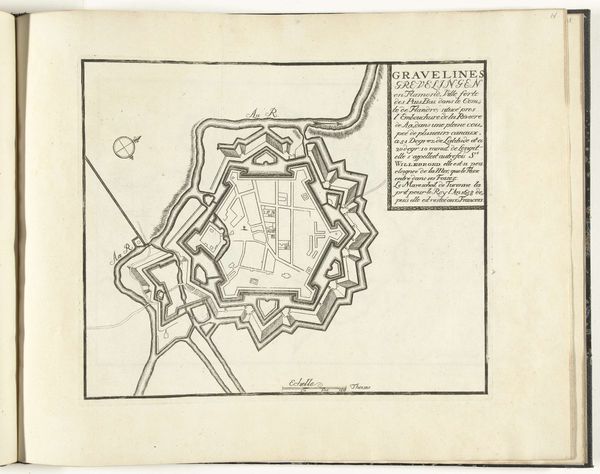

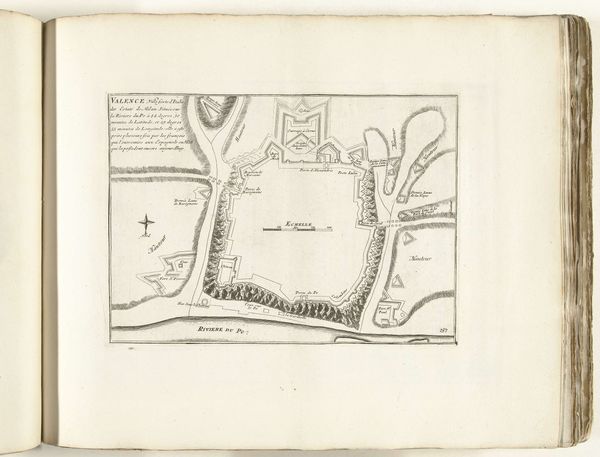

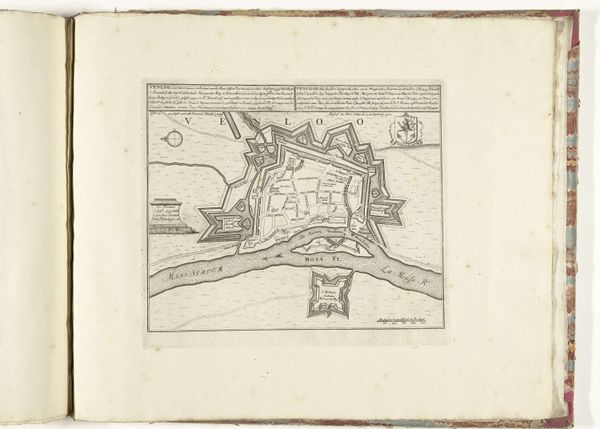

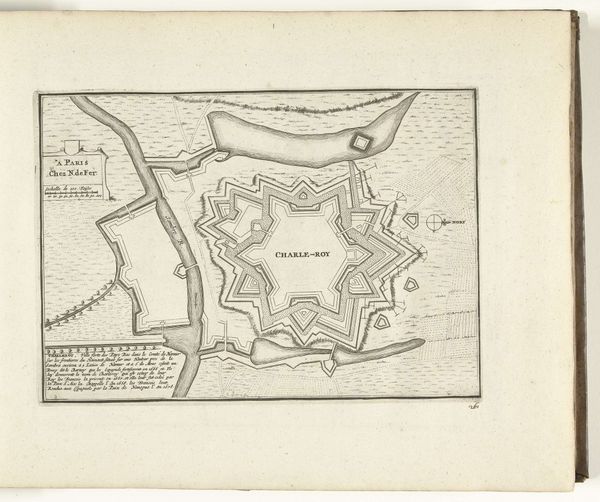

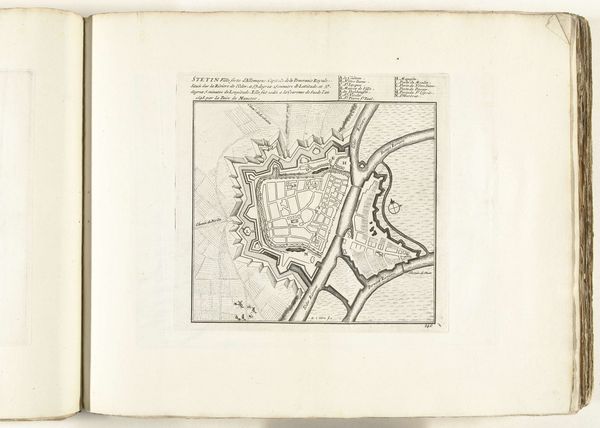

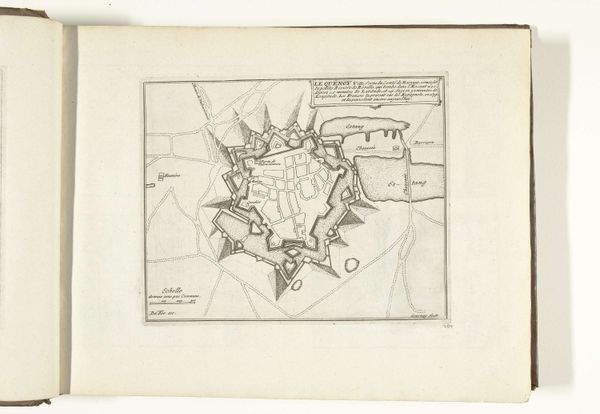

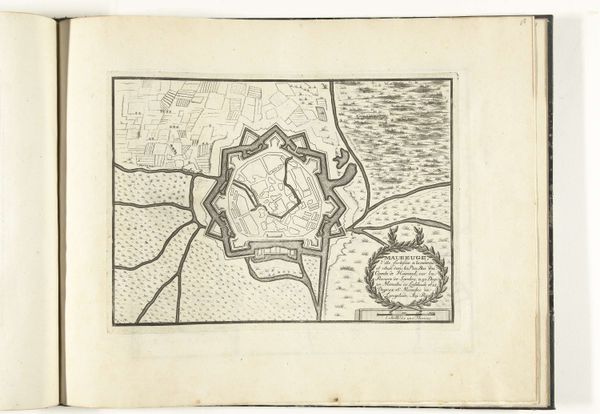

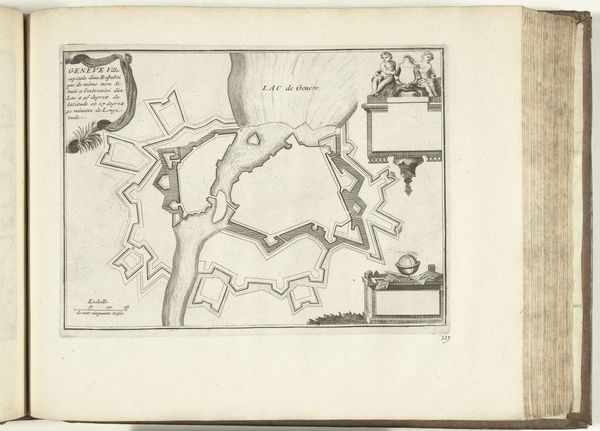

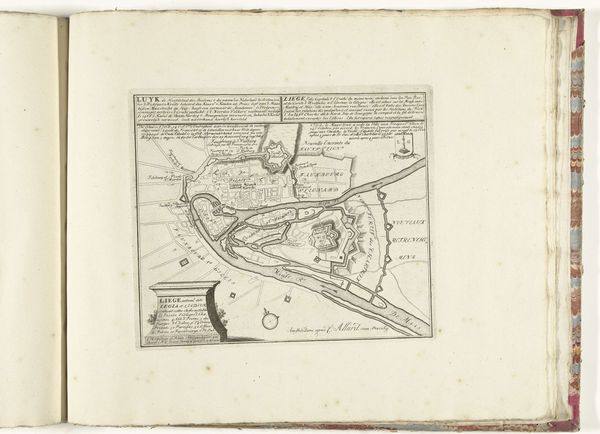

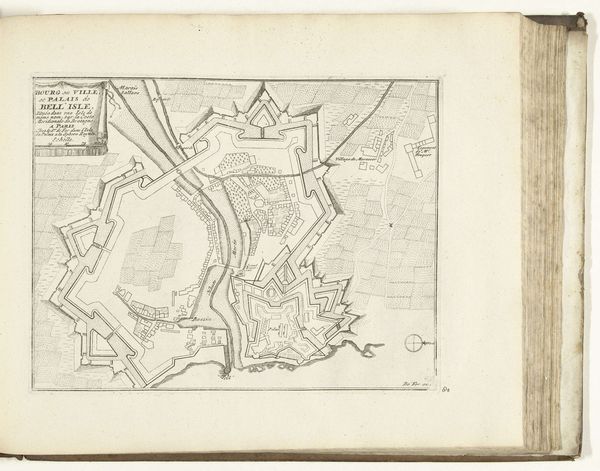

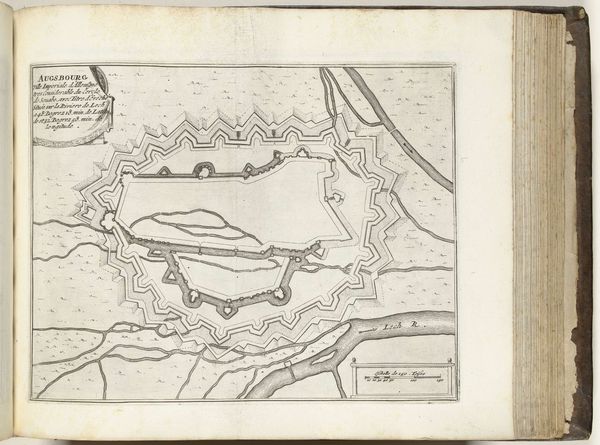

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 182 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This detailed city plan is titled "Plattegrond van Jülich, 1726." It's an engraving, executed in ink on paper, by an anonymous artist and currently resides in the Rijksmuseum. The composition itself is dominated by geometrical forms, isn't it? Editor: Absolutely, my first impression is of its severe geometry. It's a stark, almost unsettling order imposed upon what would have been organic chaos. One immediately notices the centrality of the fortified citadel and how the layout