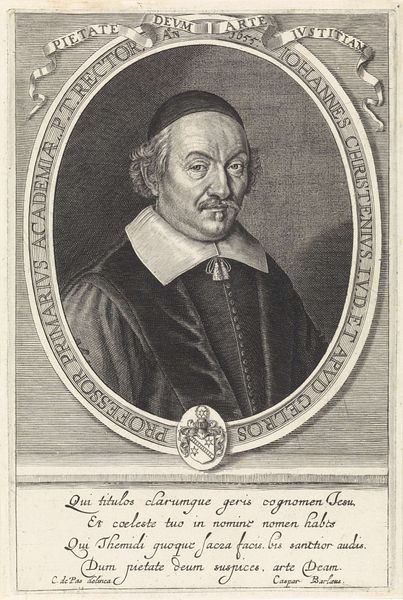

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 317 mm, width 203 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

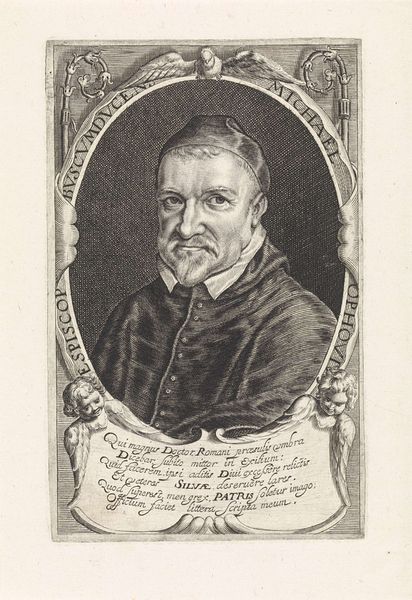

Curator: This is a portrait of Jacob Boonen, Archbishop of Mechelen, created in 1633 by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. It’s an engraving, held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, there’s a certain somber weight to this piece. The shading is so finely done, giving the portrait depth, despite being just black and white. You can feel the gravitas of the subject. Curator: Well, Jacob Boonen held a very significant position in the Catholic Church during a turbulent time. That weight, as you put it, is probably deliberate. See how the artist positions him within the oval frame, almost like a reliquary? And the ornate curtain in the background adds to the sense of importance and ritual. Editor: Speaking of that background and framing, consider the incredible labor involved. All those precisely etched lines on the archbishop’s clothing, on the curtain behind him, and on the ornate frame holding the portrait…an army of artisans certainly had a hand in its crafting and printing. Curator: Yes, engravings allowed for the wide distribution of images. This image likely circulated within religious and political circles, reinforcing Boonen’s authority through its symbolism. Editor: What I find fascinating is the contrast: on one hand, mass production for influence, and on the other, this intricate labor involved with engraving the image to allow that replication. What’s your take? Curator: I see the material labor going into its construction almost a deliberate signifier of legitimacy. Boonen’s position wasn't just spiritual, but deeply entangled with the material realities of power and influence, hence its rendering in the graphic form of an engraving. It is almost like he himself has become an icon—an instantly recognizable image invested with cultural memory. Editor: The craft and sheer skill involved in the printmaking elevate him beyond a simple likeness; it emphasizes how printed matter was consumed. Curator: Yes, so this engraving tells us just as much about its reception and consumption as it does about the subject’s likeness, offering unique insight to religious imagery of the 17th Century. Editor: Well, by examining the work involved we gain new understanding of art of the period, even for the consumption and politics associated.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.