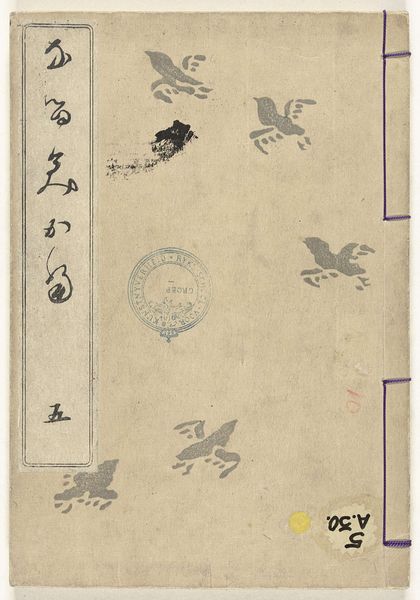

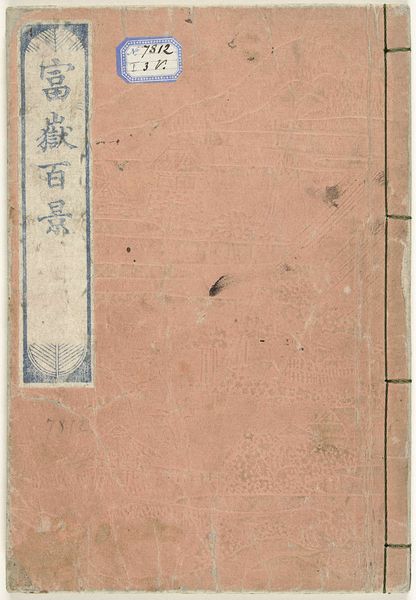

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 157 mm, height 135 mm, width 390 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

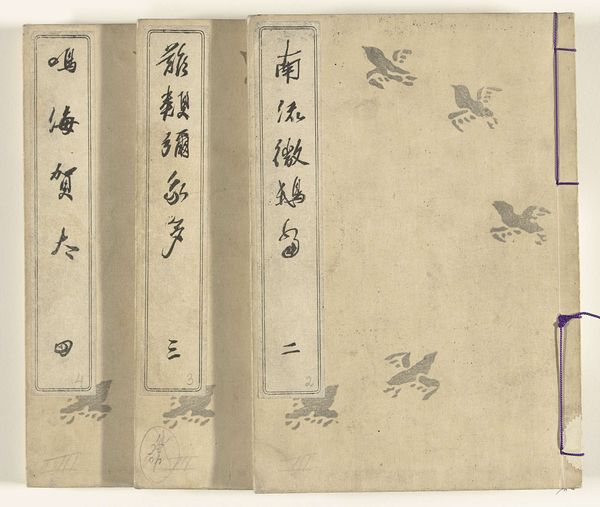

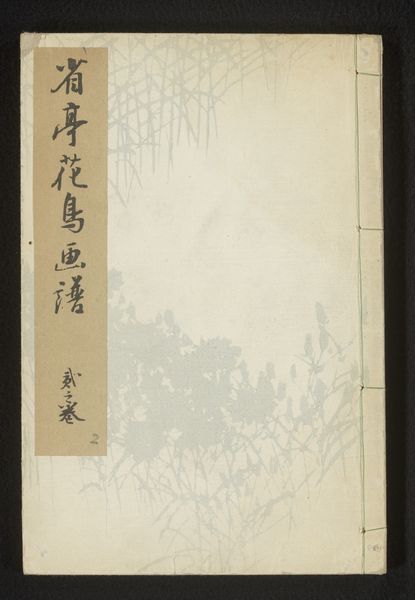

Curator: So, here we have "Narumi Fabric Patterns, Part Two" by Odagiri Shunko, created in 1883. It’s an example of Ukiyo-e, executed as a drawing and print with ink on paper. Editor: It has such a delicate, almost ghostly feel to it. The stylized birds, scattered across the surface, seem to float against the aged paper. Is it a textile design sample? Curator: Precisely. This piece resided within a larger pattern book, displaying designs that would have been directly applied to fabrics. Editor: Thinking about this being a pattern for textiles makes me consider who would have had access to these designs. The clothing and other textiles crafted from this period had profound implications on class and power, right? Curator: Absolutely. Textiles during the Meiji Era reflected the rapid social and political shifts. There was a complex negotiation between embracing Western industrialization and maintaining Japanese artistic traditions. Publications such as these offered templates, bridging tradition and progress. The Ukiyo-e style allowed artisans to depict familiar images within a more current consumer context. Editor: And there is something quite potent about the mass-reproducibility of printed textiles, making them available to a broader spectrum of the population, therefore influencing trends and societal aesthetics. But the tension between high art and craft is something I keep coming back to, the labor that goes into the original artwork being then reinterpreted and, in a sense, disseminated. Curator: Right. Examining who profits from and is credited for artistic endeavors is fundamental. During this period, many female artisans involved in textile production may not have received recognition, yet their expertise shaped aesthetic landscapes. The pattern books contributed to aesthetic access, but it also reinforces a stratified system within the cultural industry. Editor: Exactly. It’s in the cross-section of utility, art, identity, labor and cultural narrative that something like this becomes intensely fascinating. These fabric patterns served the needs of daily life and can offer rich, intersectional insights. Curator: I concur. Viewing “Narumi Fabric Patterns, Part Two” enables us to dissect the layers of meaning inherent within functional objects, questioning historical power dynamics in cultural production and dissemination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.