maximizes defensibility. Curator: Precisely. The city is depicted with incredible precision, showcasing the baroque era's fascination with order and control. We see intricate lines denoting buildings, streets, and waterways. The engraver’s skill is quite evident. Think about the intense labour required to produce this. Editor: Yes, let's think more about that labor. What's particularly fascinating is to consider the process – the initial surveying, the crafting of the plate, and then the physical act of printing. I also imagine its consumption and intended impact. Curator: Intriguing! Let’s zoom in on its semiotics. Note how the walls create defined boundaries, physically and conceptually. It presents the town of Jülich not merely as a physical space but as an emblem of power and protection. What symbolic implications might the repeated geometric shapes have? Editor: I am wondering about accessibility and the production cost of creating these. In a way, isn't the act of mapping, through ink and paper, an exertion of power in itself? Claiming land and codifying the territory through this sort of print medium also speaks to something grander – the rise of the state. Curator: Certainly! The detail reinforces a sense of authority and meticulous planning. But how do we reconcile the stark utility of this urban layout with what the people who actually lived in it felt? Were the consumers really served by it, or just forced to fall in line? Editor: True, Jülich would have been so different on the ground, lived as experience. These maps could be seen as tools both to survey a space and alienate people from a land they had laboured to inhabit, separating inhabitants from lived realities. The cold precision perhaps lacks a sense of daily life. Curator: Yes, this print transcends its practical purpose, emerging as a visual manifestation of societal values of the 18th century. It certainly does bring many exciting issues up for debate! Editor: A fascinating collision of geometry and social practice. I have learned a lot more about both.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.