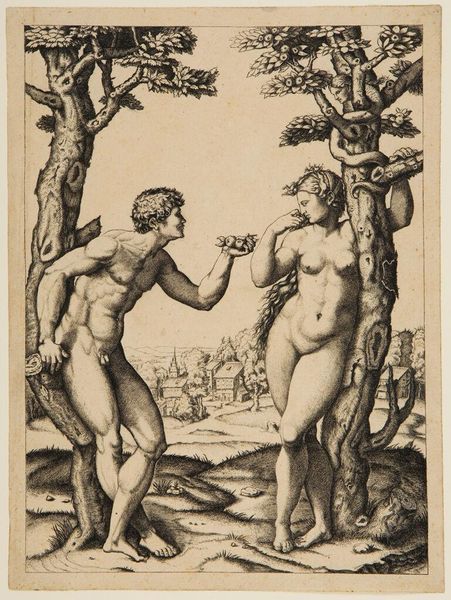

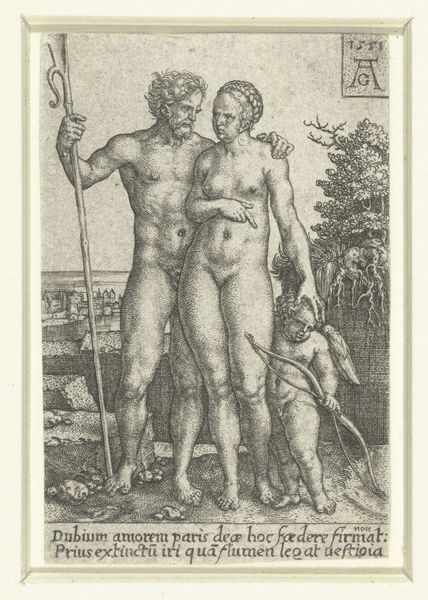

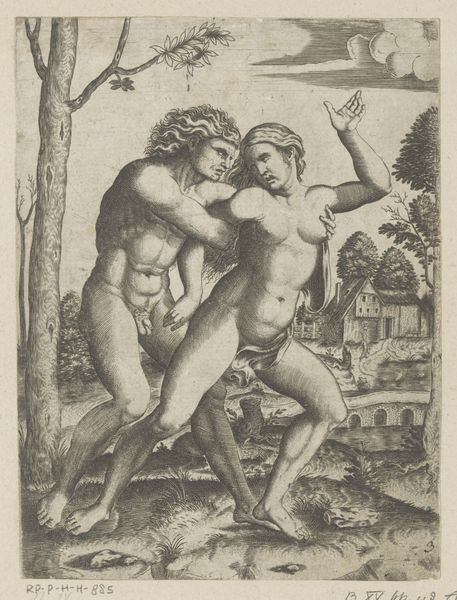

Adam and Eve flanked by two trees, a town in the background 1507 - 1517

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

tree

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

form

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: 9 1/2 x 6 15/16 in. (24.2 x 17.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately striking. There's a tension, a poised stillness that precedes a momentous decision. The texture, especially the cross-hatching, gives depth and weight. Editor: We're looking at "Adam and Eve flanked by two trees, a town in the background," an engraving executed between 1507 and 1517 by Marcantonio Raimondi. It resides in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What can you tell us about its materiality? Curator: Well, as an engraving, the image is literally etched into a metal plate, likely copper. Think of the immense labor that went into creating the dense network of lines to simulate light and shadow. It’s a reproducible medium, making the image accessible to a wider audience beyond the elite. Each print is evidence of labor. Editor: And formal elements such as line quality. Notice the precision, the variations in thickness used to define form and create volume. The contrapposto stance of both figures. It is a formal element of Renaissance art; Adam and Eve's sinuous positioning is typical. Curator: Right, and it's not just about aesthetics. Consider how these prints circulated – impacting social perceptions and knowledge of the biblical narrative. Who were the consumers of these images? How were they displayed, and what role did they play in shaping societal values or beliefs? Editor: Those Renaissance viewers would immediately pick up on how the serpentine forms emphasize tension and perhaps, that the forbidden fruit carries a potent visual meaning. It invites a slower read. Also, that Eden in a historical European setting could offer its audience an allegorical message. Curator: Definitely, but let’s think practically. An engraving like this offered a cheaper, reproducible means of disseminating the style and compositions of prominent artists. Raimondi helped broadcast artistic innovations, influencing countless other printmakers and artists beyond Rome. That accessibility changes art history. Editor: Ultimately, isn't it that precise rendering of form, the way light plays across those carefully delineated bodies, the elegant balance of the composition itself, that gives the piece its lasting power, regardless of social impact? Curator: Well, without considering the social impact, without discussing print and economy and distribution, wouldn't it be so flat to confine the message simply to what the image presents without any meaning in relation to the masses? Editor: Hmm... I see your point; my understanding deepens by appreciating those perspectives. Curator: And for me, seeing that attention to detail makes the print resonate beyond pure formalism is fascinating!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.