engraving

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 214 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

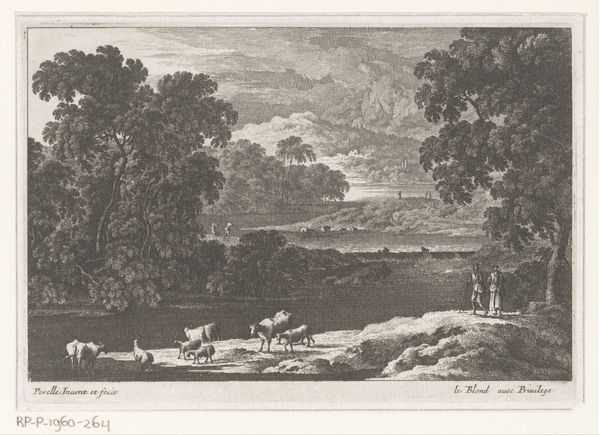

Curator: Before us hangs Nicolas Perelle’s “Landschap met rivier en wandelaars,” a baroque engraving likely created sometime between 1644 and 1695. What catches your eye first? Editor: The trees. It's how the engraver suggests volume with lines—that shivering density makes them feel like restless masses holding back some powerful weather, but actually created with metal tools on a flat sheet! It reminds me how reliant we were, once upon a time, on artisanal craft to share art through reproductions, before the age of mechanical processes. Curator: Indeed! There is a powerful push and pull between nature and civilization, suggested here in how humans traverse and coexist in this rendered wild. There are also suggestions of artifice—note the imposing architecture nestled amidst all this. Almost like something you see in Claude Lorrain, though, the natural features feel untamed. Editor: It speaks of landscape transformed into consumable commodity. Note how people were the object in early photographic works, standing stock-still while landscape painters were at work for the wealthy who traveled to experience nature from a position of dominance and privilege? Curator: Absolutely. Though here I'm struck by how small they are in the composition—not lording over, just within, contemplating and being part of something much grander. In its fine detail I imagine the engraver spending long hours. A sort of devotional attention. I am interested, though, if we can assume all were experiencing the wild as the engraver would imagine it, too, as something beyond any human capacity or hubris. Editor: Of course not. Look how controlled the composition really is—all leading to an inevitable vista. It reinforces ideas about who can access such views. Who the art is made for, and by, through the mastery and marketing of prints like this, destined for specific collecting markets. Curator: So while you focus on the physical aspects of the artwork and production methods in that market of consumers—for whom images of the Dutch landscape could be consumed like chocolate, shall we say? —I experience, I think, something more from this detailed rendering. Its evocation, perhaps, of our place inside and also beyond nature's scale, and with no control, whatsoever. Editor: I agree on that aspect of scale and sense of presence! Seeing and analyzing art in terms of tangible history is where it makes its power apparent to those who engage its ideas of craft and the consumer cultures around them, even centuries after its creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.