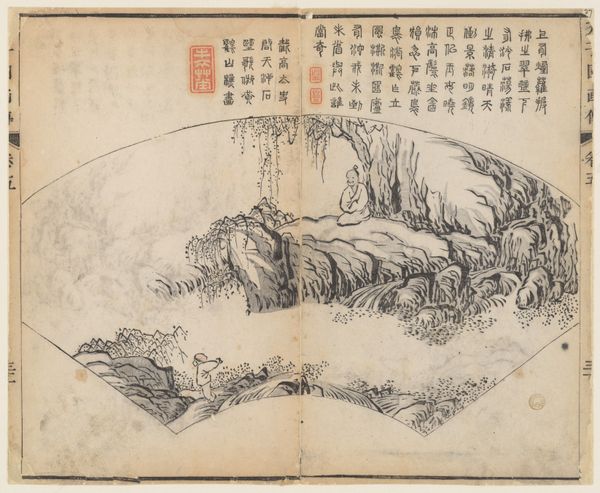

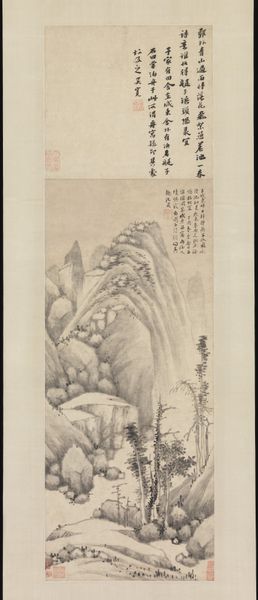

Born in Kiangsu province, Wang Ch'en was a descendant of the great literatus Wang Shih-min and a great grandson of the artist Wang Yuan-ch'i. He served for a while in the Grand Secretariat and as a prefect in Hunan province. Wang's illustrious family heritage strengthened his reputation as an orthodox painter and he is one of the so-called Four Minor Wangs of the later Ch'ing. Wang's inscriptions here indicate that the basis for this album of large landscapes was the natural scenery of Ch'u, a Warring States (480-221 BCE) kingdom located south of the Yangtze River. In 1774, Wang was serving as a low-level official in this region. His inscriptions also mention earlier poets and painters whose conceptual and stylistic influences along with natural scenery inspired the various scenes here, which were based on sketches made at the sites themselves. The inscriptions read: 1) The landscape of Ch'u is extremely scenic. I came across one place and sketched it but neglected to ask its name. 2) One morning I entered the sea in search of Li Po; looking in vain among the paintings of mere mortals for the "Immortal of Ink." 3) The ceremonial burial mounds and Szechuan are neat. This is a scene of entering the gorge. 4) I have used the brushwork of Shu-ming (Wang Meng) to paint the style of Old Man Sung-hsueh (Chao Meng-fu). There is resemblance because they are from the same family.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.