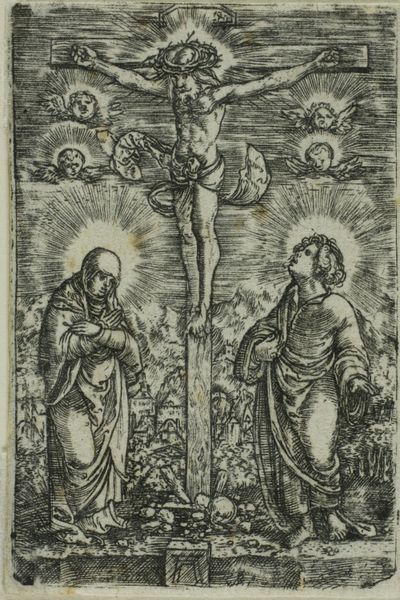

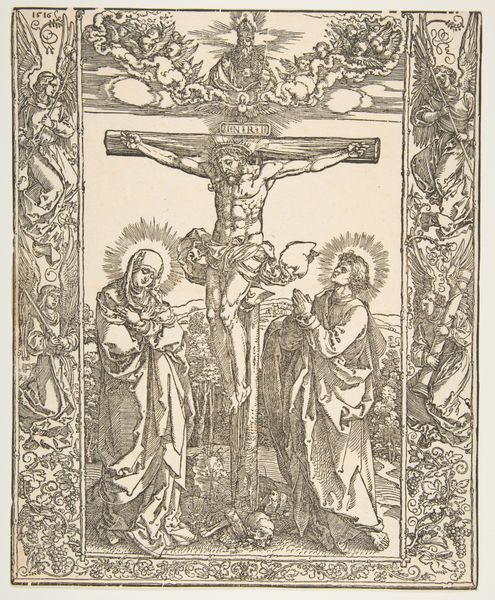

Dimensions: height 60 mm, width 40 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

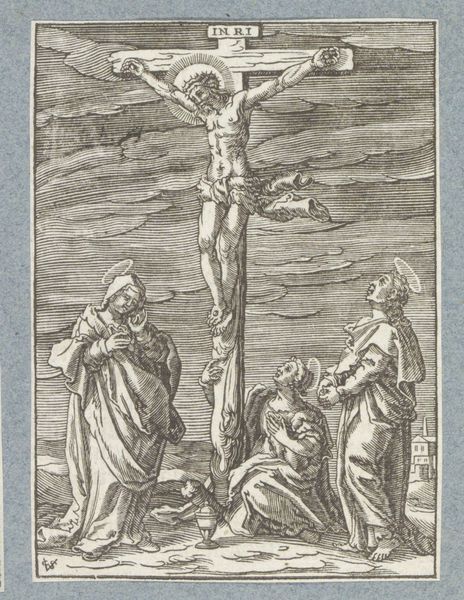

Curator: Looking at this engraving, what strikes me most is the stark, almost brutal intensity of the scene. It feels deeply personal, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Absolutely. This engraving, "Christ on the Cross, with Mary and John," dating back to the early 16th century, perhaps made between 1506 and 1538, vibrates with socio-political undertones. Altdorfer really knew how to charge his prints, his woodcuts, his little pieces, didn't he? Curator: Yes, it is powerful. It reminds me of a visceral poem. It’s so graphic and so spare at the same time. I wonder what state of mind Altdorfer was in when he created it. You know, an engraving is so deliberate, so methodical... and yet, there's such a raw energy to it. Editor: Altdorfer’s choices around the landscape speak volumes about his beliefs and the era's sensibilities. Notice how Mary and John aren't just observers but active witnesses situated in a dense, almost oppressive landscape of the souls on Earth—suggesting themes of loss, mourning, but also perseverance? It challenges us to consider the power dynamics present even in spiritual narratives. Curator: It’s such an intimate depiction, even with the traditional subject. The way he uses light and shadow... I can almost feel the grit under my fingernails, like I was standing right there on Golgotha. And, is it just me, or do the angels almost seem annoyed? Editor: Their presence, suspended between anguish and a celestial remove, can be interpreted through the lens of colonial trauma, that of forced conversion and appropriation that underpinned Christian expansion. Their stylized form highlights an awareness, a certain anxiety about the future that would demand much suffering across the globe. Curator: So, in a sense, he's layering social commentary right into the iconography of the crucifixion. It is audacious for its time. It still feels audacious. And look at those tiny figures in the background! It is if they’re bearing witness to all this suffering, trapped with Mary and John right here, under this great big symbolic weight of religious trauma and forced piety! Editor: Exactly! Altdorfer, whether he consciously intended it or not, provides an early yet critical vision of religious and social complexities that are unfortunately still applicable today. Curator: This is so powerful because, instead of simply depicting a religious moment, Altdorfer managed to ask so many uncomfortable questions. Editor: He asks us to confront our role in historical injustices through art, and that’s pretty spectacular.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.