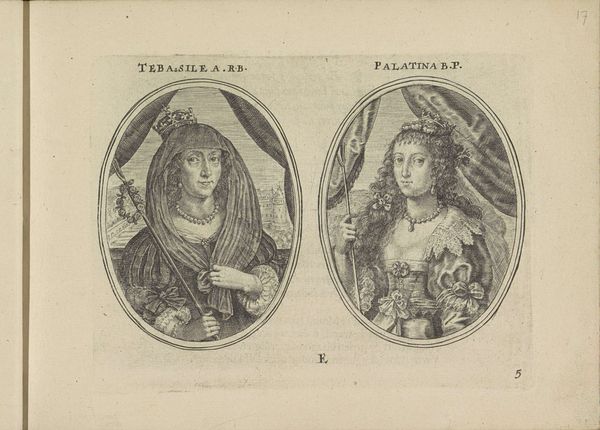

Portretten van Henriette Maria van Engeland en Christina van Zweden, beiden als herderin 1640

0:00

0:00

crispijnvandeiipasse

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 106 mm, width 152 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a print from 1640 by Crispijn van de Passe II, entitled “Portraits of Henrietta Maria of England and Christina of Sweden, both as shepherdesses,” currently at the Rijksmuseum. The two women appear in ovals. It strikes me as interesting that powerful queens are shown playing such simple roles, each holding a shepherd's staff and flowers. How should we interpret the representation of royal women in this idealized way? Curator: That's a great starting point. The shepherdess was a common trope in courtly love poetry and pastoral dramas of the time. It allowed aristocratic women to perform an idealized, innocent femininity. But I think it’s vital to consider how that performance intersects with real political power. Editor: In what way? Curator: Well, who are these women? Henrietta Maria, the Queen consort of England, was a deeply unpopular figure because of her Catholic faith and influence over her husband, King Charles I. Christina of Sweden was known for her intellect and later for her abdication and conversion to Catholicism. Both of these women challenged traditional gender roles in some respects, although one more publicly than the other. Consider how the image presents them. Do they appear conventionally submissive, despite the trappings of pastoral innocence? Or, in embodying this idealized role, do they indirectly assert a degree of control over their own image and, by extension, their political standing? Editor: I see what you mean. Maybe it's not about simple innocence, but about carefully constructed personas for political purposes. The idea of a queen adopting a disguise makes this portrait very different, a carefully crafted propaganda even. Curator: Exactly! Consider also how printmaking functioned as a tool for disseminating these constructed images across Europe. It begs the question, how did audiences interpret them, and how effective were these staged portrayals in shaping public perception of these influential, but ultimately controversial, women? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t thought about the active role these women might have played in creating and controlling their image through this pastoral allegory. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure. It shows us how even seemingly straightforward images are loaded with complex historical and political contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.