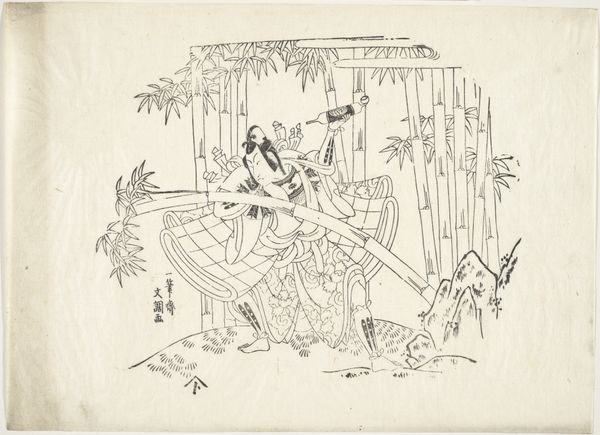

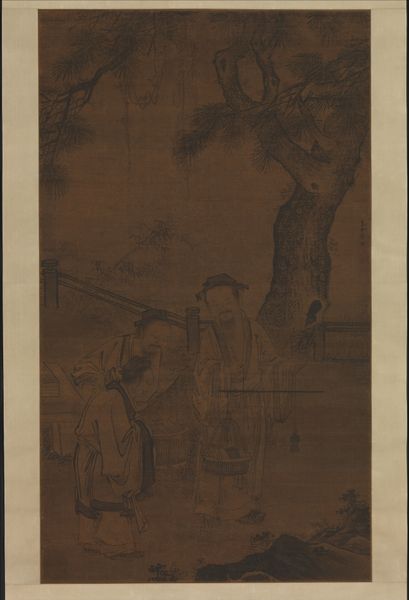

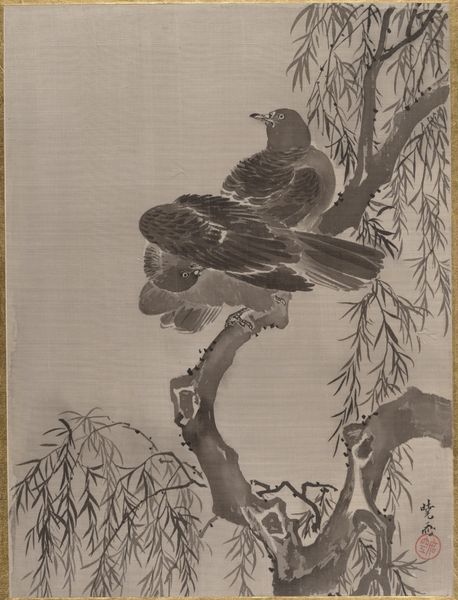

drawing, ink

#

portrait

#

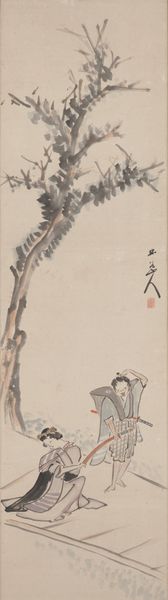

drawing

#

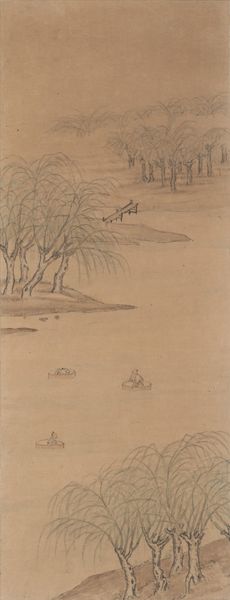

ink drawing

#

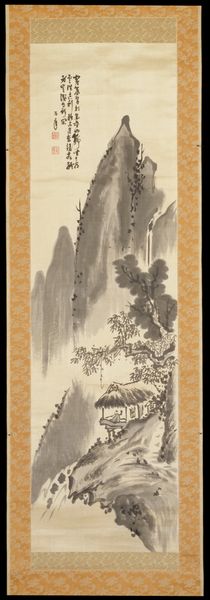

ink painting

#

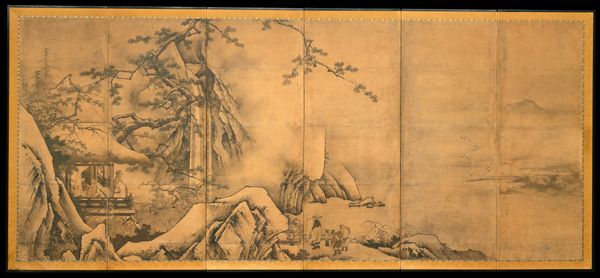

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

ink

Dimensions: Image: 52 1/2 in. × 21 in. (133.4 × 53.3 cm) Overall with mounting: 80 × 25 3/16 in. (203.2 × 64 cm) Overall with knobs: 80 × 27 1/4 in. (203.2 × 69.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Well, this feels like stepping into a dream. The wispy, inky washes... it's both serene and slightly unsettling. Editor: This ink drawing, "Tōkaibō with a Fishing Basket", was created by Soga Shōhaku sometime between 1758 and 1778. Shōhaku was a fascinating figure, known for his eccentric personality and somewhat unconventional approach to traditional Japanese painting. You can find this piece right here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curator: Unconventional is right! Look at the way he renders the figure's face, almost cartoonish. The exaggerated smile and wrinkles…is that supposed to be… wisdom? Or something else? Editor: I think that ambiguity is precisely the point. The figure depicted is likely Tōkaibō, a semi-legendary wandering monk known for his Buddhist devotion, albeit an unconventional one. The fishing basket would signify self-sufficiency, a turning away from society to connect to nature. It speaks to the social turmoil of the Edo period and this artist’s yearning for alternatives to the status quo. Curator: The bamboo is significant here as well, no? A symbol of resilience and flexibility… but rendered so wildly. The strokes are almost violent in their energy, belying bamboo's typical gentle connotations. It makes me wonder about the artist's personal struggles, a questioning of established cultural narratives maybe? Editor: It’s certainly a work steeped in cultural symbolism, ripe for reinterpretation. We also have to remember Shōhaku's artistic lineage; while he rejected certain aspects of the Kano school of painting, his mastery of ink wash techniques is undeniable. The monochromatic palette focuses the viewer's attention on line and form. Curator: True. There's a psychological weight, too. The face stares out, almost directly, but also seems lost within itself. What do you think draws us to these kinds of figures throughout art history? Always questioning... always at the margins... Editor: Perhaps because they represent the tension between individual desire and social constraint – a tension as relevant today as it was then. Shōhaku used the art to process these political sentiments. Curator: Yes, well, this image lingers long after you look away from it, doesn’t it? Editor: It makes me consider how rebellion can be manifested, through the seemingly benign symbol of a basket or an unconventional brushstroke.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.