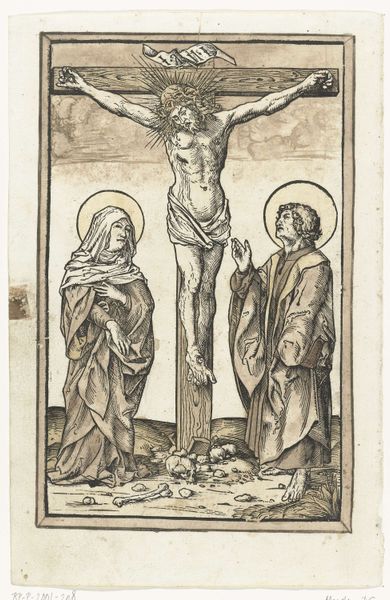

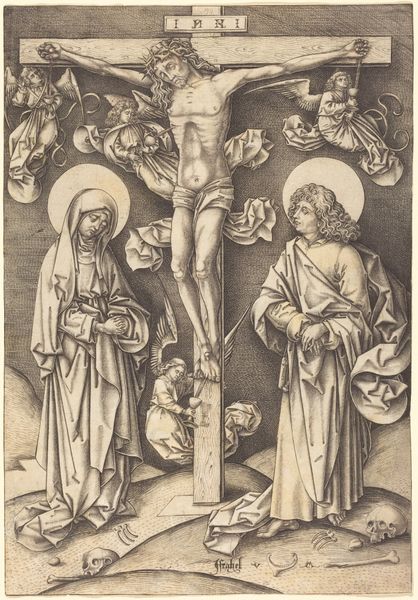

drawing, print, intaglio, ink, engraving

drawing

ink drawing

medieval

narrative-art

pen drawing

intaglio

figuration

ink

crucifixion

history-painting

northern-renaissance

engraving

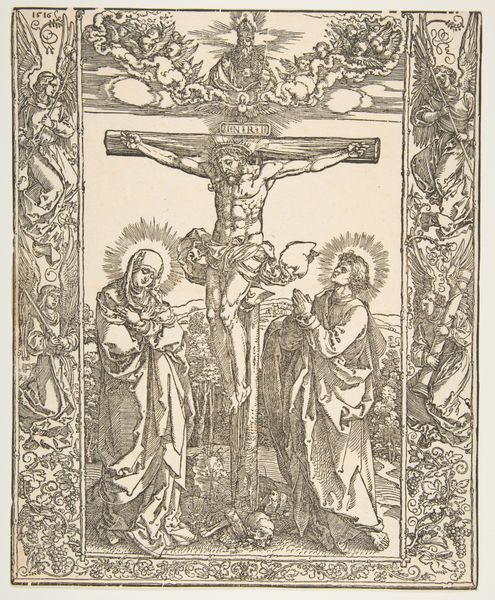

Dimensions: sheet: 11 1/2 x 8 3/16 in. (29.2 x 20.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look closely at this engraving; it’s called *The Crucifixion,* made in 1521 by an artist known only as the Monogrammist G.Z.. It’s currently held here at The Met. Editor: Well, right off the bat, it's intense. That stark black ink against the white paper makes the whole scene feel... theatrical. A real drama playing out. Curator: The starkness is partially inherent to the engraving technique, carving the image into a metal plate. Think of it as the Northern Renaissance playing with a kind of dramatic chiaroscuro, a way of using light and shadow to amplify emotion. Editor: And amplify it does! The figures, especially Christ, are so detailed and... muscular. There’s a raw physicality here that gets under your skin. And that skull at the base of the cross…heavy symbolism, naturally. Curator: Indeed. The skull represents Adam, signifying Christ's sacrifice as redemption for humanity's original sin. This print likely circulated widely, as a portable devotional object for personal contemplation. Editor: I find the framing incredibly striking. All these intricate patterns that almost soften the edges, drawing you inward to that stark central image. It's like the world, in all its ornate complexity, gives way to this raw, singular moment. Curator: The border certainly contributes to that effect. It isolates the central scene while still being very much a part of the image. I'm also fascinated by how G.Z. utilizes linear perspective in such a complex setting. See how the artist navigates the crowds around the main subject through foreshortening? Editor: It’s strange how beauty and horror combine here. Makes you think about how suffering is often presented to us. Polished, refined, packaged, even…but still packs a visceral punch. Curator: Absolutely. This image offered early 16th-century viewers an intimate glimpse into one of the central events in Christianity. A memento mori but also an affirmation of hope. Editor: You know, stepping back, it’s pretty incredible that an artist working 500 years ago can still conjure these emotions today. That is the power of images. Curator: Indeed. It encourages us to reconsider how our public and private spheres interact. Something to remember on the way to our next encounter.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.