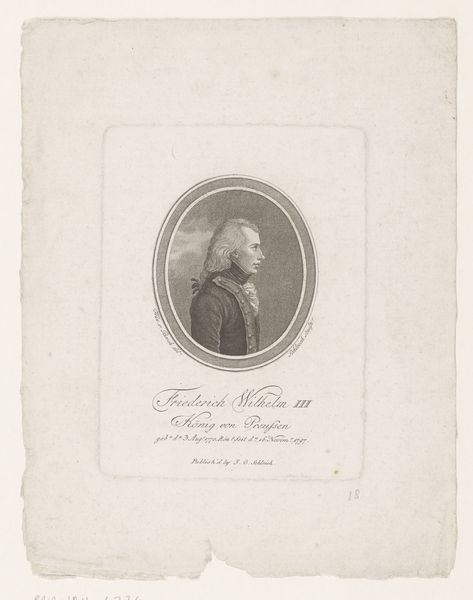

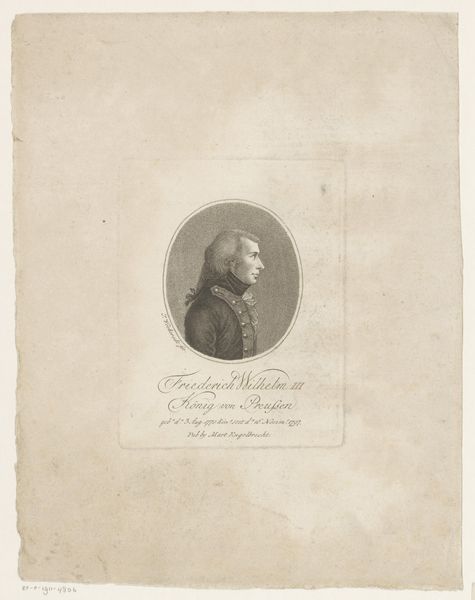

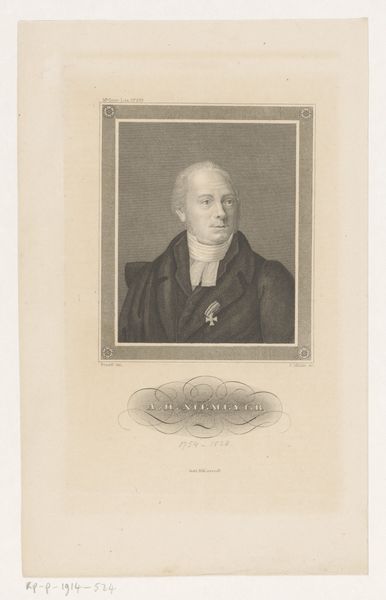

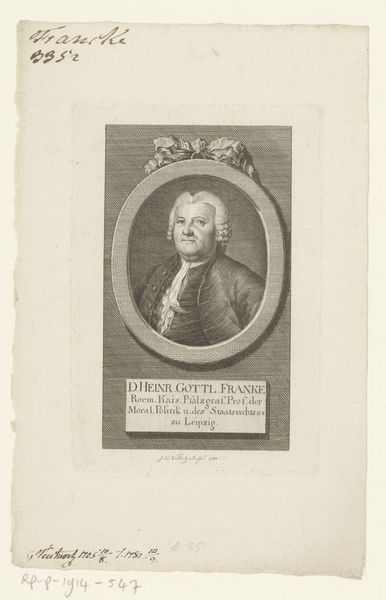

print, engraving

#

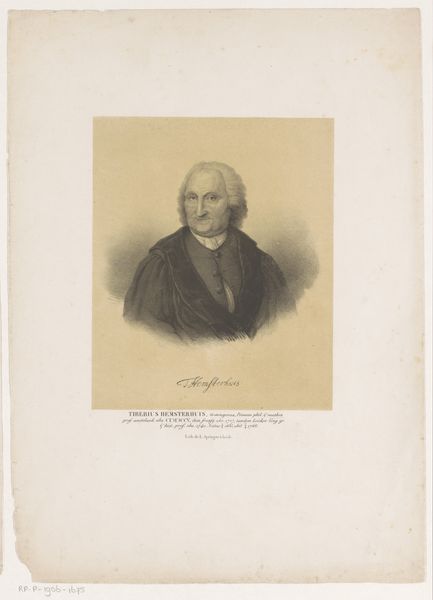

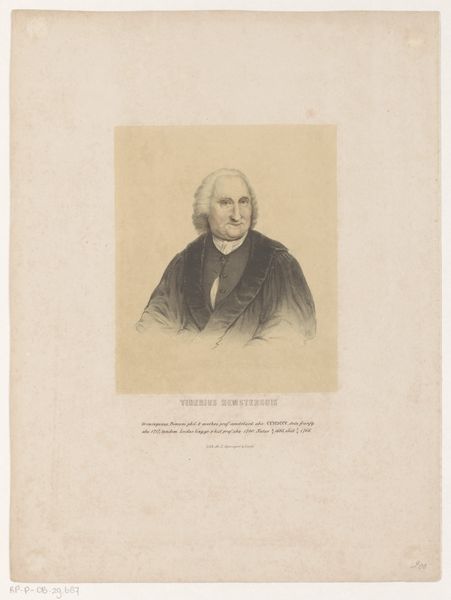

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 227 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Editor: This is a print, an engraving actually, titled "Portret van Georg Tobias Christoph Fronmüller," made sometime between 1822 and 1850 by Christoph Veit Schellhorn. The portrait has an austere feeling to it. It’s so formal. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see the representation of power and societal expectations embedded within a Neoclassical aesthetic. It's an era wrestling with revolution, yet clinging to order and established hierarchies, and portraits such as these served to reinforce the status quo. Do you notice how the subject, presumably a person of influence, is framed within an oval, almost like a classical cameo? Editor: Yes, now that you mention it, the framing *does* feel significant. Does that choice echo anything about his role or the intended audience of the print? Curator: Absolutely. The oval format lends itself to the idealization typical of that era, reminiscent of ancient Roman busts, associating the sitter with virtues like reason and civic duty. This particular rendering also subtly reinforces religious authority by imbuing the sitter with a kind of quiet stoicism. Editor: So, it’s about presenting him in a certain light – to convey a particular message to those viewing it. Curator: Precisely. By engaging with visual conventions and disseminating widely via print, these images shaped public perception, but also tell us about class and social expectations of the time. Consider the historical backdrop; how might power relations have played out for various groups in society at this time? Editor: That’s a really interesting way to think about portraiture! I was mainly looking at it as a static representation, but understanding its context really unlocks so much more. Curator: Indeed. Examining art through an intersectional lens unveils the intricate power dynamics that helped shape historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.