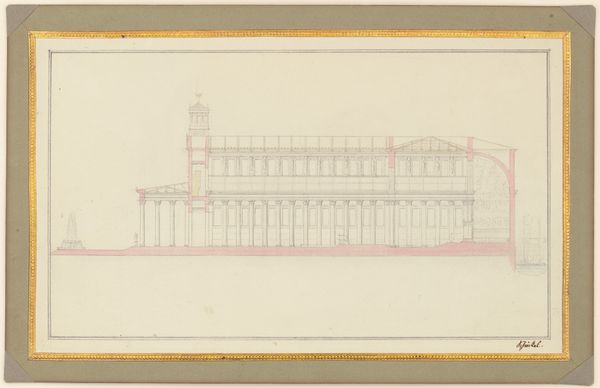

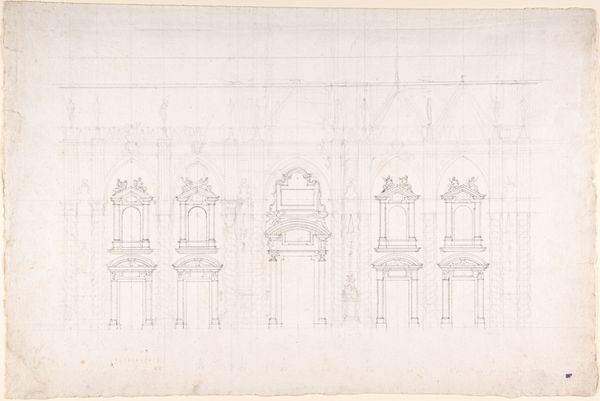

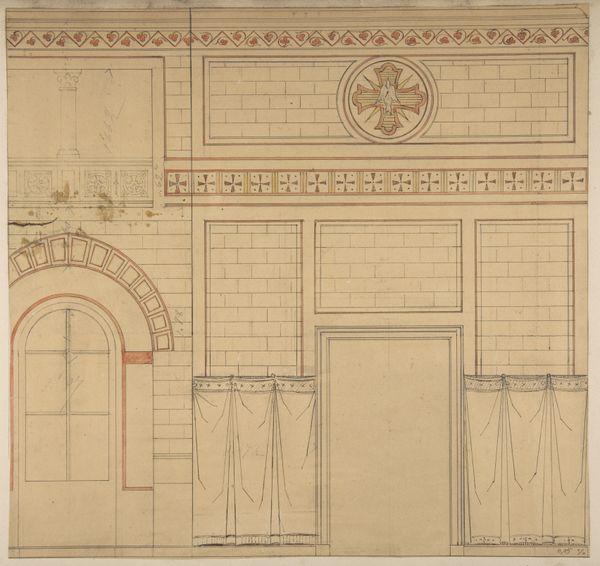

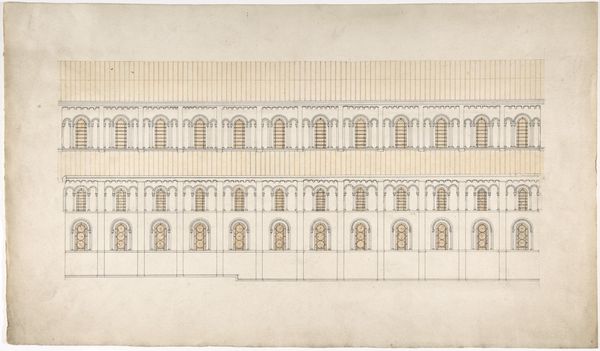

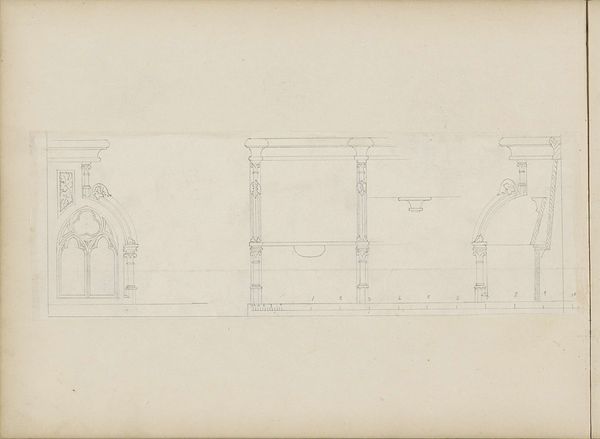

Section of the Crossing and the West End of a Cathedral for Berlin 1827

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil

#

architectural drawing

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 15.6 x 26 cm (6 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.) image: 14.2 x 24.7 cm (5 9/16 x 9 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the architectural ambition in this piece; even as a sketch it speaks to immense scale and authority. Editor: Indeed. What we're seeing here is a work by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, "Section of the Crossing and the West End of a Cathedral for Berlin," created around 1827. It's a drawing, primarily pencil, detailing a Neoclassical vision for a cathedral. Curator: The symbolism is powerful. The cathedral, of course, represents not just spiritual power, but also, especially in the 19th century, a form of cultural and political dominance. The scale is overwhelming, meant to inspire awe, and obedience, wouldn't you say? Editor: Absolutely. Think about the political and social context. Berlin was emerging as a major European capital, and architecture was seen as a tool for nation-building. The design, with its symmetry and classical elements, evokes a sense of order and control reflecting a society steeped in hierarchies of class, gender, and access. Who has the power to commission such buildings? Who is excluded from its symbolic message? Curator: The towers, echoing classical forms, hint at aspiration – reaching for something beyond the earthly realm, of course, but also staking claim, literally and figuratively, on the landscape. But the rigid Neoclassical lines also bring to mind how historical canons can often stifle more fluid, diverse architectural expression. Editor: I can see that. I see in it too the cultural memory that buildings hold – cathedrals especially represent a visual lineage connecting present to past, and perhaps trying to claim continuity to further a specific narrative of legitimacy. The inclusion of classical motifs strengthens this argument of legitimate imperial succession. Curator: Yes, it speaks to the use of history as justification. It's interesting to consider who this grandeur serves and who it silences in its imposing shadow. The artist himself, positioned as a product of the bourgeoise, no doubt saw in this architectural form a reflection of and projection into the societal order in which his livelihood thrived. Editor: Examining symbols, the sheer symmetry hints at this era's ambition to impose order. It highlights an aesthetic that valued clarity above the complicated realities on which power actually operated, almost acting like a tool for manipulating memory and consolidating authority. Curator: Thinking about its impact, it underscores how architecture both shapes and is shaped by our beliefs and power structures. It’s also just, well, a compelling architectural idea. Editor: I agree. It pushes me to consider buildings less as inert structures and more as sites where identities, politics, and history intertwine and influence one another.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.