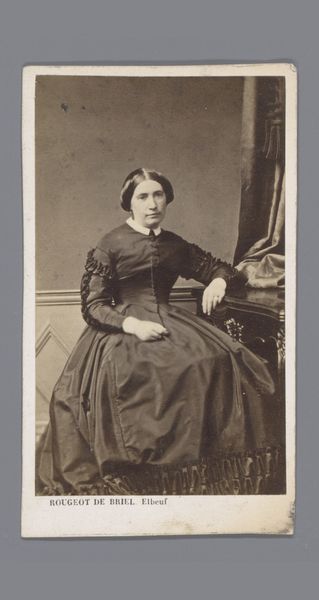

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this portrait, I immediately sense a certain gravity, wouldn't you agree? There's a quiet stillness to her pose and expression. Editor: Absolutely. And this is "Portret van een vrouw," or Portrait of a Woman, by A. Böeseken, created around 1865. It’s a gelatin-silver print, a fairly common medium for photographic portraits at the time. The material itself provides a unique insight. Curator: The materiality really speaks to me; think of the process of creating a gelatin-silver print at that time. Each step—the preparation of the glass plate, the development process—required specialized knowledge, almost an artisanal skill. It emphasizes the labor involved. Editor: It does place this object firmly in a social context. Photographic studios were becoming more common, offering portraiture to a growing middle class. How did these studios shape identities, how did the sitting and display practices evolve through the cultural institutions? Curator: The level of craft contrasts with our contemporary mass-produced, disposable imagery. Consider the textile—the dress seems almost weighty and somber. We have the dark fabric but also trim. Each visual aspect has to have meant something socially and to the family involved. It represents labor in creating materials and a certain level of capital investment on her and her family's part. Editor: Precisely. The choice of clothing, the accessories, even the pose, all contribute to a constructed identity—a deliberate performance for the camera, and, more importantly, for posterity and a very precise presentation of social position and selfhood. The institutions dictated what was displayed publicly and how. Curator: Thinking of it from that perspective is key. It connects back to her relationship with societal norms in an interesting manner, as do the materials of the object itself. Editor: Indeed. And reflecting on those norms, one appreciates how much the simple act of commissioning a portrait represented at the time. Curator: This makes us question what materials and visuality we invest in today and for what purposes!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.