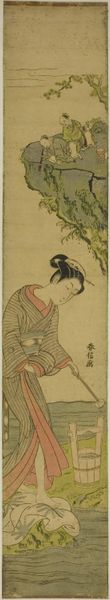

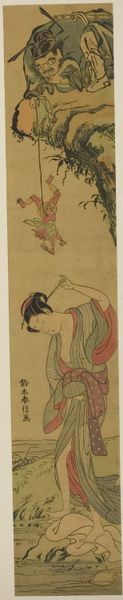

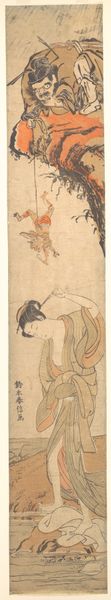

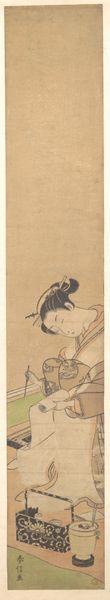

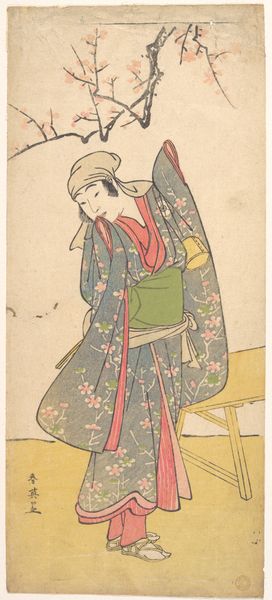

Daoist Immortals Spying on a Young Beauty c. 1768

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

orientalism

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: At first glance, this evokes a very voyeuristic and uneasy feeling. The image is divided. The earth tones are so subdued, I almost missed the figures lurking above! Editor: This is "Daoist Immortals Spying on a Young Beauty," a woodblock print crafted around 1768 by Suzuki Harunobu. Harunobu was a master of ukiyo-e prints. The vertical format, called a "pillar print", adds to the dynamic of looking up to the immortal observers. Curator: Indeed. What about the act of woodblock printing itself? We're seeing the product of multiple skilled artisans collaborating; from the artist, to the carver, to the printer. The subtle gradations of color, particularly in the woman's kimono, suggest a complex layering process, right? This wasn't simply a mass produced commodity. Editor: Exactly! Consider the socio-political undercurrent here too. Harunobu’s works frequently featured courtesans and everyday life in the pleasure districts of Edo. By depicting the gaze of Daoist Immortals, the artwork critiques hierarchical power structures within Japanese society. In many ways, this is a conversation on the objectification and moral judgements women experienced then and now. Curator: It makes one question consumption, too. Who was meant to purchase and display this? The smooth surface, the controlled lines. There's refinement here that speaks to a patron with discerning tastes and available capital. Ukiyo-e served a broader demographic, yet specific markers signal its engagement with upper classes. Editor: Right, we have to remember the context: The Tokugawa Shogunate's rigid social hierarchy restricted merchants, who became some of ukiyo-e's most ardent patrons, from overt displays of wealth. Prints like these, that often portrayed Kabuki actors and scenes from Yoshiwara pleasure quarters, provided a veiled critique of that rigid structure and celebrated the pleasures that were repressed. It provided the merchant class with a means of culturally performing defiance within the boundaries of the permissible. Curator: That friction is visually palpable. The almost casual presentation of labor contrasts strongly with an opulent suggestion that wealth facilitated leisure for many depicted in Ukiyo-e pieces. This adds extra dimensions to a seemingly serene waterside tableau. Editor: Indeed, reflecting upon these artworks means looking into the cultural narratives that influence not just our reading of it, but our reality as well. Curator: It has really challenged me to re-think the construction, use, and appeal of these images. I find it unsettling but technically remarkable.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.