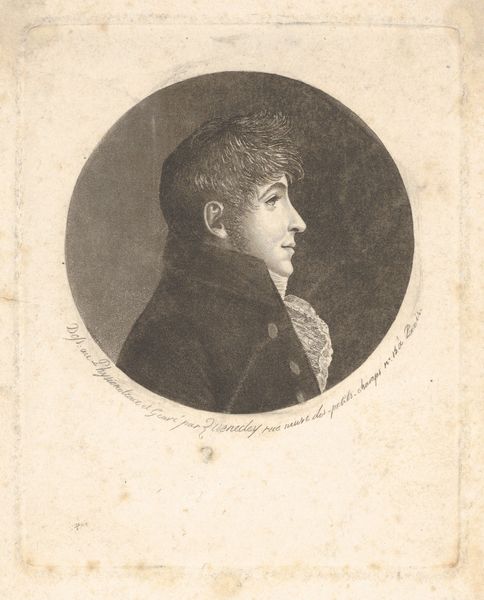

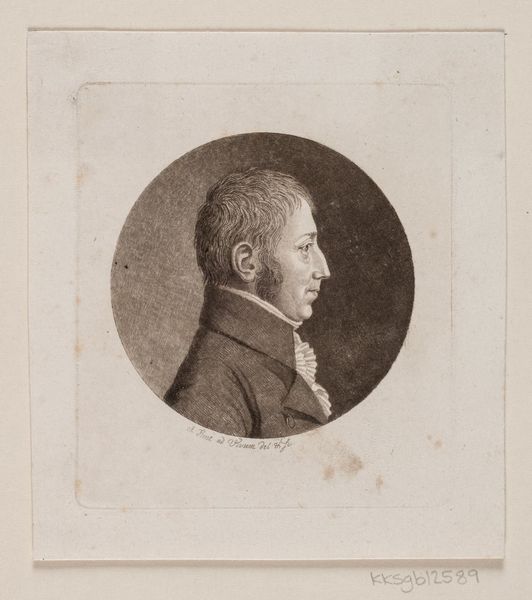

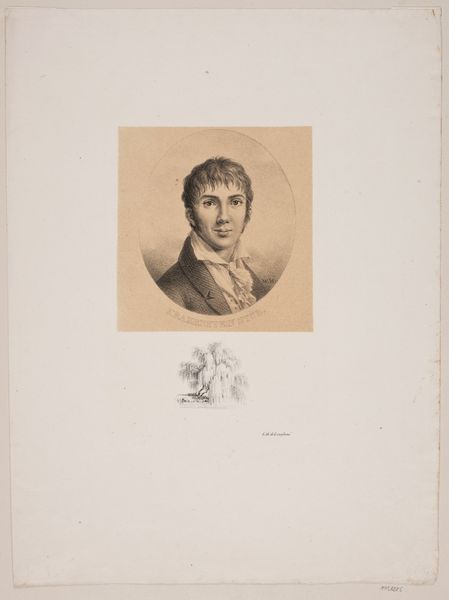

drawing, print, paper, pencil, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

engraving

Dimensions: 63 mm (None) (billedmaal), 94 mm (height) x 72 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This is Andreas Flint's portrait of M.L. Nathanson, dating roughly from between 1767 and 1824, currently held here at the SMK. The piece is rendered with pencil and engraving on paper, creating a very delicate and refined image. Editor: It certainly gives that impression. There's a tight circular structure housing the figure, and it appears to restrain him somehow—despite the open collar, it feels rather controlled and austere. Curator: Restraint is a fascinating observation, particularly when considered alongside Nathanson's social standing as a prominent member of Copenhagen’s Jewish community. Portraits during this period were frequently deployed as tools for social navigation, signaling integration, aspiration, or sometimes even resistance to dominant norms. Do you think that the use of monochrome speaks to such restraint? Editor: Possibly, though I’m struck by the textural contrast achieved within this monochromatic framework. The smoothness of the face, rendered with the soft give of pencil, sits against the patterned background and clothing, suggesting subtle levels of status. And look at the precise hatching used to build form—volume rises from the page thanks to Flint’s command of tonal variation and linear definition. Curator: Exactly, and this is a society built upon such visual indicators. A prominent individual like Nathanson navigates in a climate where religious identity and societal expectations were frequently in tension. The engraving work allows for widespread reproduction. What impact does that have? Editor: Wide dissemination would surely aim to establish an ideal. It suggests a controlled image projected into the world: reason and purpose expressed formally. This reinforces an ideological reading, but one needs to consider the effect that material reality imposes on the artwork. Curator: Of course. By examining the portrait within a wider context—taking into account Nathanson's identity, the socio-political backdrop, and the material processes involved in creating and distributing his image—we are able to interpret both the intentionality of the portrait and its engagement within various cultural power dynamics. Editor: And the aesthetic result is the expression of that tension as a compelling interplay of shadow, light, texture, and form. I notice, on repeated inspection, that interplay anew. Curator: Thank you, yes, by placing emphasis on identity and its intersectionality with the more historical aspects of the piece we surface so many interpretations. Editor: And I remain attentive to the way that such meaning emerges out of form.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.